Key points

There are growing parallels between local government devolution and integrated care systems (ICSs), in terms of a genuine and shared interest in geography, place, role, purpose and outcomes. Leaders are now actively asking how they can work together to best serve their populations.

In spring 2023, the NHS Confederation and Local Government Association jointly established a Health and Devolution Working Group to understand the priorities, opportunities and challenges in bringing together health and local government devolution.

This report builds on the rich learning from the working group and sets out why ICSs and devolved administrations (referred to throughout this report as combined authorities) should work together to jointly improve health and support economic prosperity, how they can maximise their collective impact for their shared populations, and what government needs to do to support and accelerate the health and devolution agenda in future.

Devolution in England is the delegation of powers, programmes and funding from Westminster to local government. As of November 2023, devolution deals have been agreed with 17 areas in England and this trend is set to continue and accelerate. With every part of England an ICS, we

will see increasing and sustained interactions between these models.Even before the pandemic, there was a growing focus on fostering more inclusive forms of growth that balance economic and social development and seek to spread wealth much more evenly across places. Given the tumult of the past four years and the current state of the economy, it is rapidly becoming apparent that health, and the NHS, plays a key role in our prosperity. In recognition of this shift, health is now explicitly and implicitly part of many local devolution deal discussions.

In many parts of the country, local devolution arrangements are already an integral part of an ICS. In all current combined authority arrangements, local authorities are statutory partners in the ICS, while the mayoral combined authority (MCA) as a body itself is often represented on

system partnership boards. With these building blocks already in place, the challenge is to understand the commonality in reforms, and further develop the relationships between NHS and local government partners to better understand and use their collective value.It is important when seeking to understand the connections between health and devolution that leaders are firstly able to visualise, comprehend and explain what closer, more effective integrated working could feel like for colleagues on the front line and, importantly, what it would mean for local populations. This report articulates a new central vision for the shared future for health and devolution.

While this central vision can underpin health and devolution more broadly, local leaders will be required to implement it according to their own context and nuance. We believe making this new vision for health and devolution a reality will require a phased, three-stage approach, developed

through coordinated local leadership and sustained national support.These three steps include: focusing on people and the places where they live and work; supporting populations to improve their own health; and recognising that everything has an impact on health. For each of these steps, this report sets out the context, findings, national

recommendations, local priorities and illustrative case studies.Delivering on these steps, and this report, will involve stretching what we can do within existing frameworks, duties and powers, before understanding what is needed to go further still; increasing and resourcing local capacity and capability; focusing on community engagement and empowerment; understanding and using soft power and system working; and above all, consistently engaging and co-developing a future of shared thinking, shared projects and shared positions.

As the report makes clear, we believe:

Health, and health metrics, should be prioritised by government as a formal part of negotiations for future devolution deals, given their importance for and relevance to economic prosperity, the growing interest from system leaders and the clear commonalities in ongoing reforms.

The ICS-combined-authority relationship should be recognised by government and national bodies as one of equals, fostering a mature, two-way relationship and acknowledging the support needed to ensure system leaders have the capacity and capability required to best deliver on their potential.

While no universal operating model to align health and devolution locally exists, it is important ICSs and combined authorities create a positive vision for integration for their local populations, underpinned by a series of thematic priorities which can guide leaders on where and how best to work together.

The timing of this report is important. There is a narrow window open in which to simultaneously look back and learn from past approaches to devolution from either a geographical or a health and care perspective, but also to look forward at what a more standardised approach to decentralisation might look like and entail, before various reforms make merging these vital areas too complex a task.

Foreword

Introduction

Health and devolution: the right issue at the right time

Local government devolution has been seen as an increasingly important issue for integrated care system (ICS) leaders to understand, engage with and influence. While local and combined authority leaders already play an integral role in their ICS – including in pursuit of the core ICS purpose of helping the NHS support broader social and economic development – there appears to be much more they share in common and which needs further exploring as the two-way nature of this agenda emerges.

This agenda is developing at pace too. Both main political parties are committed to devolution, with new ‘trailblazer deals’ being announced changing the nature of local governance. We are also seeing greater interest in the contribution health and care services play in supporting

local growth and prosperity.

With ICSs established across the country and focused on addressing long-term population health, we believe there is a pressing need to develop a joint understanding of the opportunities and challenges of local government and health devolution and to ensure our leaders are much

more closely aligned during these uniquely challenging times.

Understanding our approach

The NHS Confederation and Local Government Association, through three of its boards, jointly established a Health and Devolution Working Group in March 2023. Co-chaired by Sir Richard Leese, chair of Greater Manchester Integrated Care Board and Dr Kathy McLean, chair of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire and Derby and Derbyshire integrated care boards, the purpose of this group was to understand the priorities, opportunities and challenges for leaders in local government devolution areas and ICSs in bringing together health and local government devolution.

The working group was diverse, hosting ICS, integrated care partnership (ICP) and local government leaders along with a range of invited subject-matter experts and policy decision-makers from other sectors. Over the course of six months, the working group met a number of times, discussing a range of emerging themes which, when taken together, should help inform local practice, make national recommendations and start an ongoing, mutually beneficial conversation.

This report is an attempt to bring together the rich learning from these discussions and to support local leaders to work together to make a difference for their communities. It sets out:

- why ICSs and combined authorities should work together to jointly improve health and wellbeing outcomes and support growth and economic prosperity

- how ICSs and combined authorities can maximise their collective impact and add value to place-based partnerships – including the key priorities for local leaders to focus on and examples of good practice

- what national government and arm’s-length bodies (ALBs), such as NHS England, need to do to align, support and accelerate the ICS and devolution agenda.

While there were gaps in the collective knowledge of those present at our roundtables about, for example, what devolution entailed or the nuance of ICS decision-making, what was particularly striking was the shared appetite and support for much closer working relationships and a better understanding of what partners could achieve together, both now and in future.

This twin approach is important given the fiscal constraints many find themselves in. Put simply, our full potential can be hard to visualise when there is so little money. Part of what we are aiming to achieve in this report is to put in place the relationships which can jointly focus on the areas that matter today and which can be transformative if, and when, there is more financial headroom in future.

The consensus from the working group was that this was the right issue to focus on and this is the right time.

Terminology

Throughout this report the term ‘combined authority’ (CA) is used as a collective term for all types of authorities that have been granted a devolution deal. This includes combined authorities with and without mayors, combined county authorities with and without mayors, or single county deals with and without elected leaders.

Combined authorities or combined county authorities are corporate bodies formed of two or more council areas, established with or without an elected mayor. They enable groups of local authorities to take decisions across boundaries on issues that extend beyond the interests of any individual local authority. They are legal bodies set up using secondary legislation but are locally owned and must be initiated by the councils involved.

A single county deal is where additional powers and funding are given to the upper tier county council. Depending on the level of the deal provided, the council leader may have to be elected rather than appointed by the leading party.

Merging the twin tracks of health and devolution

It is important that this focus begins with a shared understanding of both the devolution and ICS journeys, closing the knowledge gap that leaders repeatedly reported at our roundtables. In doing so, the striking parallels between these two approaches to greater decentralisation soon become clear. The question then is how, where and when do we attempt to merge these twin tracks?

Background and purpose of English devolution

Devolution in England is the delegation of powers, programmes and funding from national government, in Westminster, to local government. While the Greater London Authority (GLA) was created back in 2000 comprising the Mayor of London and the London Assembly, the process of English devolution in the current context began in earnest in 2014 when the coalition government signed a deal with the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA).

