Key points

Health and care systems are under significant pressure. System improvement can help deliver more holistic, place-based care that improves people’s health and expands beyond the confines of the NHS to include the voluntary sector, local government and other partners. It provides an opportunity to do things differently by working at scale, actively breaking down siloes, maximising resources and tackling issues that cannot be solved by individual organisations – harnessing improvement methodologies.

We build on our earlier research, Improving Health and Care at Scale, with the insights from the 2024 Learning and Improving Across Systems peer learning programme. The programme was delivered in partnership by the NHS Confederation, the Health Foundation and the Q Community. It brought together 168 leaders from across 38 integrated care systems, NHS trusts and health boards, local authorities and voluntary organisations across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Programme participants spoke about several challenges that stifled progress in system improvement, including fragmentation and siloed working, financial constraints, and lack of senior leadership support. These challenges, alongside the reality that the complexity of system change means that progress may take time, can take its toll on the individuals leading system improvement efforts.

Peer learning supports system improvement by nurturing a sense of belonging and providing peer support, reducing the sense of isolation. It enables leaders to share experiences and challenges, facilitating knowledge sharing and benchmarking, through helping them learn from other systems. Additionally, peer learning can help support effective and trusting relationships, a crucial element of effective system improvement to improve quality of care and patient outcomes.

System leaders should consider strengthening peer learning mechanisms and enhancing leadership and governance for system improvement. Central bodies should develop and promote a shared approach to system improvement, and support peer learning programmes and networks at a national scale.

Background

Health and care systems are at a crossroads. They are facing increased demand due to an ageing population, widening health inequalities and immediate pressures on access to general practice and waiting times for elective care – within a constrained financial environment. There is a huge need to drive change and transform health and care to deliver better patient outcomes, improve population health and make the system sustainable. The planned merger of NHS England into the Department of Health and Social Care and cuts to both integrated care boards (ICBs) and providers must be managed carefully to ensure government ambitions are not brought to a standstill.

In England, the upcoming ten-year health plan will set out the future direction of travel, structured around three shifts: hospital to community, analogue to digital, and treatment to prevention. Integrated care systems (ICSs) will be at the heart of implementing its vision and must use all the tools at their disposal to make the radical shifts needed.

At Q and the NHS Confederation, we believe that large-scale change in health and care will happen through leaders across multiple organisations, sectors and localities coming together to intentionally plan, collaborate and deliver work holistically. Improvement approaches are the heart of this and are a key way to ensure change is sustainable and long-lasting. [1] In fact, the Hewitt review set out the ambition for ICSs to become ‘self-improving systems’ – combining high levels of autonomy and accountability to deliver on their strategies collectively and improve the quality of patient care and outcomes. [2]

System improvement aims to deliver more holistic, place-based care that expands beyond the confines of the NHS to include the voluntary sector, local government and other partners supporting health and wellbeing for individuals and communities. System improvement is about intentionally working across multiple organisations, different sectors and geographies to create the conditions and change required to improve health outcomes for the population. This complex work can be hard to navigate, so requires different improvement, transformation and innovation methods, used at different levels to enable and deliver large-scale change effectively.

Previous research commissioned by the NHS Confederation, Health Foundation and Q community demonstrated the variety of approaches of ICSs at the forefront of this work. [3] It showed encouraging examples of how leaders were convening their systems around improvement, establishing new learning communities and starting to deliver collaboratively on national and local priorities.

This report aims to provide insights into some of the key challenges facing those leading and delivering improvement across systems and how peer learning can facilitate progress in this space.

The report draws on insights from Learning and Improving Across Systems peer learning programme, delivered in partnership by the NHS Confederation, the Health Foundation and the Q community. This includes evaluation and insights gathered throughout the programme by the partnership team, and the independent evaluation provided by Ashworth Research. [4] All quotes included in this report are from programme participants and have been anonymised.

About the Learning and Improving Across Systems peer learning programme

The NHS Confederation, the Health Foundation and the Q community are working in partnership to support leaders in creating the context and conditions for change. In 2024, we delivered the first year of the Learning and Improving Across Systems peer learning programme.

We designed the programme to:

- build greater understanding of improving across systems

- increase awareness and confidence to use different improvement frameworks, tools and approaches

- facilitate peer connections for learning and support.

The nine-month programme was delivered online, through four workshops and four peer coaching sessions, and involved a mix of tools, expert talks and peer discussions centred around personal inquiry questions. The programme was structured around the Cross-System Improvement Framework that supports leaders in creating the conditions and delivering large-scale health and care improvements across systems.

