Key points

The NHS Confederation and CF have worked closely over the past 12 months to demonstrate the value of the NHS as an investment. To date, we have published the first national attempt at quantifying the positive relationship between increasing NHS spending, health outcomes and economic activity, and sought to understand where additional investment in a range of settings of care could deliver the most economic output.

This third report goes further still, exploring system productivity as it relates to spend. This issue is particularly timely: acute healthcare spending between 2020/21 and 2021/22 grew faster than any other form of NHS spending, despite performance continuing to be challenged with pressure on A&E, beds and discharges. Responding to these pressures requires a more holistic understanding of system productivity.

Our earlier reports demonstrated the important role primary and community care play in creating health value. For the purposes of this report, we have performed a deep dive into community care given the general ambiguity surrounding the services that make up this NHS setting, its broad links with other parts of the system and the wider economy, and what we believe to be significant potential to unlock significant system productivity gains.

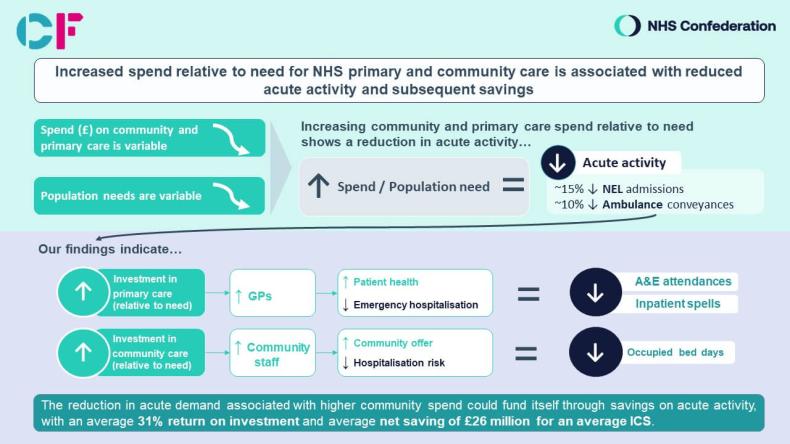

Our analysis found: 1) Those areas that spent relatively less on community care in terms of population need have seen higher-than-average levels of hospital and emergency activity, compared to those spending relatively more. On average, systems that invested more in community care saw 15 per cent lower non-elective admission rates and 10 per cent lower ambulance conveyance rates, both statistically significant differences, together with lower average activity for elective admissions and A&E attendances.

2) Despite the increased focus on creating better health value and unlocking system productivity, there is currently no relationship between the amount invested by NHS organisations in community care and their population community care needs. The sheer variation in spend perhaps highlights a wider lack of understanding and prioritisation in community care.

3) The reduction in acute demand associated with this higher community spend could fund itself through savings on acute activity if a causal relationship were assumed, with an average 31 per cent return on investment and average net saving of £26 million for an average-sized integrated care system (ICS), exemplifying the power and potential of community care at a system level.

Each of these findings deserve attention and lead us to make a series of recommendations for national government, NHS England and ICS leaders that can collectively help create community health value and unlock the power of health well beyond the hospital.

Overall, we recommend that community spend is prioritised as a mechanism for reducing long-term pressure on the acute sector, as a crucial contributor to healthcare system productivity and as a direct lever to provide patients with the care they deserve. Improving impact tracking is also critical, and we recommend that providers of community health services work with their ICSs to report operational performance and data to ensure impact is adequately understood.

The report points to a wider challenge for community care. Given community needs are calculated nationally, it follows that certain findings and recommendations are relevant for national bodies, such as government and NHS England. However, since there is no national contract for community services, community spend is almost entirely at the discretion of local leaders. This analysis should equip leaders with the necessary focus, information and evidence base to navigate challenging decisions about how to allocate resources, making significant strides in evolving toward a more preventative system that is effective both in terms of cost and care.

Given this analysis, we strongly believe that community care can play a significant role in supporting system productivity and can provide ICS and NHS leaders with a direct lever of control that they can shape and use to deliver change.