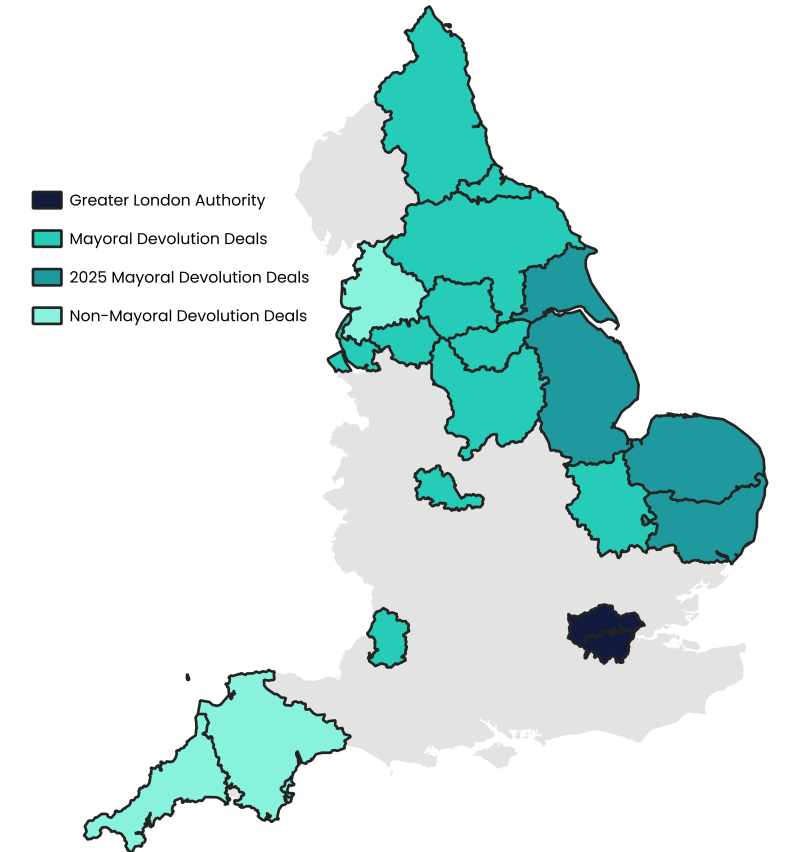

As of November 2023, devolution deals have been agreed with 17 areas in England. This trend is set to continue and accelerate (see maps below) with, for example, three more deals announced in the 2024 Spring Budget. The 2022 levelling up white paper set out the mission that by 2030, every part of England that wants one will have a devolution deal.

For this form of devolution, powers must be transferred to a body with a leader who is directly elected by the local population, ensuring direct accountability to the local population. This will normally mean the establishment of mayoral combined authorities (MCAs) by two or more local councils, which are statutory bodies led by a locally elected mayor. However, powers can also be transferred directly to councils with a locally elected leader, as is the case in Suffolk, Norfolk and Cornwall.

Figure 1: Devolution progress in England

Although the government has not definitively stated the key purposes of devolution, successive government policy often identifies three overarching principles:

- economic growth

- better and more integrated public services

- enhanced public engagement and accountability.

In practice, the deeply entrenched inequalities between various areas of England are an important motivating factor for the proliferation of devolution deals. Were devolution to be widened and deepened there are potentially significant benefits, with areas able to govern relatively autonomously in the best interests of their local populations, tailoring policy to local priorities and circumstances, and departing from the traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach seen in English governance.

Typical powers

There are a number of powers and budgets that have been made available to most areas in devolution deals since 2014, with the most notable being:

- Investment funds: 30-year investment fund, equating annually to between £15 million and £38 million for each combined authority, that can be flexibly allocated to support local economic growth.

- Adult Education Budget (AEB): Funds education and training courses for adults aged 19 and over.

- Business support: ‘Growth hubs’ which help local businesses access services such as accountancy.

- Fiscal powers: In addition to the power to impose a precept on council tax bills, most combined authorities retain all business rate revenues collected in their area.

- Transport: Most devolution deals have included a multi-year transport investment budget. Going forward, the aim is eventually to replicate the simplified, consolidated funding settlement given to greater London.

- Planning and land use: Many combined authorities have the ability to create spatial plans for the use of land (for example, for infrastructure and housing) in their area.

In addition to these core powers, further ‘special’ powers have been offered to what is presently a limited set of combined authorities. These include powers relating to police and fire, justice, housing, and, of course, health.

Recent ‘trailblazer deals’ have expanded the responsibilities of some combined authorities in the areas of transport, adult education and housing (including the Affordable Homes Programme and funding for brownfield development). Importantly, these deals commit to providing a single funding settlement in the 2025 Spending Review, akin to the method of funding of government departments. These trailblazer deals have been formalised with Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, while some other areas have been offered a ‘level 4’ devolution deal with enhanced powers but without a single settlement: Liverpool City Region, the North East, South Yorkshire, and West Yorkshire.

Combined authorities (and directly elected mayors in particular) also wield significant ‘soft’ power, due to their high-profile position and mandate from the local population. This allows them to set local priorities, even those which do not relate to powers available locally, and bring together relevant public and private sector partners.

Where does health feature?

Devolved powers relating to health are of particular interest to this report. The GMCA and GLA are the only devolved bodies currently with responsibilities for the health of their local populations. However, the recent ‘trailblazer’ devolution deals have mentioned health in the context of other powers, such as employment, and, importantly, the updated Levelling Up Framework (see appendix 2) now allows for an explicit public health duty for level 2, 3, and 4 deals. In devolution deal terms, health is now explicitly part of the picture, recognising the significant and growing influence that wider socioeconomic circumstances have on health, and also the importance of population health to economic growth.

Examples of health in existing ‘devo deals’

Devolved health powers held by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority:

- Health responsibilities were devolved to the GMCA in 2015.

- A Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership Board (GMHSPB) was established consisting of a Joint Commissioning Board (JCB) and a Provider Forum. The JCB comprised local government, clinical commissioning group (CCG) and NHS England representatives. The Provider Forum comprised service providers, such as acute trusts and ambulance trusts.

- The GMHSPB pooled the commissioning budgets of CCGs and the social care budget of local government, using section 75 of the National Health Service Act 2006 to commission integrated health and social care services in Greater Manchester.

- It is important to note that the Mayor of Greater Manchester does not have any formal role in health devolution agreements, although the mayor would be expected to have significant soft-power and influence.

- This GMHSPB has since been transformed into the Greater Manchester Integrated Care System.

Devolved health powers held by the Greater London Authority:

- Since 2007, the Mayor of London has had a statutory responsibility to produce a health inequalities strategy.

- The mayor must also consider public health when forming strategies for other policy areas: for example, the Healthy Workforce Charter in the London Economic Development Strategy

In 2015, further health responsibilities were devolved to the GLA, and these were subsequently expanded in 2017. Key points include:

1. The establishment of a London Estates Board, which receives all money raised from land and property sales within London, and subsequently re-invests this to support city-wide priorities

2. A place-based framework for system regulation, which is aligned with national regulatory partners

3. The establishment of a London Workforce Board to coordinate all training and workforce development within London

4. The delegation of transformation funding to a London Health and Care Strategic Partnership Board.

Public health powers held by combined authorities:

- The East Midlands Devolution Deal is one example which includes a public health duty. The proposal states that: ‘To complement and support action by the Constituent Councils, the East Midlands MCCA will take on a local authority duty to take action to improve the public’s health concurrent with the Constituent Councils. This will allow health to be considered throughout the East Midlands MCCA’s activities as well as enable work on local issues where health plays a key role, for example tackling homelessness and rough sleeping.’