We brought together 168 leaders across 38 integrated care systems, NHS trusts and health boards, local authorities and voluntary organisations across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The roles included directors of improvement, quality improvement leads, system transformation managers, clinical directors and non-executive directors. Over a third of registered participants were active members of the Q community, a community for people working to improve health and care across the UK and Ireland. The programme supported leaders’ professional development and created new connections across systems.

What are the key challenges for progressing system improvement?

The leaders who joined the peer learning programme envisioned system improvement as being able to “unlock the potential” to improve population outcomes, through overcoming boundaries and silos, more joined-up thinking and integrated working, reducing duplication and variation, and enabling effective adoption, spread and scale.

Our previous report identified some of the challenges to progressing this work. This included lack of headspace and capacity, a legacy of top-down management in the NHS and the need to develop new skills and capabilities. [5] Our engagement through the peer learning programme provided additional insights into some of the key challenges to system improvement, across a wider range of areas across the UK.

Fragmentation and siloes

Participants reflected on the challenges of fragmentation and siloed working. System improvement is being led by people from a range of different backgrounds and who occupy a broad range of roles, as evident by the wide spectrum of job titles among programme participants.

Specific challenges arising from this context include a lack of shared understanding of ‘system’ and ‘system improvement’ among partners, particularly across different sectors. As one participant reflected:

"System means very different things depending on your perspective and experience. ”

The differences in language and understanding presented a barrier to effective partnership working, emphasised further by the language of improvement itself being perceived as jargonistic and unclear by stakeholders.

"A key challenge is inclusive language around improvement that allows others to be involved."

The difficulties of coordinating and delivering improvement work across organisational boundaries was a key theme across the programme. Participants reported duplication of efforts, partly due to lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities. We also heard reflections from participants on how organisations are often reverting to their self-interest. These experiences resonate with the ‘club and country challenge’ articulated in our previous report, where leaders spoke about being confronted with the tensions between priorities of their own organisation and priorities of the system as a whole – posing a risk that systems descend into conflict and stasis. [6]

This fragmentation is underpinned by misaligned financial incentives which drive behaviour and decision-making across system partners. Raised by the Hewitt review as a barrier to integration, there is hope the ten-year health plan will address this issue, but it is continuing to be a challenge for delivering improvement collaboratively. [7] This challenge is exacerbated by the need to deliver in-year savings when the impact of improvement programmes is more long term. The NHS Confederation has been working with its members to put forward different payment mechanisms that support, rather than hinder, integration and collaboration. [8]

Financial constraints and competing priorities

Participants mentioned the pressure to achieve financial efficiencies and budget constraints as a major barrier to delivering system improvement. This reflected concerns across the sector. For instance, responding to a survey in spring 2024, ICS leaders were concerned that financial challenges in the NHS and local government would impact their ability to deliver on their ambitions and negatively impact partnership working. [9]

Financial constraints also shaped the capacity dedicated to improvement – with variation across systems and organisations, and dependent on the context and leadership in place. Contributing to system improvement often relied on people’s initiative and goodwill, which is tested during periods of financial and operational pressure. Participants indicated that previous levels of operational flexibility diminished when funding became tighter, making it difficult to allocate time and resources toward quality improvement projects.

"The simple impact of budgets being slashed across the board … so, the ability or the leeway that people had previously to do things and just get stuff done has gone, because there has been such a stringent financial focus that it means the level of flexibility has deteriorated."

The pressures of financial constraints were made worse by the need for ICBs to reduce their running cost allowance by 30 per cent by 2025/26. [10] The ensuing restructures created instability and uncertainty among staff, although in some cases, it did result in more resource being allocated to improvement. The announced further 50 per cent reduction in ICBs running and programme costs for 2025/26 is likely to have a further impact on the role of the ICB to deliver improvement.

In this context, programme participants were grappling with how to demonstrate that system improvement can address key operational pressures and contribute to increased productivity and efficiency. Improvement efforts often need to demonstrate cost-effectiveness to gain traction, and it can be difficult to prioritise long-term transformation work.

“How do you create a culture of improvement in the face of constant firefighting, both operationally and financially?"

Lack of senior buy-in and support for system improvement

Working in system improvement means finding innovative and creative ways to get buy-in from partners and highlighting how it can address local and national priorities. Participants identified endorsement from senior leadership as essential to do this, as this helped demonstrate the role and potential that system improvement can play and the need to prioritise it. In the absence of leadership support, system improvement progress is challenging.

