Independent analysis commissioned by the NHS Confederation has quantified the positive relationship between increasing NHS spending and improved health outcomes, labour productivity and economic activity.

The research from Carnall Farrar suggests that every pound invested in the NHS gives £4 back to the economy through increased productivity, demonstrating that the NHS is both an engine room for UK PLC and a security net for our local communities.

Key points

- The NHS is the fifth biggest employer globally and by far the biggest employer in the UK, with more than double the employees of the second largest employer. In many local towns and cities, the NHS is the single biggest employer and makes a vital contribution to the local economy through job creation, purchasing of services, driving demand for innovation and in keeping people healthy and well to remain in work.

- Much of the political debate surrounding the NHS tends to focus on how much it costs to run the health service, with the current annual budget at just over £150 billion and health consuming 40 per cent of spending on public services. However, very little attention is paid to part of what that investment buys: the wider economic benefits that result from investing in healthcare.

- In the run up to the Chancellor’s 2023 Budget and the next Comprehensive Spending Review, and with the government making economic growth the central plank of its reform agenda, the NHS Confederation has commissioned independent analysis to determine the link between investing in healthcare and the impact it has on a range of factors, including labour productivity, economic activity and healthcare outcomes.

- The analysis reveals:

- The economic activity of a local area, and how productive our local towns and cities are, is heavily influenced by the area’s health status. Reducing the proportion of workers off for long-term sickness increases the working population and provides a significant boost to the UK economy at a time of ongoing challenges in labour market participation, widespread labour and skills shortages and the increasing cost of living.

- The proportion of workers off due to long-term sickness is a recognised proxy measure for general morbidity, which research shows could lead to an increase of 180,000 workers among the working population; equivalent to the working-age population of Bolton.

- Further, staff employed by the NHS significantly contribute to the productivity and economic activity of local areas. However, the NHS is experiencing a record number of vacancies – currently over 130,000. An NHS that is appropriately staffed will directly increase local productivity through more people being employed in good work, enabling the NHS to collectively widen access to healthcare and reduce waiting lists. This in turn ensures that more people can return to the labour market and contribute to the economy, especially in areas of high deprivation, which have higher unemployment rates.

- Investing in health results in reduced A&E attendances and reduced long-term sickness, which are both associated with an increase in the employment rate and therefore growth in the economic activity of a local area.

- When it comes to quantifying the return on investment of spending on healthcare, the analysis reveals that every pound invested in the NHS results in around £4 back to the economy through increased gross valued added, (GVA), including through gains in productivity and workforce participation. This economic value is above and beyond the range of physical services and the intrinsic personal, societal and moral value that people receive from being able to access healthcare.

- With the UK facing major labour market and economic growth challenges, the analysis reveals the mutual and cyclical benefits of investing in the NHS and demonstrates the power of health as an investible proposition. It directly and indirectly supports our people, our places and our productivity and should be considered an essential building block of any national and local plan for growth. Given the scale of the NHS’s annual budget, this is a significant, tangible economic benefit that can be felt right across the UK. Uniquely positioned as a sector, the NHS is both an engine room for UK PLC and a security net for our local communities.

- On the back of this independent analysis, NHS leaders encourage the government to place investment in health at the heart of the reform agenda for economic growth. At minimum, this will require the government to protect the NHS budget, which will mean making up the shortfall in funding that has been lost due to the impact of soaring inflation (the NHS is facing a minimum real-terms cut in funding of £4 billion this year). In the medium-to-long term, this will require governments of all persuasions to commit to maintaining NHS investment at the long-term historical average and avoid lengthy periods of underfunding, such as occurred during the decade of austerity in the 2010s, which have left the NHS with 130,000 vacancies and a crumbling estate.

Background

Not only has UK productivity, the main driver of long-term growth and living standards, lagged behind that of many OECD countries since the 2008 financial crash, but there remain significant regional disparities across the UK. For example, many parts of the midlands and the north of England are now among the poorest in Europe. This low productivity manifests itself in poor infrastructure, health and educational standards, as well as other indicators of social cohesion such as increased child poverty, reduced life expectancy and rising crime rates.

While the response to the pandemic in 2020 was national in scope, the underlying fragilities within our communities further exacerbated this economic and social divide. This posed new and significant challenges for policymakers across a range of connected areas, perhaps most notably in relation to our labour markets – the traditional heartbeat of a thriving, prosperous economy and the lifeblood of the NHS seeking to address growing backlogs for care.