Health as part of broader public service reform:

- The North East Devolution Deal has an explicit section on public service reform, which incudes a focus on: place-based health and care, with a new ICS-devo region-wide approach to social care collaboration, the health and social care workforce, and market shaping; healthy ageing, exploring, with partners, potential for a new ‘Golden Triangle’ to develop stronger partnerships between the North East, Edinburgh and Glasgow; and population health and prevention, developing a Radical Prevention Fund that will reshape existing funding away from acute services and into preventative action.

- The West Yorkshire Devolution Deal states that: ‘Government commits to working in partnership across Departments and having further discussions with West Yorkshire to explore the feasibility and opportunities around an “Act Early” Health Institute, based in the region. The institute would be a whole system test bed to evaluate the long-term health and economic consequences of early life interventions and build an evidence base on long-term outcomes for children.

Assessing the early impact on health

Measuring outcomes is a critical part of devolved working. With health still building up a role in devolution deals, the evidence base is still developing. However, early findings from Greater Manchester support the theory that, where health outcomes are embedded within place-based strategies, they can drive improved outcomes. A University of Manchester study which evaluated changes in Greater Manchester from 2016 to 2020 compared to the rest of England, was published in the journal Social Science and Medicine in March 2024, highlighting that the deal enabled public service leaders to make significant improvements in many parts of the health system. These improvements included 11.1 per cent fewer alcohol-related hospital admissions, 11.6 per cent fewer first-time offenders, 14.4 per cent fewer hospital admissions for violence, and 3.1 per cent fewer half school days missed from 2016 to 2020. More emphasis and consistency in capturing the quantifiable impact on health from devolution, and how context specific these impacts are is an essential step in realising the potential.

The ICS journey

Integrated care systems (ICSs) are partnerships of the organisations which deliver health and social care in an area, including of course local and combined authorities. These systems include primary and secondary care providers, local government, social care providers and voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise (VCSFE) organisations.

ICSs are led by an integrated care board (ICB) and integrated care partnership (ICP). The ICP is responsible for developing an integrated care strategy, which the ICB must have regard to when developing its five-year Joint Forward Plan and carrying out its work.

ICSs were set up in recognition of the need for more joined-up health and social care services and have been tasked by NHS England to bring organisations together and champion integrated care to achieve four key purposes:

- improve outcomes in population health and healthcare

- tackle inequalities in outcomes, experience and access

- enhance productivity and value for money

- help the NHS support broader social and economic development.

As work by the NHS Confederation has made clear, the fourth of these purposes is perhaps the least well understood, but is critically important to the interplay between devolution and ICSs.

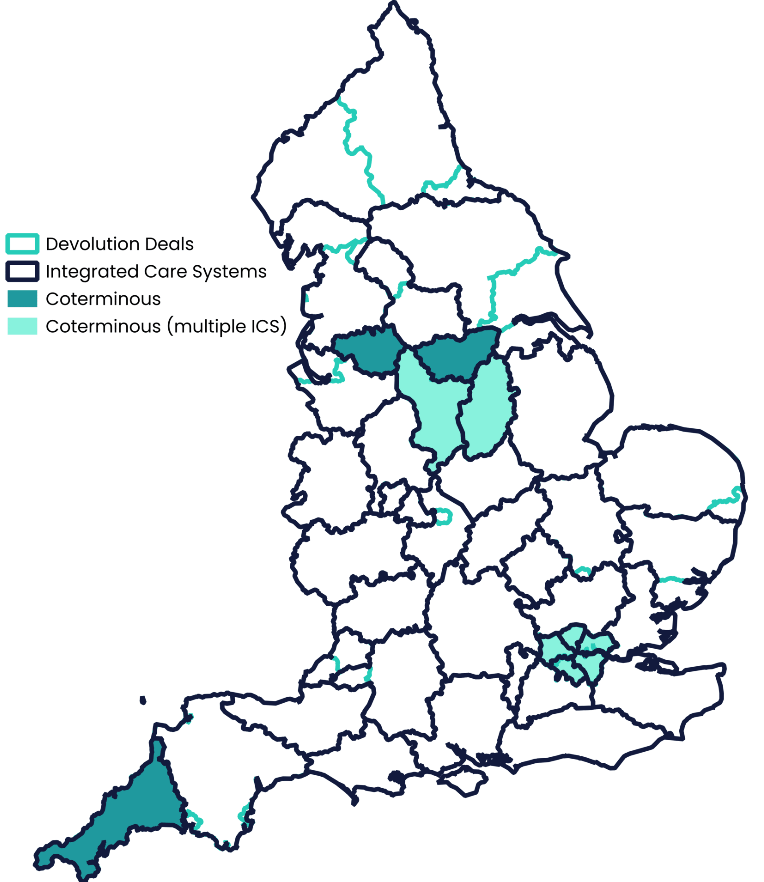

The 42 ICSs in England vary enormously in terms of size, resources and population health. As shown on the map below, some are co-terminous with combined authorities or other devolution arrangements, some have a partial overlap (including multiple ICSs working with one CA and vice versa) and many have no links at present, though this will certainly change as more devolution deals are agreed.

Figure 2: Where devolution deals and integrated care systems overlap

Repositioning health, rebuilding the economy, reinvigorating communities

“It is clear that health and prosperity are interdependent. We can’t have a healthy economy without a healthy population, and vice versa.” Matthew Taylor, Chief Executive, NHS Confederation

Even before the pandemic, there was a growing focus on fostering more inclusive forms of growth that balance economic and social development and seek to spread wealth much more evenly across places. Given the tumult of the past four years and the current state of the economy, it is rapidly becoming apparent that health, and the NHS, plays a key role in the nation’s prosperity. Recent analysis commissioned by the NHS Confederation demonstrated that for every £1 invested in the NHS, £4 is generated for the local community through increased economic growth. This is largely for two main reasons: the influence of population health on workforce productivity and the direct role of the NHS itself as an anchor institution.

The influence of population health on workforce productivity is significant. Chronic physical and mental health conditions lead to individuals being less productive at work or exiting the workforce altogether. Currently, in the UK over 2.5 million adults are unable to work due to long-term illness. It is important to note that chronic illnesses are most prevalent in our most deprived areas, including the many rural and coastal communities in England, meaning the impact on productivity can be felt the greatest here.

Anchor institutions are large organisations that have a significant stake and influence in their local area, and include the NHS, councils, universities, sports clubs, business and VCSE organisations. In supporting local and combined authorities to improve resilience in place and address the social determinants of health, the NHS can directly help by, for example, providing well-paid, secure work and professional development opportunities, purchasing from local suppliers, and using its buildings and spaces to support local communities.

The NHS Confederation has led on how ICSs can put economic and social development at the centre of their strategies; moving from individual organisations running isolated projects with their communities to a coordinated, system-wide view of what needs to change (‘anchor systems’). The issue of stagnant productivity may date back to 2008, but the structures we have, the salience of health, and the willingness to work together to address it presents new opportunities.