“The board at our trust wasn’t really bought into quality improvement, and it wasn’t being led from the board ... So, we’ve had this senior leadership board involvement bit of the puzzle missing."

To tackle some of the fragmentation described previously, senior leaders across the NHS, local government, ICBs and integrated care partnerships (ICPs) have a role in creating momentum and strategic direction for improvement, through practising effective system leadership. [11] Yet, participants raised variation in knowledge, skills and awareness of improvement at the leadership level as a recurring concern.

“Influencing without direct authority is a challenge. Sometimes it’s about helping leadership see the long-term benefits rather than just short-term gains."

Through the programme, participants explored influencing techniques which helped them work through resistance to change and how to address misaligned priorities. [12] The case studies included in our previous report also demonstrate the key role ICS leaders in particular can play in galvanizing improvement. [13]

The complexity of system change and the challenges described above mean that progress may take time. Peer learning is an approach that can help us realise the benefits and opportunities of system improvement and ensure learning is shared throughout the journey to becoming ‘self-improving systems’.

How can peer learning support progressing system improvement?

Peer learning is a well-established practice in the public sector, offering significant benefits throughout the different career stages. At its core, peer learning involves individuals learning with and from each other by sharing ideas, experiences and challenges. This approach is prevalent and highly regarded in quality improvement and has long been a central focus of the Q community’s efforts.

Peer learning is particularly well suited to applied, pragmatic learning in complex settings. Our research previously identified peer-to-peer learning within and across ICSs as a crucial enabler of system improvement. [14] Insight from the programme highlights three specific aspects of peer learning that supported leaders in progressing system improvement: peer support and connection; practical learning from each other; and relationship building.

Peer support and connection

We heard throughout the programme that participants felt lonely and isolated in their roles, regardless of their level of seniority. This sense of isolation and lack of organisational or system support, together with the challenges mentioned above, meant that many of the participants were struggling to meet their aims. Peer learning opportunities bring together people in similar roles (in this case, people working in improvement at a system level), which can positively impact people’s morale.

“I do think just that connection with other people within improvement is interesting because maybe you don’t realise quite how isolated you are, and actually it does make quite a difference.”

Peer learning opportunities can provide a sense of solace that comes from shared experience and navigating uncertainty together. Throughout our programme, we heard positive reactions to shared challenges. Participants shared that hearing about challenges that peers were experiencing in other systems felt “cathartic” and helped create a sense of camaraderie that people were not “the only one” navigating specific difficulties and struggling to progress at a desired pace. In turn, this offered reassurance and supported participants’ confidence in their system improvement work.

“I think it was perversely encouraging … even people who’d been in those roles a lot longer were still struggling with some of the same issues. You should know yourself that Rome isn’t built in a day, but sometimes it’s just helpful to understand that."

Participants also valued finding out about what specific areas their peers were currently working on. Within our programme, participants would share their personal inquiry questions and reported on their progress. The questions ranged from focusing on managing complexity to partnership working. We repeatedly heard from participants that the range of their peers’ questions highly resonated and felt “oddly reassuring". It became apparent that different parts of the system were trying to solve similar problems, which helped some participants feel validated and reassured. This helped break down perceived siloes and increased participants’ motivation and confidence that they were on the right track.

"Listening to people across the country, and where they were up to, was helpful. ... having that shared experience was helpful, because I think it can be quite isolating ... trying to do something that’s difficult..."

Learning from each other

Peer learning offers valuable opportunities for knowledge sharing and building. Peer learning is especially valuable because at present, there are scarce examples of good system improvement practice in published materials due to the early stage of the work and challenge of capturing impact. The informal sharing between peers can help build an evidence base for system improvement and increase its credibility, which is essential for enabling progress.

Through learning about progress from other systems, participants were able to develop a clearer understanding of what forms system improvement can take. They were able to benchmark their own systems against others. This helped many participants realise their existing strengths, reassuring them that they were not as far behind as they had previously thought.

"I naively went in thinking that we were really far behind, and that we had a lot of catching up to do, but I think everyone’s on a par but doing slightly different things."

Learning from the examples of more advanced systems was ” another valuable aspect of peer learning. Using the Cross-System Improvement Framework as a reflection tool, participants shared concrete examples of their activities. [15] These ranged from forming partnerships with organisations beyond healthcare to setting up learning systems.