To help leaders to put theory into practice, we have included a case study encompassing the five legacy CCGs that now make up North Central London (NCL) ICS. The place-specific example illustrates a need to streamline inconsistent service offers and develop a clearer community care offer for the wider system. It also provides tangible steps that systems can take to realise these ambitions, namely understanding the existing services, developing a refined offer, creating a means to track impact and building a plan for practical implementation.

Background

Shifting more care out of hospital and into the community was one of the key improvements outlined in the NHS Long Term Plan. While government health expenditure has continued to rise nearly five years on, the NHS’s spend on acute care has grown faster than any other area, increasing in real terms by £10 billion (17 per cent) between 2020/21 and 2021/22, now accounting for over half (53 per cent) of total system spend (see Figure 1). Despite increased resources and prioritisation across the acute sector, A&E pressures have not ebbed and overall performance continues to face challenges.

With the sector working to cultivate system-wide resilience, particularly as winter approaches, there is an opportunity to revisit the goals outlined in the Long Term Plan and accelerate the shift to a sustainable, preventative model. A model that not only views prevention [ 1 ] through the lens of reducing hospital and emergency demand, but also better responds to the needs of the population it serves; a model that is good for the nation’s health and the wider economy.

Figure 1: National clinical commissioning group spend by setting of care, 2022 real terms

Creating health value

This report demonstrates that there is a substantial opportunity to improve system productivity by investing in community care, which can unlock benefits for local citizens and the broader economy. Our analysis suggests that such a shift could save the typical-sized integrated care system (ICS) around £26 million in reduced acute demand alone, in addition to the vital and wider positive economic footprint that our earlier work has shown healthy populations engender.

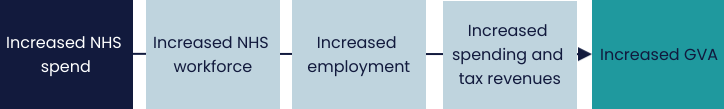

Community care is vitally important in its own right. But by investing in upstream, preventative care, a system has greater capacity to treat patients earlier in the pathway, which ultimately mitigates the likelihood that they will become acutely unwell and require more costly care. By improving health and avoiding time in hospital, individuals will be more productive, which contributes to a larger and more effective workforce (including within the NHS itself) and increased consumer spending and tax revenues, which collectively contribute to wider economic growth overall.

There are two potential mechanisms through which NHS spend increases local gross value added (GVA):

These interconnections reflect the need to view the work undertaken in this report through the wider prism of our Value in Health programme, the overarching intention of which is to study the links between health and the economy and to underscore health investment as an explicit tool of economic development.

From Safety Net to Springboard: Putting Health at the Heart of Economic Growth and Creating Better Health Value have shifted public rhetoric surrounding health spend, from one of drainage and deficit to a focal asset to be invested in and capitalised upon. The former was the first national attempt to establish a quantifiable relationship between NHS investment and wider economic growth. The latter delved into this investment to determine where the pound was most effectively spent and evidenced what had long been suspected: increased resources are most wisely and effectively invested upstream, with a particular focus on primary and community care. These two settings of care continue to challenge and excite our thinking.

Community care in focus

In the aforementioned reports, we identified a link between increasing the primary care workforce and a subsequent decrease in acute utilisation and boost in economic activity. We also highlighted the significant potential economic return on investment from investing in primary and community care.

For this third report, we have focused on community care as we believe there is a level of perplexity surrounding the services provided in this NHS setting and its broad links with other parts of the system and the wider economy. Our intentions here are thus threefold:

- illustrate the power of this vital asset for local communities and the economy

- map out a process that provides local leaders with the knowledge, insight and tools necessary to fully unlock its potential

- broaden understandings of prevention beyond its implications for the acute setting to focus on wider system productivity and better population health outcomes.

Methodology and definitions

To understand how community spend influenced acute activity, we compared the differences in acute activity levels for two groups of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs)*: one of which spent relatively more on community care and one which spent relatively less. This enabled us to understand how differences in community spend related to differences in acute spend. Our full methodology can be found in the appendix.