Devolution and ICSs: where the tracks meet

In many parts of the country, local devolution arrangements are already an integral part of an ICS. In all current combined authority areas for example, local authorities are statutory partners in the ICS, while the mayoral combined authority (MCA) as a body itself is often represented on partnership boards. In Greater Manchester’s case, this is through the mayor and MCA chief executive, while the Mayor of South Yorkshire also chairs the respective ICP. With these building blocks already in place, the challenge is to further develop the relationships between NHS and local government partners to better understand and use their collective value.

Health and devolution are both broadly underpinned by two complementary shifts. Firstly, dating back to 2007, the Sir Michael Lyons review saw the role of local government moving from one of service provider to ‘place shaper’. Secondly, and more recently, in health, reflected in the creation of ICSs, there has been a shift from a focus on the role of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England, the regions, trusts and target-driven primary care, to more of a social emphasis, involving joined-up national health policy, ICSs (especially ICPs), places and integrated neighbourhood working.

While service delivery will always be vital, and contains important improvement and innovation, place shaping and a social model of health improvement are what bind the NHS to partners. Local places cannot prosper, and institutions are not sustainable, just by relying on the basis of a core safety net of services.

These shifts highlight the parallels in the moves of health and care towards local autonomy and greater integration vis a vis the recent process of devolution to local government in England. This shared journey offers real and tangible opportunities, though cultural differences and challenges between these two significant public sector partners do still exist, as well as misalignments in geography. Done right, health and devolution can bring significant benefits for local communities. Misuse the opportunity though and it may inadvertently undermine this path to subsidiarity.

Strong, successful ICSs will be vital to the success of devolution, both directly and indirectly. Directly, because combined authorities in particular will begin to take on more responsibilities for the health of their local population and will need the support and engagement of the health and care sector. Indirectly, because ICSs will improve the health of these local populations, which is necessary for economic growth, and ensure the local NHS is supporting broader social and economic development.

Equally, devolution will be critical to the success of ICSs. Many of the causes of ill health lie outside the NHS’s direct sphere of influence, with local economic development policies and planning decisions having measurable consequences for public health and health budgets. These costs need to be accounted for and integrated in wider health strategies. Working in close partnership with devolution deals will help ICSs more effectively shift resources towards mitigating the effects of these circumstances, ensuring improvements in population health and the long-term sustainability of the health and care system.

Devolution is certainly on the mind of ICS leaders. The State of Integrated Care Systems 2022/23, the NHS Confederation’s ICS Network’s annual survey of ICB and ICP leaders, reported that:

‘…while ICS leaders identify a number of areas where progress has been made, they also pinpoint areas where progress has been slower than hoped. These include their plans and commitment to supporting greater devolution. There are positive examples of devolved decision-making and provider collaboratives that ICSs will want to build on, but as place-based partnerships and provider collaboratives mature, ICS leaders recognise the need to devolve more decisions and functions to a more local level. That is their intention in the next period of their development.’

Importantly, both devolution and ICS reforms should be seen as a means to an end, not an end in themselves. They are seeking to develop a shared vision and ambition to address shared challenges for given populations. These twin tracks of devolution and ICSs are clearly running in parallel; going forward, we need to understand how and where to make them intersect.

"The reforms face the same way, but it’s important to remember that how we got here differs. Everywhere became an ICS whilst areas have had to fight to achieve devolution. Understanding this push-pull nature helps us understand each other better.” Mayoral Combined Authority Chief Executive

Reimagining the future: where next for health and devolution?

It is important when seeking to understand the connections between health and devolution that leaders are able to visualise, comprehend and explain what closer, more effective integrated working could feel like for colleagues on the front line and would mean for local populations, whether in rural or urban settings. System leaders have a clear role in providing the intellectual scaffolding to remind people why they should want and need to keep engaging with each other during difficult, pressured times.

Many of the new ICS and devolution structures being implemented across England are complex, requiring new and existing leaders to work together in different ways to unpick challenging legacy decisions around issues such as service design, provision and funding. There is a danger that inward-facing discussions around the detail of these challenges stifle the opportunity to create a new positive way of working for the future. The roundtable discussions that informed this report were clear that such a vision was the timely, first step in reimagining the ICS-devo relationship and in articulating the shared future for health and devolution.

A new vision for health and devolution

We believe a positive, reimagined national vision for health and devolution can be built, based on five core principles:

1. Working together for our shared populations can deliver greater impact than the sum of our parts

It is the impact on communities through which the new ICS and devolution structures will ultimately be judged. The spirit required to bind closely these systems, and their respective leaders, must be one of ‘stronger together’. In this context, aligning health and devolution enables organisations and individuals to push into the areas that matter to keep people healthy and prosperous, and where they previously may have felt ‘permission’ was needed to engage.

Not only should the local impact of this way of working be greater than the sum of the individual parts currently making up a local ICS and devolution arrangement, it should stimulate and test broad new thinking, reaching out to new partners and reinvigorating conversations that in many cases have been ongoing yet sub-optimal for years.

2. Aligning health and devolution can reconcile the differing national and local perspectives of the future of health and care

As the gap between the operational demands of today and the strategic needs of tomorrow widens, health and care leaders face being stretched in two different, contradictory and competing directions. National ministerial and NHS leadership will demand increased central grip and a focus on operational priorities, such as access and waiting lists, while local partners will want the NHS to help develop more resilient, thriving communities and economies which collectively look to address public service demand.

Resolving this contradiction will require deliberately open and careful local partnership working, particularly through the ICS-devo relationship, to support new approaches to place-based service planning and delivery, to advocate collectively across and within areas, to facilitate the sharing of resources and ideas, and to build trust between traditional and new partners that can challenge protectionist behaviour or failures in policy.

3. Being clear what the ICS-devo relationship can offer national government can secure our future

The UK’s national political cycle often inhibits good policy development, with plans rarely lasting beyond a single parliamentary term. Ministers are, though, increasingly cognisant of the limitations of changing local practice solely through national levers. At the core of the ICS-devo offer to national leaders should be a far richer understanding of place-based connections, the supplementary evidence and nuanced understanding of what works over a longer time period of between ten and 20 years and in different local economies, and a greater insight into the nature of the interactions between separate policy areas and government departments. This triple approach presents a compelling case for change to whomever is in power and can help formalise a future for English devolution where local is the default.

4. Modelling a new way of working which places health and care at the heart of broad strategy can help our populations and our partnerships prosper

Further calls for increased autonomy for ICSs will need a strong evidence basis on which to build. Alignment on health and devolution will enable ICS leaders to showcase the potential of this tier of administration, themselves modelling new ways of working, including peer-to-peer support and learning, and co-developing strategy that is health related and cross-Whitehall, rather than simply isolated NHS policy.

In doing this, the model of English devolution can be shifted away from its explicitly economy-based roots, making it more about promoting economic, physical and social wellbeing and resilience so that communities are self-sustaining. This will be a hugely significant development in this agenda at a point in time where many new local areas are seeking broader agreements and deals. Modelling the future, which is increasingly possible with tools to measure the causes and costs of public health, will help us move the dial from both ends.

5. Understanding the counterfactual of not aligning health and devolution will escalate the pace of change

Much of what needs to be done locally to help determine a more preventative state has already been published and championed by a succession of national and system leaders, including notably the Rt Hon Patricia Hewitt in her April 2023 independent review of ICSs. The ICS-devo relationship is perhaps the most important lever in realising this and other reports, and in escalating the pace of change at which we all operate and through which we can truly move on prevention and population health.