"I’ve learnt from other people’s experience about what works well, what doesn’t … there’s been a lot of thinking that’s gone on ... it’s been good to get other people’s perspectives around different types of problems, or similar things that they’re facing, and how they’ve approached it."

Peer coaching and direct input and feedback added further value to the peer learning experience. This form of peer-to-peer support complemented the general sharing of experiential knowledge and was particularly effective for many programme participants in advancing system improvement.

Relationship building

While building effective and trusting relationships is a key aspect of any peer learning, these experiences can also support relationship building within and beyond participants’ own organisations and systems. Several programme participants mentioned that the peer learning experience emphasised to them the importance of relationships as a prerequisite for leveraging change at the system level. In fact, we have identified building relationships and trust as one of the five principles of delivering system-level improvement approaches. [16]

"It’s made me recognise the importance of those connections across systems … It’s the networking – just meeting other people has made me realise that that’s what I need to do, but within my ICS."

Effective relationship building across different roles, organisations and sectors is underpinned by a shared understanding of system-wide improvement approaches. A shared focus on system improvement can, in turn, also provide the grounding focus and purpose for these relationships, helping to mitigate fragmented and siloed working.

Learning with and from peers from different parts of the system, as well as different countries (that is, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) encouraged programme participants to consider power dynamics and different ways of working that are at play, including around the sharing of resources.

Organisations rarely come together on an equal footing: there are different resources, commitments and priorities that need to be considered (for further considerations on how these can effect partnerships, see the Leading Successful Partnerships guide). [17] Developing shared working principles and clarifying roles, for example through “playbooks” and “concordats”, helped programme participants better work together with partners across the system. One participant shared an example of how their voluntary sector partner led on the development of a shared concordat:

"VCSE [voluntary, community and social enterprise] led on development of a ‘concordat’ on how we work together as a system – a set of behaviours and values underpinned by possible ways of holding each other accountable."

Our insight from the peer learning programme also highlighted the importance of taking an adaptive and inclusive approach to the tools and methods in system improvement. The Cross-System Improvement Framework, [18] which we used as a tool for reflection and planning, provides one such option. With the emphasis on ‘creating the conditions’ and ‘delivering transformation’, it highlights the main aspects that need to be considered without being overly prescriptive or tied too closely to one specific sector at the expense of excluding others.

Several participants thought this framework was particularly valuable because it was not NHS or health-centric and thus more amenable to sharing with partners outside healthcare. Adopting shared tools and methodological approaches, alongside taking a broad and inclusive approach that values diverse strengths and experiences from different partners, can further support systems to navigate the challenges of fragmented working.

Spotlight: Learning from what works – and what doesn’t

Alex Baldwin is the director of operations for the Future Systems Programme, an initiative dedicated to designing and constructing a new hospital in Bury St Edmunds. His role includes preparing for the new hospital’s operational launch, ensuring that the hospital is equipped to deliver effective and integrated healthcare services.

Alex spoke about the valuable role of peer learning, which enabled him to expand their network and learn from other systems.

“I’ve learnt from other people’s experience about what works well and what doesn’t. There’s been a lot of thinking that’s gone on, in terms of some of our appreciative inquiry, and how that’s helped me think about approaches, or challenges and issues that I’m facing."

Alex found the programme beneficial to his current initiative on improving blood test services – testing how hospital-based phlebotomy service can be extended to appointments in patients’ locality through GPs and community settings. Improved system working would eventually mean that people do not need to come to hospital for a blood test. Alex reflected that given the complexity of healthcare systems, it is hard for a programme like Learning and Improving Across Systems to have immediate system impact – but noted that it did facilitate a process of “nudging people into the right space.”

Spotlight: Improvement is a shared endeavour

Kathryn Hall is the associate director of One Gloucestershire Improvement Community, Gloucestershire ICS and an active Q member. She works collectively with the hospital trust and the mental health and community trust and primary care, social care and partners in the VCSE sector. Kathryn joined the peer learning programme as she wanted to meet others on the same journey.

“I was interested to find out how other people were looking at it from larger systems, systems of different geographies and organisational politics going on. It can be a bit lonely working in an emerging field, so I was hoping to meet some people but also be a part of giving something back as well."

Kathryn’s personal inquiry question was how to convene colleagues to collaborate and co-design the next phase of their system improvement strategy. She reflected on how the programme helped emphasise that it is everyone’s role to make improvement work. This realisation has facilitated her to include more people into the improvement dialogue. Kathryn highlighted that hearing diverse perspectives from other peers on the programme was important in enabling her to consider how to build relationships within her own context, providing her with confidence and validation for her approaches and hence greater resilience for system improvement.