As the membership body for the full range of healthcare organisations, the NHS Confederation has long believed that the health sector has a central part to play in both strengthening our economic foundations and building our economic resilience. While attention understandably tends to focus on the quality and quantity of service provision returned for the level of public investment made in the NHS, the impact of the health service on everyday life stretches far beyond its immediate operational activity. However, this wider impact is often little understood, raising questions over the NHS’s economic value at the very time our economy is in most need.

It was for this reason we partnered with Carnall Farrar to quantify the positive relationship between increasing NHS spending, health outcomes and economic activity – the first nationally modelled attempt at such a distinction. While we believe such analysis is important generally, given the need to design policy interventions that positively support communities, we think it is particularly vital that this relationship is better understood at the current stage in the economic and political cycle.

health ... and the economy are directly, mutually and intrinsically linked

The analysis shows how health – predominantly funded through the NHS – and the economy are directly, mutually and intrinsically linked. A plan for investment that is broad and ambitious can narrow health inequalities, return people to the labour market and unlock some of the critical bottlenecks holding back economic growth.

This report explores the main findings from Carnall Farrar’s detailed analysis of the link between investing in health and economic growth. We believe that the report, and the findings within it, show clearly that health should be central to any governmental plans for the economy. The detail, methodology and conclusions will be of interest to national policymakers debating our future economic course, for local economic leaders determining a more productive place, and for integrated care system and health service leaders delivering ways to improve population health.

Methodology

We worked with the health analytics team at Carnall Farrar to quantify the relationship between increasing NHS spending, health outcomes and economic activity.

To measure economic activity, we focused on gross value added (GVA), which measures the contribution made to an economy by one individual producer, industry, sector or region. We assembled a comprehensive longitudinal dataset of NHS spend, population health needs, health and care activity, and economic activity.

To account for geographical differences, data was collected at International Territorial Level 3 (ITL3 – counties, unitary authorities or districts in England) and we investigated how impacts vary with deprivation.

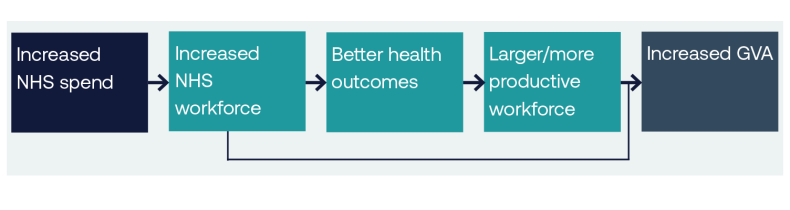

The statistically significant link between NHS spend and GVA was calculated using both a fixed effects regression model and a propensity score matching approach. We also hypothesised on the underlying mechanisms of the relationship, including:

- increasing NHS spend increases NHS workforce, which in turn creates access to healthcare provision

- increasing access to GPs is associated with a decrease in A&E attendances and long-stay non-elective inpatient activity

- decreasing both A&E attendances and long-term sickness is associated with an increase in the employment rate and therefore growth in GVA of an area

- increasing NHS workforce, which contributes significantly to an area’s GVA especially in areas of high deprivation that have fewer high-GVA jobs.

Logic chain on the relationship between increased NHS spend and increased GVA

For historical reasons, there is a limited evidence base for understanding the relative economic benefits of investing in the NHS. This partly relates to the nature of the NHS’s standalone budget, which is passed directly from the Treasury to the Department of Health and Social Care to be spent on agreed health service provision. Partly though, it is also because while the NHS is expected to spend its money wisely and achieve regular efficiency targets, it has not been seen as an investment by those responsible for growing the economy. As the health service budget increases in a tight fiscal envelope, this is likely to change.

For this report we restricted our analysis to considering trends close to currently observed behaviour. Our ability to fully understand the causal relationships between these measures is limited by data availability, and the number of confounding effects we can account for.

Nevertheless, we believe we present a compelling argument for continued, and indeed increased, investment in the NHS.

Proving the link to economic growth

Carnall Farrar’s analysis, conducted in summer 2022, reveals four headline findings:

- A significant and associated link between NHS spend and gross value added (GVA), with a £4 increase in GVA per head for each £1 NHS spend per head, for a needs-weighed population.

- Increasing NHS spend increases the NHS workforce, which in turn creates access to healthcare provision.

- Decreasing both A&E attendances and long-term sickness is associated with an increase in the employment rate and therefore growth in GVA of an area.

- Increasing the NHS workforce directly contributes significantly to an area’s GVA, especially in areas of high deprivation which have fewer high-GVA jobs.