This will, however, require real will and challenge from leaders, including being more vocal with each other, with local partners and with national government about the consequences of not acting to deliver this future. An empowered ICS and combined authority partnership is vital in ensuring the sustainability of our public services, but also that they engage and support communities in new, thought-provoking ways that make clear the choices involved.

While this central vision can underpin health and devolution more broadly, local leaders will be required to implement it according to their own context, recognising both the complexity of their system but also how these complexities themselves vary.

We believe making this new vision for health and devolution a reality will require a phased, three-stage approach, developed through coordinated local leadership and sustained national support. Our report proposes the following three key steps in this journey:

Figure 3: Delivering on health and devolution: three key steps

Step 1: Focus on people and the places where they live and work

The starting point for our roundtable discussions, and for the subsequent themes which emerged, was a real and sustained focus on the centrality of place and the people within. Geographies may not always be co-terminus, but there will be shared places and populations that an ICS and combined authority collectively serve and/or represent. This one constant can bind the local focus and prioritisation and unite an ambition, around which a compelling case for devolution to best support them can be made.

“The regulatory context in which we as leaders operate may differ, our working cultures may occasionally clash, and we often perceive different value in partners, but the people we work with and for should provide a common basis on which to build a thriving, successful relationship which, in turn, supports a thriving, successful place.” Working Group Co-Chair

While the challenges facing local leaders across public services are often common in nature, traditional responses can be sector-specific, place-blind and partial in impact. Whether in densely populated urban areas with extremes of need or more rural areas where the breadth makes scalability difficult, focusing on common place challenges, and developing shared ambitions for both population health and economic prosperity, can actively support those on the front line to deliver. This first step will involve maximising the respective strengths of partners and better understanding what more is needed from national leaders.

In particular, we found that:

- Local ICS and devolution leaders strongly believe there is a vital requirement to better understand their communities and to subsequently focus their work alongside place, people and partners, rather than from their organisational or sector perspective. In doing so, the early framing for a new sub-national approach to spatial issues such as accountability, financing and regulation may emerge.

- Devolution can bring more shared responsibility; clarifying the roles and reach of individual partners, and being clear about how ICSs and devolution deals can add value to place-based partnerships, including their contribution to building a long-term route-map for integrating public services and empowering citizens. It will also help understand what more is needed to accelerate local progress.

- There is a need to be much smarter with the spatial understanding of what can best be done at which level, including supporting the development of place-based approaches that commit local partners to joint policies and ways of working. Such a bottom-up approach to governance supports place, enables a more formal way of devolved working and is consistent with the principles of subsidiarity. To explore this first theme, ‘focus on people and the places where they live and work’, we looked in detail at both people and place.

National recommendations to realise local potential

- In the absence of a standard sub-national governance model in England, government and NHS England should give local ICS and combined authority leaders the freedom and flexibility to determine and embed an operating approach that works for their areas.

- Government and NHS England should ensure associated national targets and priorities are aligned, supported by a forum bringing together senior officials from departments with a shared interest in the agenda and ICS and combined authority representatives, as well as key local partners and wider stakeholders.

- Government should prioritise funding to support the capability and capacity of local ICS and combined authority partnerships to deliver for their populations.

Local priorities around which a renewed ICS-devolution partnership can focus

| People | Place |

| Focus on getting the best outcomes for the shared communities you serve, rather than for your own organisation or sector. | Make place the starting point for all devolution discussions – it is meaningful to local people in ways that combined authorities and ICSs are often not. |

| Ensure joint community engagement is purposeful, ongoing and acknowledges the diversity of perspectives. | Develop place-based strategic approaches which commit local partners to joint policies and working. |

| Build on what works for local people; adding value, revising and improving only where necessary | Be smarter with your spatial understanding and what you can collectively do, given subsidiarity is not linear |

People: the shared populations we are working with and for

It was clear from the roundtable discussions that while communities were often at the heart of both ICS and devolution strategy, there were limitations in their participatory approaches and thus how much system-level decision-making took into account their needs and their voice. For any joint approach to public service reform to be successful it will require a better, and importantly shared, understanding of the nuance, diversity and priorities of the population being served and the assets that connect and support them.

The people-related priorities that should shape future ICS and devolution working are:

1. Focus on getting the best outcomes for the shared communities you serve, rather than for your own organisation or sector

One of the more challenging aspects of place-based working is moving away from an institutional or sectoral perspective, particularly when practice is well ahead of policy in terms of action, accountability and assurance. There is a need for ICS and combined authority leaders to be working together to position their work alongside places, people and partners, rather than seeing one particular player locally as making a critical difference.

In the continued absence of a robust, standardised place approach to development or measurement, a focus on shared local outcomes can anchor joint discussions around strategy, priorities and delivery, and support constituent partners to be less protectionist. In doing so, systems can focus on issues that matter to local communities, engaging those with lived experience of multiple public services and changing the culture of how they themselves work. This may help define the future frameworks needed to formally support place-based working, ensuring they build on both practice and evidence.

2. Ensure joint community engagement is purposeful, ongoing and acknowledges the multitude of perspectives

The need to continuously work with and alongside communities to ensure they can actively shape, influence and evaluate decision-making is a clear priority. Community engagement has often been viewed as one-way, legalistic and lacking empathy, particularly when led by NHS organisations. Working together across ICSs and combined authorities enables new opportunities to unite around a common agreement on the people leaders are talking about when making different decisions, and when working at different levels.

Particular care and attention will be needed to ensure marginalised communities are aware of the purpose and parameters of local engagement and feel part of the ongoing debate, having a voice directly and/or through representative VCSE organisations. The new structures themselves can also suffer from a lack of public awareness. Better engagement and a stronger focus on storytelling, including through local media, can help explain to populations what devolution and integrated care means for them, bringing people on the journey and improving outcomes.

“We need to be clear with people whether this engagement is about insight generation or whether it is about service redesign, co-commissioning or co-production, and who is doing it.” ICB Director of Strategy

3. Build on what works for local people; adding value, revising and improving only where necessary

There is often a tendency when setting up new structures to ‘start again’, overlooking what is already working well or simply requires support, readjustment or gradual evolution. Community engagement is a good example of a function which partners, particularly local government, have led on in different and successful forms. Whether through formal settings, such as Town Hall debates, or informal ones such as county shows, such approaches have built up trust, involved a range of local citizens and empowered better outcomes.

The role of the ICS and combined authority partnership should be to understand what forms of community engagement and involvement are already in place locally and how to add value to them; revising, expanding and/or improving only where necessary and helpful. The system perspective could itself be seen as too remote by local communities, emphasising the importance of governance, accountability and leadership, and understanding who is best placed to lead on this engagement.

Place: the starting point for discussions and the spirit of subsidiarity

Leaders at the roundtables reported that a common concern of local partners and constituent leaders was that the new structures, such as mayoral combined authorities and ICSs, will suck power upwards, away from the communities they are making decisions about and out of the hands of those institutional leaders delivering services. This is the antithesis of subsidiarity and runs the risk of disempowering and destabilising local leadership and place initiatives, making their jobs harder and limiting the collective ability to support populations. The roundtables focused on using place as the starting point for discussions about how an ICS and devolution arrangement can work effectively.