“I probably enjoyed the peer coaching sessions the most. There would be some people there who were looking at a big pathway – system-wide transformation. There would be people there considering how they got continuous improvement in their organisation right. People who are thinking from an innovation perspective. People in enabling roles. … That enabled me to think about, ‘How might I build those relationships within my own system?’ The impact of the peer coaching element has given me a sense of confidence that this is a real thing – it’s given some credibility, some tangibility, some depth and texture to understanding the whole variety of different people involved in it nationally.”

Spotlight: Increasing confidence, deepening understanding and making connections

Hannah Parker is the improvement business partner at the Humber and North Yorkshire ICB and recently joined the Q community. She started her current role shortly before joining the Learning and Improving Across Systems peer learning programme. This was her first position at an ICB, having previously worked in improvement lead roles at several different NHS trusts.

Hannah experienced a range of outcomes from participating in the programme, including increased confidence, learning from a diverse set of peers, enhancing her understanding on the breadth of different approaches being adopted within system improvement and making new connections. The programme helped her benchmark her own system against others, realising that they were not as far behind as she had previously thought.

“I went in worrying we were really far behind, and that we had a lot of catching up to do. I was really keen to find out what other systems were doing, how they were approaching improvement. It was fascinating learning about all the different approaches being taken and how teams have started out.”

Conclusion and recommendations

System-level improvement is key to delivering the government’s ten-year health plan and transforming health and care systems for the future. Health and care leaders are ambitious about its potential to drive change in complex systems. In a challenging environment, strengthening peer learning is an opportunity to ensure those leading the change have the connections, support, tools and knowledge needed to do this.

To support system improvement, system leaders should consider:

- Strengthening and embedding peer learning mechanisms and processes. Insight from our peer learning programme highlights the importance of building in time for reflection and providing a structured approach for effective sharing and relationship building.

- Enhancing leadership and governance for system improvement. Supporting capability and understanding of improvement among senior leadership is key to unlocking further change. This could include training and development for senior staff and supporting frontline staff with protected space to innovate and to implement new ideas.

Wider changes are needed to fulfil the ambitions of self-improving systems. Central bodies have a key role to play in facilitating and supporting this work. They should consider:

- Developing and promoting a shared approach to system improvement. This could include encouraging the adoption of shared improvement principles while valuing diverse methods and perspectives, strategically building relationships, and supporting a common approach to measuring impact that considers working across organisations in a complex system.

- Supporting peer learning programmes and networks at a national scale, to enable learning across different systems and countries. Facilitate opportunities to share emerging learning and case studies on enablers of system improvement, to help build resilience and sustain energy.

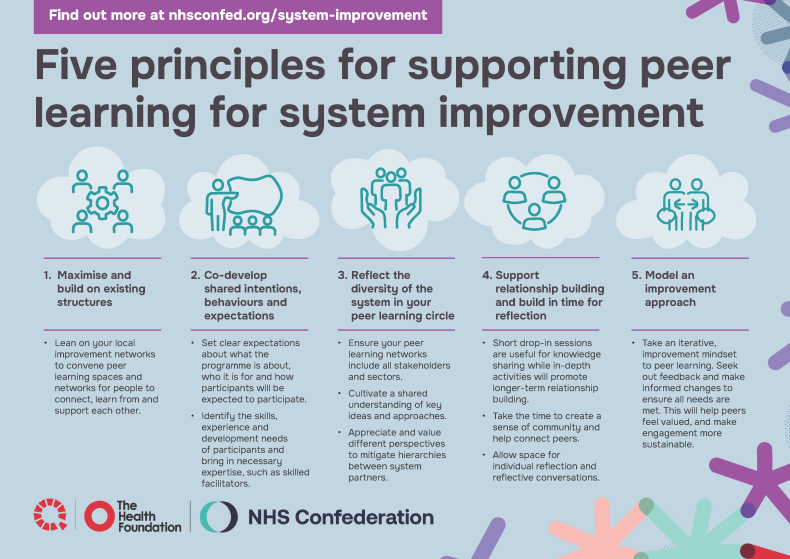

Peer learning can support leaders to progress system improvement by providing peer support and connection, enabling practice learning and building relationships across sectors and systems. Here are five key principles for supporting peer learning.