For the purposes of this report, we looked at historical CCG spending allocations and based our definition of community care on NHS England’s 2019/20 to 2023/24 revenue allocations:

“Community services are CCG-funded health services which take place outside of a hospital setting and are not part of the primary medical care portfolio. Community services cover a wide range of service types and different CCGs will commission different sets of services depending on the make-up of their populations and on historical factors affecting service provision in their area.”

* In this report we examined spending by CCG, the unit by which NHS spend data is routinely available.

Chapter footnotes

- 1. Given the range of services community care encompasses, for the purposes of this report, prevention can include primary, secondary or tertiary care, depending on the context. (For example: health visiting advice in primary care; wellbeing services in secondary care; and diabetes care in tertiary care). ↑

Scratching beneath the surface: what we found

Our analysis of community spending and system productivity found that:

- Those areas that spent relatively less on community care in terms of population need have seen higher average levels of hospital and emergency activity, compared to those that spent relatively more. On average, systems that invested more in community care saw 15 per cent lower non-elective admission rates and 10 per cent lower ambulance conveyance rates – both statistically significant differences – together with lower average activity for elective admissions and A&E attendances.

- Despite the increased focus on creating better health value and unlocking system productivity, there is currently no relationship between the amount invested by NHS organisations in community care and their population community care needs. The sheer variation in spend perhaps highlights a wider lack of understanding and prioritisation in community care.

- The reduction in acute demand associated with this higher community spend could fund itself through savings on acute activity if a causal relationship were assumed, with an average 31 per cent return on investment and average net saving of £26 million for an average-sized ICS, exemplifying the power and potential of community care at a system level.

For health beyond the hospital to become a more recognised part of system thinking, it is important that we explore these findings as well as their implications in more detail.

© Carnall Farrar

Measuring community spend against community needs – the starting point to improve system productivity

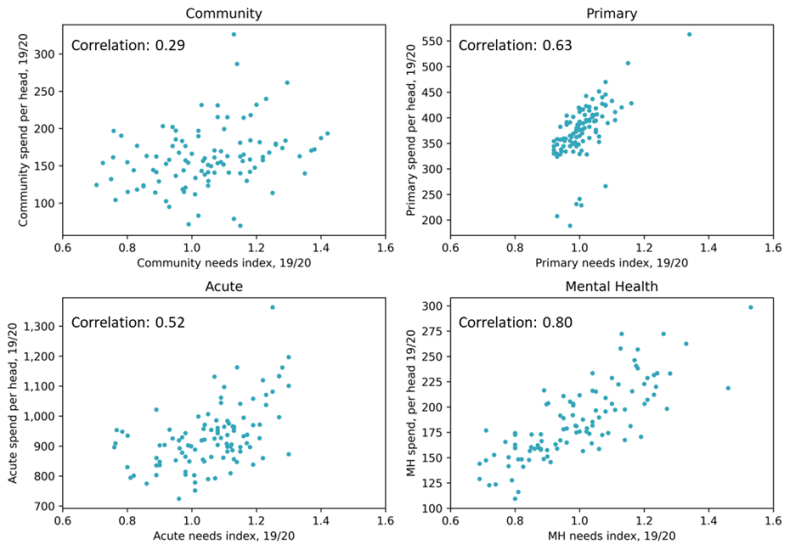

NHS funding is allocated using a needs index that captures the amount of care needed in a local population. Actual spending on community care would be expected to correlate with the population need as calculated by the needs index, however, we found this not to be the case. Figure 2 reflects the correlation between NHS spending by setting and the corresponding needs indices, as released by NHS England.

While a positive correlation was found for primary, acute and mental health care settings, indicating a correlation between spend and expected need, this was not the case for community care. This lack of correlation is unique to community care spend and highlights the sheer variation in care that patients receive across England.