The place-related priorities that should shape future ICS and devolution working are:

1. Make place the starting point for all devolution discussions – it is meaningful to local people in ways that combined authorities and ICSs are often not

While much has been made of the new statutory sub-regional structures in health and care and more broadly in devolution, place is still where much of the actual delivery of public service provision happens and where integration, or the lack of it, is most noticeable to colleagues and communities. The very principle, and test, of subsidiarity is place by default and this should underline all policies, decisions and delivery.

The related challenge for ICS and devolution leaders is to understand how to add value to local arrangements by doing things across their larger footprint; focusing on common ‘wicked’ problems, spreading or scaling innovative practice and addressing unwarranted variation. This requires a continuous two-way conversation, accepting ambiguity and, importantly, the separation that often exists between accountability and delivery. While place is seen as the starting point, it should not however be used as an argument to defend practice that simply isn’t effective.

“Each local place is complex, and central government doesn’t have the skills to deal with this level of complexity.” University Vice-Chancellor

2. Develop place-based strategic approaches, which commit local partners to joint policies and working

The sub-regional landscape in England resembles something of a patchwork, with various devolution areas having differing degrees of local autonomy. Similarly, ICSs – although covering the whole country – are understandably taking differing approaches to their governance and partnerships. There will be common priorities that link the ICS and combined authority tier with place, and successful working will require a constant echo between the two, with place vital in both contributing to and interpreting these issues.

Rather than trying to fuse two different structures roughly together, ICS and devolution leaders stated they preferred to focus on co-developing strategic place-based approaches which better commit local partners to joint policies and working over the long term. In some cases, places are building on anchor networks local partners have established, in others using missions-based approaches. Integral to the success of these place-based methods are innovative forms of community engagement and data through which to better understand each other and the locality.

3. Be smarter with your spatial understanding and what you can collectively do, as subsidiarity is not linear

Even with a commitment to offer devolution to every local area that wants it by 2030, the sub-national governance of England will be uneven in speed, scale and subject – something government at some point must address. This does though present different opportunities to different areas at different times, placing an increasingly important emphasis on the framing of ‘place’ and the understanding and use of spatial policy and approaches. Starting from the bottom-up is a good way through this complexity; complementing and challenging system-wide powers, priorities and strategies with a more granular understanding of need, provision and impact at the various levels.

While some combined authorities are seeking legal responsibilities for public health, for example, this does not mean that a duty necessarily needs to be taken away from elsewhere. Combined and local authorities, public health directors and ICSs can concurrently, and successfully, hold related powers, but it is important they understand the differing spatial values involved and agree how they will best use them.

“Co-terminosity is hugely helpful, or course, but it is not critical. Many countries face this issue and every tier of working will have some form of geographic overlaps and misalignment. Start with the population.” Local Authority Director of Strategy

“We need to simultaneously think about what we are offering to government and how we are supporting local boards.” ICB Chair

Case studies: Focus on the centrality of place and the people in them

There are examples of this theme emerging across England, including:

- Shifting to prevention: using evidence to realise this shared endeavour – the North East journey

- GM Working Well: Roots to Dental

- Towards a healthy and prosperous future – reflections from the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Metro Mayor, Dr Nik Johnson

Step 2: Support populations to improve their own health

Building on and baking in the centrality of place and people will require the partnerships and powers required to truly invert traditional ways of working. With the short-term demands on public services increasing, leaders at our roundtables felt strongly that there is a need for a renewed, collective ambition and purpose to help populations themselves to improve their own health, rather than see statutory services continue to try to do it to communities.

“The interrelationship between health and the economy, the focus on addressing inequalities and good growth, and the ambition to better utilise greater local autonomy are mutually binding, compelling and beneficial. Having a vision that will support populations to improve their own health will bring these factors together and to life.” Working Group Co-Chair

ICSs and combined authorities are aligned in many thematic areas and this partnership can set the basis for a new and long-term approach to understanding and delivering on the enablers of good health; such as transport, housing, employment and education, and skills. An increased understanding of the variables and how policies interact can drive further connectivity and better outcomes in both urban and rural areas. Such an approach will require new ways of working, and holding each other to account, but can shape places in permissive ways that encourage, connect and reward communities for their engagement and endeavour. It can also go some way to ensuring the sustainability of the individual public services citizens rely on.

This second step is about supporting and evidencing the long-term discussions about what more is needed, what powers leaders should be seeking to really make a difference and, importantly, how they would use them. In particular, we found that:

- Emerging health and devolution policy clearly face the same direction – with prevention, population health and prosperity now central to our collective aims and to our success, though there is still some way to go to deliver on this. ICS and combined authority leaders believe they need to jointly focus on the mindset, skillset and toolset needed to develop plans that are long-term, evidence-based and multi-sector.

- ICSs and combined authorities need to use existing collective powers, agency and resourcing more effectively, pooling where appropriate, and focusing on common challenges – not waiting for permission from government or national agencies to stretch what they can already do. This is important in facilitating conversations and breaking down barriers, as well as ensuring progress on the national missions in the levelling up white paper.

- Realising this potential will require capability and capacity building at the ICS and combined authority level. The necessary headspace (including time, capacity, skills, data and resources) required to understand community need, and then to coordinate and collaborate on the policy and implementation response, is no longer present in many areas and this should be a priority for national and local leaders to address.

To explore the theme of ‘support populations to improve their own health’, we looked in detail at both partnerships and powers.

National recommendations to realise local potential

- Government should offer formal and coordinated support on embedding health as part of the commitment to offer all of England the opportunity to benefit from a devolution deal by 2030.

- Government and NHS England should work with partners such as the NHS Confederation and the Local Government Association to build a strong evidence base to support joint ICS-devo investment in preventative models of care. This could include building public health into the cost-benefit analysis of economic development policies.

- Government and NHS England should proactively engage with ICSs and combined authorities collectively when agreeing new approaches to key issues such as accountability, including delivery of the levelling-up missions and the future role of the Office for Local Government (OFLOG)

Local priorities around which a renewed ICS-devolution partnership can focus

| Partnership | Powers |

| Create the capacity, resource and time necessary to fully embed community engagement, relationship building and collaboration at all levels. | Focus explicitly on both health in all policies and health policy in determining what is best needed to support and empower communities. |

| Be transparent about the ICS-devo partnerships and who you work with and why, including who benefits and how. | Do not wait for permission from government and NHS England to use your existing powers. |

| Prioritise shared data about public services and populations, not just local government and the NHS, as a key enabler to unlocking the potential. | Ensure proposals for future devolution deals involve health and build on and evolve developments that are long-term, evidence-based and multi-sector |

We discuss both these areas in more detail below.

Partnership: holding each other to account

The varying levels of awareness of the diversity and intricacies of communities is sometimes mirrored in how much, or how little, leaders know about their own local partners. Despite the overlaps, numerous ICS leaders at our roundtables expressed doubt about how combined authorities worked, and what their aims and levers were. Similarly, devolution leaders often struggled to gauge the nature of the relationship between, for example, the ICB and the ICP. For the ICS-devo partnership to fully maximise its joint potential, partners involved need the knowledge, confidence and mechanisms to challenge across traditional divides, always acting in the interests of their communities.

The partnership-related priorities that should shape future ICS-devo working are:

1. Create the capacity, resource and time necessary to fully embed community engagement, relationship building and collaboration at different levels

One of the most damaging consequences of over a decade of diminishing public funding is the lack of local capacity across and within a given place. No one partner has been exempt from tighter financial pressures and there is often no obvious institution locally with the resources and flexibility to lead. Allied to this, limited resources often push potential partners apart as they turn to look inwards, just as partnership working is required more than ever.

