Are integrated care systems improving population health outcomes?

A four-part series exploring how integrated care systems are faring against their core purposes. In this edition, we delve into how systems are improving population health outcomes.

When integrated care systems (ICSs) were established in 2022, they were under no illusions about the scale of the task ahead of them – or the reasons for their existence. Still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, the NHS and social care system faced the most challenging time since their creation, and a deterioration in the nation’s health.

ICSs’ North Star, often known as their four core purposes, focused early efforts, and in the summer of 2022 a renewed energy and sense of optimism was palpable. Yet more than two challenging years on, how are systems faring against their strategic missions?

"We have brilliant examples of where we have transformed the process of discharge from hospitals, and where community interventions have helped people to be treated closer to home,” remarks Dr Kathy McLean, who chairs two integrated care boards (ICBs) in the East Midlands and the NHS Confederation’s ICS Network. “ICBs, working collaboratively, are transforming services and improving prevention. But we can’t create these innovations in isolation,” she says.

“It is only by working together – differently – that we will be able to ensure residents get the best from their health and care service.”

Working together differently has been the ‘secret sauce’ behind notable improvements in health in Bedford, Birmingham and Solihull, and Surrey, and will be vital in contending with projected patterns of illness in England over the next two decades.

Keeping residents warm in Bedford

In Bedford, analysis of population health data by a joint council/NHS data unit identified almost 2,000 patients with pre-existing health conditions who were especially vulnerable to rising energy costs.

“Every time the temperature drops by 1 degree below five degrees centigrade, we see an increase of about 20 per cent in GP consultations for respiratory diseases,” says Ian Brown, chief public health officer at Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes (BLMK) ICB.

“It was really clear when we saw that data, when we saw the impact price hikes were having on our population that we needed to do something about it.”

The result was the Warm Homes Bedford Borough project. Funded by Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes (BLMK) ICB, commissioned by Bedford Borough Council and run by the National Energy Foundation’s warmth and wellbeing service, Better Housing Better Health, it was designed to help support these households.

Over 1,600 patients whose GP records showed they were at risk of fuel poverty and had a chronic health condition which could worsen by living in a cold or damp home, were invited to take part.

Three-quarters of the residents, who went on to receive support from the scheme, said they felt that their property had a negative effect on the health of someone in their home.

Fifty-three households benefited from direct installations in their homes of equipment such as replacement gas boilers, heating controls and loft insulation.

It is anticipated the NHS will make savings against the total project cost of £358,000, through reduced attendances at general practice and A&E.

“I’d like to see how we can bring all of our data together, not just health and social care, but police and fire services, so that we can really look at populations in the whole,” says Felicity Cox, chief executive of BMLK ICB.

“If we can get the data together and use single, shared workers across lots of the statutory sector and the voluntary sector, we can make a real difference to both helping [people] and making it simpler for them to support and help themselves.”

Improving health outcomes in Birmingham and Solihull

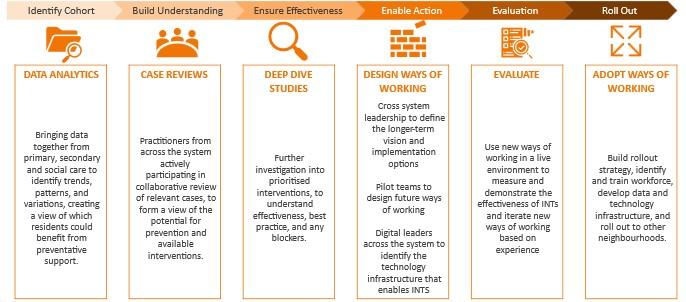

Integrated neighbourhood teams, known as INTs, across Birmingham and Solihull (BSOL) are aiming to improve the health outcomes of circa 20,000 local people over the next two years.

These teams will provide “better joined-up care for people who already have long-term chronic conditions, who are often getting care from lots of different parts of health and social care at the moment in a way that isn’t working as well for them as it could,” explains Richard Kirby, chief executive of Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.

Cross-system BSOL data, connected up for the first time, has enabled the ICS to identify a cohort of patients to target with this new approach.