This work to articulate the direct link between spending on health and the wider economy is nationally significant in the context of the funding that we already dedicate. The Department of Health and Social Care’s budget is expected to increase from £152.5 billion to £182.9 billion in 2024/25. We have not been alone in making clear and persuasive arguments about how increased investment in the NHS improves access, fairness, quality, safety, innovation, and the overall ability to deliver the healthcare needed by every person in this country from cradle to grave. However, it also reveals that this planned increase in budget is not only vital for services, but should be seen as an investment opportunity by and for others too, particularly in the face of threats to the funding available as a result of inflation or competing priorities.

The NHS in the UK is tax-funded, with the direct interrelations between it being sustainably resourced and a well-performing economy being clear. What our analysis shows, if there were any existing doubt, is that this relationship is two way. The work looks at some of the key mechanisms that investment in health supports participation and productivity in the UK labour market and progressively addresses inequalities in our communities.

Supporting the labour market

Nowhere is the two-way relationship more evident than in the changing labour markets. This is particularly relevant with 2.5 million people currently off work in the UK (July 2022) due to long-term sickness. As this report and numerous others show, economic activity in a location is strongly influenced by the area’s health status.

The proportion of workers off due to long-term sickness is itself a recognised proxy measure for general morbidity. Our research shows that a 1 per cent decrease in the general morbidity, measured via the proportion of workers off due to long-term sickness, is associated with a 0.45 per cent increase in employment rate, equivalent to an extra 180,000 workers amongst the UK working population, or the working age population of Bolton. This decrease is also likely to increase median hourly pay by £0.47, leading to a productivity increase among workers across the breadth of the wider economy.

By increasing this employment rate by 1 per cent through, for example, improved NHS access, we would be adding to an area’s GVA by £292 per head – a significant boost to the economy at a time of ongoing challenges in labour market participation, widespread labour and skills shortages and the increasing cost of living.

An NHS that is appropriately staffed will directly increase local GVA

Going further, the NHS is itself the largest employer in every local economic geography, with NHS workforce expenses contributing up to 8 per cent of an area’s GVA, yet the service is currently experiencing a record number of vacancies. An NHS that is appropriately staffed will directly increase local GVA through more people being employed in good work. This in turn enables the service to collectively widen access to healthcare and reduce waiting lists, thus ensuring more people can return to the labour market and contribute to the economy. This is a very clear example of the mutual and cyclical benefit of investing in the NHS.

A significant regional impact

While this report represents a clear national overview of the role of the NHS in economic growth, we expect the strength and nature of these relationships to vary between geographic regions, mainly due to differences in characteristics, such as working-age population and deprivation.

One of the significant economic strengths of the NHS is that it is everywhere. It plays an important, varied and active role in urban, metropolitan and rural economies. Its value may change depending on the local context, yet our analysis demonstrates a correlation between the level of deprivation in an area and the contribution of NHS spend on workforce expenses to the local economy. So, investment in the NHS has progressive real-term and real-time implications for local areas.

Understanding system productivity

With an increased budget comes increased expectations. To be seen by others as an investment, it is important that the NHS itself acts like one. As well as our supporting role in wider economic and social development, we must ensure we are organising and allocating our own resources effectively and with broader outcomes in mind.

A more in-depth analytical look at how we might do this could have important implications for future health policy. As a starting point, our analysis looks at one mechanism for greater system-wide productivity: access to primary care. The findings show that the ability of primary care to support interventions in population health management provide an opportunity to create higher returns on NHS spend investment. For example, investing in the number of GPs per head leads to reductions in both A&E attendances and long-term sickness, which are associated with an increase in the employment rate and growth in the economic activity of a local area.

The analysis specifically finds that the impact of adding one GP for 10,000 people equates to an estimated reduction in cost to be £82,071, relative to need. This is directly linked to an improvement in the population's health and the monetary impact is likely to be significantly greater than this direct saving, given wider benefits.

Future analysis to support and evolve this thinking could be focused on whether other areas of health-and-care-related spending can have similar impacts on productivity in targeted sectors, such as with mental and community health or social care, or in certain kinds of spending, such as with capital spending or digital infrastructure.

Fit for a changing economy

The timing of this report is particularly important. The changing focus on the economy can be told in two separate government reports published just eight months apart. The levelling up white paper, published in February 2022, focused on the inequalities that exist in this country, including how to support those parts of the UK that have not shared equally in economic success. It sought to:

‘…realise the potential of every place and every person across the UK, building on their unique strengths, spreading opportunities for individuals and businesses, and celebrating every single city, town and village’s culture. This will make the economy stronger, more equal and more resilient, and lengthen and improve people’s lives.’