Devolved working requires new approaches to, for example, community engagement, relationship building and collaboration, and it will simply not reach its potential without dedicated local capacity, resource and time. Some of this may be derived by better local pooling of assets but more must be done by national government and agencies to support local leadership. Government can more closely align future national ICS and devolution policy, funding and timescales, but it should also have an explicit focus on funding local capability and capacity at this system level which can unlock local partnerships and secure better outcomes.

“If we improve our relationships across the system, we improve our capacity to manage the pressures we face.” ICP Chair

2. Be transparent about the ICS-devo partnerships and who you work with and why, including who benefits and how

ICS and combined authority leaders are perhaps unique in the combination of the macro and micro perspectives they hold. Systems are learning how to face each other but collectively they also have a key role in empowering and supporting place-based collaborations below and in negotiating with government and national agencies above. How to hold each other to account is therefore a vital question at the heart of this new relationship, and some ICS and devolution areas are developing memorandums of understanding (as in West Yorkshire’s case) or other forms of agreement.

The principles of continuous improvement, a learning culture and humility are vital, alongside transparency about who they work with and why. One area where this will be tested is with the business and investor voice, who are keen to work more with the health and care sector. Devolution leaders will be increasingly bringing ICSs into existing conversations with a range of non-traditional partners and it is important they are aware of the shared rationale behind partnerships and the mutual involvement and benefit.

“From the VCSE perspective, the NHS and local authorities are seen as two giants, with ourselves the much more junior partner. Yet we have the trust and engagement with communities an ideas about enterprise, capital and wealth building.” Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise Chief Executive

“Businesses are strong supporters of devolution. We want partners, including the NHS, to have the freedom and resources to express their need and take long-term investment decisions for their communities.” Investor

“From the academic sector, how can we help support policy-makers to use local levers? It is vital we get the maximum value and more inclusive impact out of academic research. Don’t see the university or college role in devolution as narrow.” University Vice-Chancellor

3. Prioritise shared data about public services, not just local government and the NHS, as a key enabler to unlocking potential

One of the most exciting aspects of joint ICS and combined authority working is the collective reach into the causes of issues to which leaders previously could only react. The starting point for this is a much more holistic and informed use of data, presenting a shared local picture of need, resources and challenges, including who is being impacted or missed out by existing public service provision.

There are common challenges around data, including the significant amounts of unused data, questions over how people access it and the lack of the necessary skillset. As the use of data broadens and analytical capabilities grow, there will likely be a greater appetite to break down populations to identify those most adversely affected or to target population groups to develop new policy or seek new powers around. This data is important for other reasons too.

Traditional public sector commissioning models are changing as the new structures evolve, with engagement approaches and investment priorities not as robust as they once were. Shared public service data can help drive new and more informed shared commissioning and more outcome-focused relationships with the VCSE sector.

“A benefit of greater health devolution is that we can point to a wider range of outcomes, meaning conversations with government departments are not in isolation.” Mayoral Combined Authority Director

“Devolution allows everyone to have input to the wider social and economic determinants.” ICB Chair

Powers: strengthening leaders’ ability to truly make a difference to population health and economic prosperity

The passing of powers and programmes down from the centre to local leaders sits at the heart of the English devolution approach. This ethos, approach and process is a means to an end, not an end in itself, with powers, and the local autonomy to best use them, vital in equipping local leaders with the tools to do their job. While the initial range of powers and programmes sought by many combined authorities in devolution deals focused on those areas required to grow the local economy, such as skills, transport and housing, our roundtables heard how the role of health and public service reform are now rightly seen as being of huge economic value and are more prominent in discussions with government, opening up a range of new opportunities.

The powers-related priorities that should shape future ICS-devolution working are:

1. Focus explicitly on both health in all policies and health policy in determining what is best needed to support and empower communities

All policies have a health impact, either positive or negative. The links between health and, for example, skills, transport, employment, housing and economic growth are increasingly focusing the minds of ICS and devolution leaders, highlighting the interrelations at play in both practical and strategic ways. The need is now to become much more explicit about this relationship, linking operational and policy integration and giving people agency through distributed leadership.

This will involve stress-testing current policy areas to understand how the anchor role of the NHS, for example, can support a greater impact on, and connect, communities; how differences in the implementation of policies can affect health in a positive way; and, vitally, where the gaps are for which a specific focus on devolving health policy can help. This last point will see devolution deals become much more focused on seeking additional health-related powers in future and also much earlier in discussions.

“We need to regularly evaluate the impact that devolution has had on the health of the population. What policies have had the most impact, both health specific and otherwise?” Devolution Adviser

“In negotiating our deal, there was a requirement for a business voice and a voice for the police and crime commissioner, but nothing in terms of health being pushed by government departments. That may simply be because we were asking for specific health powers, but it could be evidence of a disconnect between policy across government.” Local Authority Director

2. Do not wait for permission from government and NHS England to use your existing powers

The four purposes of an ICS, and the role of the NHS as an anchor, have seen more health leaders joining local conversations about what makes populations healthy, rather than focusing on their services – looking at the broader determinants of health, not healthcare. Devolution can, and should, accelerate this journey considerably, ensuring a mutual commitment across partners to work together to deliver better health outcomes and a better economy.

New powers may well be needed and sought to help achieve this, but the wellbeing power and general power of competence that ICS and combined authorities already collectively hold is significant. Understanding what can be done and supporting each other to share and use this effectively is vital. This will foster a culture of asking for forgiveness, rather than permission, and lay the groundwork for further devolution of health-related powers as and when local leader determine them required.

“We need a far better understanding of our collective powers, breathing space and resourcing. This will help us develop positive, impactful relationships and reduce duplicity.” ICB Chief Executive

“National government should model the same behaviours and approach that they expect of combined authorities and ICSs. In our own actions, we can model and demonstrate how government should work.” VCSE Chief Executive

3. Ensure proposals for future devolution deals build on and evolve developments that are long-term, evidence-based and multi-sector

The 30-year timeline for many devolution deals gives some insight into the long-term nature and complexity of rebalancing local economic performance and narrowing entrenched inequalities. While the NHS has suffered from severe bouts of short-termism, ICSs need to be looking to the future, using this devolution window to advocate for much longer-term vision and focus. The real mutual benefit of devolution is focusing on addressing the long-term issues holding places back. This will require ICSs and combined authorities to focus on the evidence, agreement across multiple sectors and the collective bravery and creativity needed to keep focused on the priorities as operational and political demands rise and fall.

Importantly, as we have seen with Transport for Greater Manchester, giving local leadership greater collective control over the policy framework, the associated investment, and the service specification can derive better outcomes, including financial returns. This is a compelling argument for developing a shared purpose and can become the basis for securing more powers and change.