Figure 2: Community spending does not correlate with community needs index, in 2019/20 data

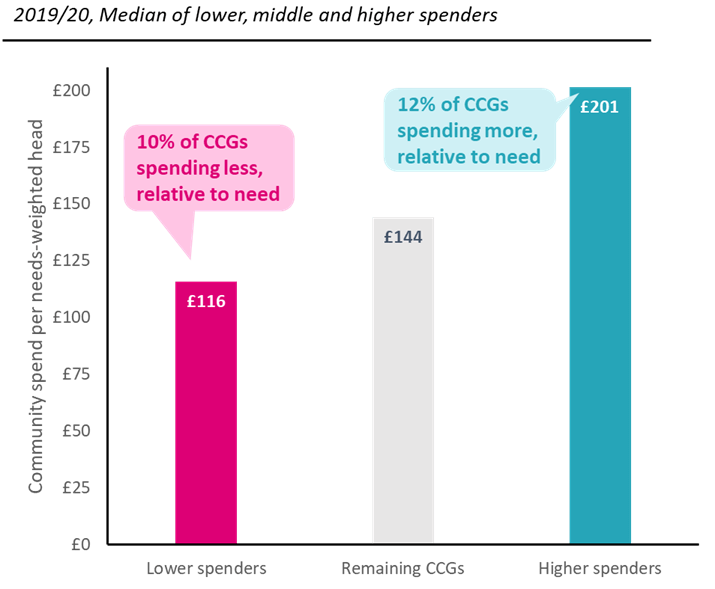

Figure 3 illustrates lower-spending CCGs (the pink bar) and higher-spending CCGs (blue bar) per head on community care, weighting for population need. As explored in the methodology, higher-spending CCGs were classified as those with spending levels one decile above the national median and population needs one decile below the national median, while lower spending CCGs were those with spending levels one decile below the national median and population needs one decile above the national median.

Figure 3: CCG classifications based on spending compared to needs index

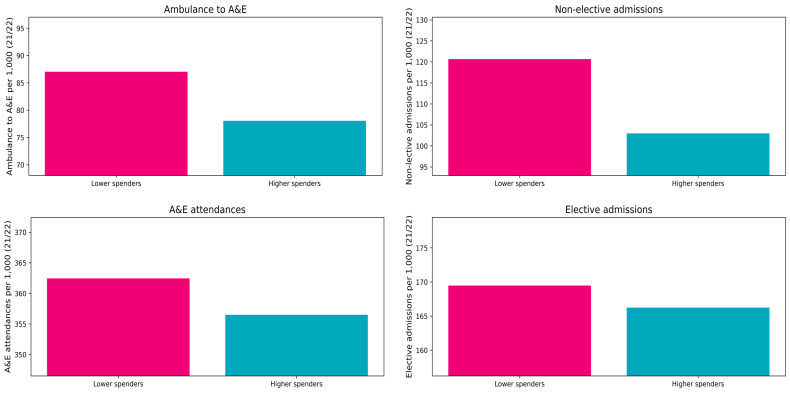

To understand our analysis and findings, we wanted to compare those that spent the most and the least with the associated local acute spend. Figure 4 highlights the range across four categories: ambulance to A&E; A&E attendances; non-elective admissions; and elective admissions. While factors other than relative community care spending may contribute to the acute activity seen, we found statistically significant differences in non-elective admissions and ambulance conveyances, with 15 per cent and 10 per cent average differences respectively.

This suggests that neglecting community care services may be a false economy, as patient health may deteriorate and subsequently require more expensive and disruptive care in hospital. We estimate that there is a substantial potential saving associated with higher community care spending in terms of hospital care prevention, averaging £25.6 million saving [ 2 ] per year for a typical-sized ICS, as reflected in figure 4.

Figure 4: Reducing acute demand by increased community spending would be self-funding, with 31 per cent return on investment in acute care savings

How interventions in primary and community care can improve system productivity by reducing acute demand

From Safety Net to Springboard identified a more explicit relationship between an increase in the primary care workforce and a decrease in acute utilisation. The analysis demonstrated that investing in more GPs per head leads to reductions in both A&E attendances and long-stay non-elective inpatient spells. In addition to substantial savings from hospital care, [

3

] reduced A&E attendances and lower rates of long-term sickness were again associated with an increase in the employment rate and growth in the economic activity.