In October of the same year, the UK government, under a new administration, published the Growth Plan 2022, which took a more explicit position on the economy and made growth the government’s central economic mission. It stated that:

‘Boosting productivity growth and labour supply is central to raising the UK’s economic growth. The supply-side reforms are at the centre of the government’s Growth Plan and represent an ambitious first step towards achieving 2.5 per cent trend growth in GDP.’

The policy pendulum between stimulating and spreading economic growth is constantly shifting, though in practice both will remain vital for our prosperity and prospects. If there is one overriding message from our collective experiences since March 2020, it is that while the NHS is at its heart a moral and social service, it is also an economic one.

As the economy evolves, the NHS should be considered a worthwhile investment, acting as a safety net of course, but also as a springboard for growth

As one of the key anchors in every local economy, the health service’s size, workforce, procurement budget, environmental impact, industrial stimulant and general economic, social and civic influencing power have been at the heart of national and local economic recovery planning. As the economy evolves, the NHS should be considered a worthwhile investment, acting as a safety net of course, but also as a springboard for growth.

Realising the economic potential of the NHS - immediate lessons for policy makers

The findings in this report will be of interest for a host of leaders and organisations, both nationally and locally. We have highlighted the headline lessons below:

National government

- The NHS should have a clear and direct role in government plans to both scale and spread economic growth across the UK, with the relationship between health and productivity being at the heart of national decision-making.

- An immediate national priority should be to invest in expanding NHS recruitment to widen access to healthcare provision, which will help address low participation in the labour market.

Mayoral combined authorities and local economic leaders

- Population health has been shown to be a key driver in narrowing long-standing regional variations in productivity and should be considered a priority in spatial economic strategies, including devolution deals.

- Given the strength and nature of the impact of NHS investment varies between geographic regions, further work should be undertaken to understand local implications and approaches to shared decision-making.

Integrated care systems and the NHS

- There are wider economic benefits to be derived from assessing and understanding allocations of NHS expenditure, including between primary and secondary care, which should be considered by system leaders.

- The fourth ICS purpose of helping the NHS support broader and economic development is an important development in improving outcomes for populations and new metrics for showing its value should be prioritised.

Maturing our return on investment

We believe this report marks the start of unearthing the power of health as an investible proposition. While the NHS is routinely measured on a large number of metrics, its economic return on investment is not presently considered one of those. This report shows the value of undertaking this form of analysis on a more sustained basis, both for the NHS reputationally in supporting a greater understanding of the wider impact it can have, and for local non-NHS leaders seeking to maximise the service’s broader economic and social value. As a service the NHS should be striving to know more about the routes through which it can create value and where it can have the greatest impact on health outcomes at the same time as creating and spreading economic growth.

Over time and building on the early work undertaken by the NHS Confederation and Carnall Farrar, we strongly believe a more in-depth, nuanced and rigorous process can be developed which is recognised and respected by government, partners and the range of think-tanks.

Viewpoint

As this report shows, the money invested in our health service is exactly that: an investment. It directly and indirectly supports our people, our places and our productivity and should be considered an essential building block of any national and local plan for growth. What is most notable about the findings is the size of the multiplier effect. For every pound invested in the NHS, it gives around £4 back to the economy through increased productivity. This is, of course, on top of the sheer range of services the NHS is funded to provide.

Although this is a first step in understanding the impact of investing in health on the wider economy, we can strongly conclude that our current funding in the NHS can be seen as sound investment in the future of country and be placed at the heart of the reform agenda for economic growth. It follows that the government should urgently review the eroding impact of soaring inflation levels on the value of the NHS budget in order to, at minimum, maintain the level of real-terms spend on care.

If we were to maximise the impact of this key driver of growth and relief from an embattled labour market, we should also consider a return to the long-term historical average real-terms funding levels for the NHS. By avoiding the long periods of under-investment seen in the last decade, we might have been able to avoid the current significant staffing gaps in the service and country, and already have been on a stronger journey to growth.

Given the scale of the challenges we are facing and the power of NHS’s budget, we propose that these findings are significant, demonstrating a tangible economic benefit and potential that can be felt right across the UK. Uniquely positioned as a sector, the NHS is both an engine room for UK PLC and a security net for our local communities.

Our Health Economic Partnerships work programme supports the NHS to understand its growing role in the local economy and to develop anchor strategies at institutional, place and system level. For more information go to our health economics partnerships web pages or contact Michael.Wood@nhsconfed.org for more information.