“We’re bringing lots of different people with different expertise in the same place to share experiences and what works and what doesn’t work to solve a patient’s problem,” says GP Dr Nahmana Khan. INT BSOL partners include primary care services, Birmingham City Council, Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council, NHS providers and community, voluntary and faith organisations.

Aligning an integrated neighbourhood team to all 35 primary care networks within the next two years could generate a potential £20 million-plus financial benefit to the system, initial data evaluation modelling suggests.

The programme “gives us a chance to make a fundamental difference to people for the long term,” says Richard Kirby.

Creating the conditions for health in Surrey

Surrey Heartlands ICB has been supporting Growing Health Together as a place-based approach to population health, given the pressing need to tackle inequalities in health status, access to care and wider determinants of health. The NHS Core20PLUS51 strategy recommends integrated care systems focus resources on the most deprived 20 per cent of the population and those groups who experience poorer-than-average health outcomes. Place-based approaches offer a way to address the underlying causes of these inequalities.

Growing Health Together is a place-based approach which is supported by the East Surrey Leadership team and focuses on prevention and health creation underway in neighbourhoods. It mobilises and connects the assets of individuals, communities, organisations and the built and natural environment, to co-create improved health and wellbeing outcomes from the ground up.

Dr Gillian Orrow is a GP and co-founder of Growing Health Together, which helps primary care networks collaborate with community members and local organisations to improve health and prevent disease.

Born of an idea in the surgery coffee room, Growing Health Together has grown into a model which is embedded across the local health system.

“As a GP, patients used to come to me every day with different stories but the same message, recounts Dr Orrow, “the healthcare solutions on offer weren’t getting to the root of their problems.”

“I wouldn’t be depressed if I had more friends,” they would say. “My children wouldn’t be obese if I knew how to cook.” “My diabetes would be manageable if the pavements were less cracked and I could cycle to work.” “My daughter wouldn’t have asthma if there was less air pollution.”

In response, she set up conversations to find out what others in her community thought. “We met incredibly passionate people who could see massive potential to improve things in our area but who had no means to access resources to put their ideas into practice.

“The idea behind Growing Health Together was to help bridge this gap, providing resources for community members to co-create improved conditions for community health. Help could be in the form of funding, mentoring, connecting people, or finding physical space,” she says.

Over the past three years diverse initiatives have begun to flourish in the neighbourhoods of East Surrey, including:

- peer support groups for carers

- perinatal support for South Asian women

- creative arts sessions for refugees

- citizen science water quality monitoring

- community food-growing for families

- African cultural events offering food, belonging and health checks

- inclusive golf for autistic people

- gardening and food-growing initiatives

Health and wellbeing networks are now being established across East Surrey to act on the issues and opportunities identified by local people.” These networks are tackling issues that simply wouldn’t have been possible without those of us living and working in an area coming together.”

Dr Orrow reflects that the role of Growing Health Together has been to make it easy for health to be created locally. “We have welcomed a mosaic of diverse contributions, connecting people, places, organisations and resources so that great ideas have come to life."

"Taking small steps to connect with, listen and respond to community members, particularly those who have been underserved by health services in the past, can unleash huge energy and potential for positive change."

For those looking to adopt a similar approach, Dr Orrow’s advice it to “invert the foundational assumptions of healthcare.” “Rather than start with diseases and how to fix them, start with the evidence base on health and the conditions in which it is created.

This shifts health “from a concept of scarcity, to one of abundance. And with it, shifting long entrenched patterns and perceptions around power and agency when it comes to our health."

Localised and connected

Are integrated care systems helping to improve population health outcomes? As these examples show, they are, but there is still a long way to go. Improving health is not just about treating conditions, it is much more complex than that.

“Whole-system responsibility is vital to combat health inequalities and to help improve population health, says Dr Kathy McLean. "It’s only by having a holistic approach across the whole of the health and care, voluntary and wider public sector that this will work."

She adds that the system needs to be targeting those with the poorest health, in their own homes, and moving away from a focus on hospitals as the first port of call. "For this, services need to be more localised, created by, and connected with communities – we need a continuum of services from public health to hospitals, from social care to GPs, from community care to the ambulance service."

Further information

Find out more about improving outcomes in population health and healthcare.