“ICSs are not ends in themselves – it’s about getting the best possible outcomes and having a shared focus on people who live in places, not systems.” ICB Chief Executive

“Getting everyone focused on the same ambitions takes time, hard work and a constant reminder of what you are doing and why.” Local Authority Chief Executive

Case studies: supporting populations to improve their own health

There are examples of this theme emerging across England, including:

- Can ICPs offer the opportunity to move towards more locally determined solutions that better meet the needs of communities? Lessons from South Yorkshire

- The West Midlands Combined Authority focus on improving health

- The Transport for Greater Manchester story

- Promoting the role of health in driving economic and inclusive growth in the Yorkshire and Humber region (YHealth4Growth)

Step 3: Realise everything has an impact on health

With a common view of populations and a renewed vision to better enable their health comes a much richer understanding of how working together can really deliver change. Leaders were clear they do not have to make the case for health in all policies – it is already there in strategy, in spirit and in delivery.

The challenge is to be more explicit and intentional about understanding the interactions in devolved policy, to measure and account for the health implications of all policies, and to develop collective responses to support shared populations to live healthy, prosperous lives.

“If devolution is predominantly about giving local leaders the tools to fully collaborate and make a collective difference, then this new form of system working pushes the ICS reforms further, formalising engagement structures and asking leaders to be judged together rather than individually. This is natural; the NHS is not a curtained off segment of public services after all.” Working Group Co-Chair

The roundtables agreed the need to give local leaders in ICSs and devolution areas the formal freedom and flexibility to develop their own models and priorities, rather than through the top-down national direction that many are used to. There is a challenge for local leaders to adapt to this and to share learning and work in new and expansive ways, especially during times of acute financial pressure, yet this is certainly also a challenge for Whitehall to enable this.

This third step is about the pragmatism required to make health and devolution work; understanding the added value, helping local leaders deliver services that are high quality, responsive and preventative, and pushing them into new areas of discussion where innovative solutions can be found and tested.

In particular, we found that:

- There is no one standard operating model that can fit every emerging devolution and ICS integration arrangement. We believe local leaders are best placed to determine their own approach, using a common underlying focus on strategic partner alignment and complementarity across the tiers based on mission, vision, behaviours and values.

- The need to continuously gather evidence of why local leadership best serves communities is crucial, including aligning local data and intelligence capacity with a focus on evaluation, measuring shared outcomes and the impact of health in all policies across areas with devolution deals. There are now tools available to financially quantify the public health impacts of various policy interventions.

- Securing and aligning local leadership control and accountability over the three areas of policy, investment and service specification has been seen in other sectors to result in better outcomes, including financial returns. This is a real learning point for ICS and combined authority leaders in seeking to best use their joint agency to improve population health and prosperity.

To explore the theme of ‘realising everything has an impact on health’, we looked in detail at both productivity and process.

National recommendations to realise local potential

- Government and NHS England should seek to rationalise and reduce national targets and priorities, empowering ICSs and combined authorities to identify their own through facilitating better data collection and sharing across public services.

- Government should ensure the business case and appraisal processes used by departments and national agencies supports new ways of working and embeds the financial health costs and benefits, and the wider return on investment in everyday practice.

- Government and NHS England should prioritise place-based approaches to policy, leadership development and funding, building up the joint capabilities of local ICS and Devo leaders to maximise their greater autonomy

Local priorities around which a renewed ICS-devolution partnership can focus

| Productivvity | Process |

| Support a better shared understanding of the strategic financing and funding of place. | Make mission, values and behaviours the critical local building blocks and learn from one another. |

| Change the nature of the local fiscal conversation to increase opportunities to locally attract and direct funding. | See devolution as providing the roadmap to deliver truly preventative services, linking various strategies with operational delivery. |

| Reframe the approach taken to business case appraisals and guidance development to assess the impact on health outcomes. | Collectively articulate why local decision-making is best for the health of communities and wealth of the national economy |

We discuss both these areas in more detail below.

Productivity: how we stretch the money matters

Many ICSs and devolution arrangements have been born into something of a storm. Successively tighter fiscal windows have limited their ability to address both the immediate operational issues but also to strategically plan for the future. How leaders and organisations pool their finite yet still significant resources to best affect is a vital part of working more closely, but the ICS and combined authority relationship has the opportunity to stretch its thinking way beyond.

Leaders at our roundtables repeatedly spoke of their desire to change the nature of the local fiscal conversation, challenging and supporting each other to develop and share persuasive investment propositions that could reshape their communities and their service models. This should be supported in parallel by clearer attempts from government to improve the quantity, flexibility and stability of budgets.

The productivity-related priorities that should shape future ICS and devolution working are:

1. Support a better understanding of the strategic financing and funding of place

With national financial allocations becoming smaller, more discrete and increasingly competitive, a priority for ICS and devolution leaders should be to understand better the collective strategic financing options open to them, the nature and circumstances connecting public services in urban and rural economies, and the local funding routes that can help unlock parts of the system.

Knowledge of local money flows within and between sectors is often limited, which in turn significantly reduces the ability to best use and influence the finite resources across a place; challenge existing thinking and spending where it is not fully effective; and bring in external finance partners through new whole-system plans. There has been a renewed focus on place-based public service budgets based on past programmes such as Total Place recently. Complementing a better understanding of existing financial flows should be an improved awareness of the funding pots open to places from the full range of sources, including national government, research organisations, charities and investors, and coordination and support for constituent partners in accessing and using them.

“Areas are clearly capital constrained but also revenue constrained. It’s not just about buildings and capital, it’s also about people. We do need to work on defining what an investable proposition could look like.” Director of Public Health

“Funding is typically distributed in pre-determined ways, which then operate in silos. Devolution should allow us to develop broader, shared outcomes which will naturally challenge existing money flows and enable much more effective use of them.” ICP Chair

2. Change the nature of the local fiscal conversation to increase opportunities to locally attract and direct funding

With a better understanding of local financing and funding comes the increased confidence to reframe the nature of the local fiscal conversation – stretching ICSs and combined authorities into a joint space where they understand better the externalities of their own investment and can co-develop shared objectives and outcomes. This is about having a shared business case for change, as well as shared policy and understanding, bringing an explicit focus on creating health value and maximising the economic and social return on investment from the range of health and care budgets, including not only the value that can be created elsewhere within the sector but crucially in the wider local economy.

The relationship between combined authorities and investors, for example, is an area of growing focus, and support from an ICS can be critical in helping develop investible local propositions in the population health space that will be of significant interest to private finance. This could focus on place-based investment opportunities in developing new models of care, linking local regeneration planning around housing, skills and transport with the growing prevention agenda.

“Business doesn’t want to invest where government money would be most effective. We are now much more interested in social outcomes, not just financial ones but we need to find the right type of money to meet societal need.” Investor

“We need to stretch ICS and devo leaders into a joint space where they understand the externalities of their investment, can share, hold or reallocate resources and co-develop shared outcomes.” ICB Director of Strategy

3. Reframe the approach to business case appraisals and guidance development to assess the impact on health outcomes

To embed this new way of working with private finance and partners, there is a need to accelerate the shift to value-based funding, with formal, technical business cases for investment becoming a more standardised part of developing and appraising local policy and outcomes, and thus delivering change. Further moves in HM Treasury’s Green Book to magnify the importance of social value will be important. There is a clear role for national government and agencies such as NHS England and the Office for Health Disparities (OHID) to support this, in both the government’s, and their own, development and use of broader appraisals process and guidance, but also in how they can support local partners to develop the skill set and the tools to act differently.

Given its prominence, health should be made explicitly part of future government funding, impact evaluations and policy support programmes. The data exists to make this happen, with health economic valuation tools being accepted into DLUHC appraisal processes (such as the HAUS model referenced below). What is needed is greater implementation and leadership from HM Treasury.