Our second report, Creating Better Health Value, demonstrated that primary and community care alike could produce £14 in economic growth for every additional pound spent. Given the equal potential gross value added (GVA) of both primary and community care, we endeavoured to find an analogous inner-system relationship between investment in community care and reduced acute pressure to that established between primary and acute care in the prior report.

Community and primary care services have the benefit of reducing the burden on hospital services through reduced A&E attendances and admissions, faster discharge and shorter length of stay. A strategic investment in these areas can therefore mean optimised healthcare delivery ensuring better health outcomes in general through better care offered at the right place and the right time.

Chapter footnotes

- 2. The true saving would likely be higher, given patients requiring acute care are more likely to involve ongoing hospital contact and less likely to be economically productive, as referenced in this report. ↑

- 3. The analysis specifically found that the impact of adding one GP for 10,000 people equates to an estimated reduction in cost to be £82,071, relative to need. The monetary impact is significantly greater than this direct saving, given wider economic benefits. ↑

An untapped resource?

While reduced acute demand and the associated savings alone provide a compelling case to rethink investment in community care services, the true value lies beyond unrealised system savings. Leaders must also be equipped with the insight and data to balance competing demands within a complex operating system, and national policymakers should attempt to better understand the barriers local leaders might face.

One potential explanation for the misalignment in community care spend and need could be related to the scale of this particular NHS care setting. The vast range of services offered, the multitude of approaches taken and the varied partnerships and settings used require real and nuanced understanding to maximise their reach.

Community care is delivered by a range of organisations, including community interest companies (CICs), which deliver NHS services; standalone community health services; and integrated trusts, which deliver community services alongside other types of care. Community care includes adult community services (such as district nursing), children’s services (such as school visitors), health and wellbeing services (such as smoking cessation), specialist long-term condition management (such as diabetes care), planned community services (such as podiatry), and hospital services (such as bedded treatment for rehabilitation).

The purpose, effectiveness, volume, level of investment and range of community services vary substantially across local areas. These complex patterns of service provision represent a unique strength for communities and the wider economy but also contribute to an overarching lack of understanding at both national and local levels.

To improve the understanding of community services at a national and local level, we highlight four key areas in which further investigation could harness community care’s potential. The implications these improvement measures hold for a variety of national and local leaders are outlined in the recommendations section of this report, and their practical application is exemplified in the case study on North Central London ICS.

- Generate methods to capture data that better informs community services’ funding, spending, demand, activity, availability, quality and impact.

- Compare findings from the above data analysis to determine whether national community needs indices appropriately represent the locality.

- Develop a comprehensive inventory of community care services that exist on the ground.

- Reassess whether the community care services on the ground adequately address need and determine where gaps could be filled in the service design.

Putting theory into practice: the North Central London story

Recently, CF supported North Central London (NCL) ICS to perform a strategic review of existing community care services in the area, and to develop a bespoke community service offer. This core offer streamlined services to create more consistency in care throughout the system, addressing inconsistencies in service offer, access and outcomes, and focusing on delivering consistent, equitable and high-quality community services for residents.

What the system faced

CF analysis found that historic funding differences across the CCGs that previously made up the ICS had led to considerable variation in the way community services were commissioned and delivered across NCL. This resulted in substantial variation in service offers, with inconsistent waiting times and inequalities of outcomes across the five boroughs.

For example:

- Islington had five times as many children’s community nursing staff as Barnet and was the only borough offering a hospital at home service for seriously unwell children.

- Enfield had over twice the prevalence of diabetes as Camden yet had a community diabetes resource less than half the size.

What the system did

System leaders across NCL agreed that the level of variation needed to be addressed as a priority and launched a multi-year programme to create a core offer for all residents.

Working closely with NCL ICS, CF co-developed a consistent community services core offer for the system, producing a set of priorities with care functions detailed in a set of specifications, as well as a set of coordinating functions encompassing a central point of access and case management.

The core offer describes the services that should be universally available to all NCL residents, with consistent:

- response times

- criteria for people to access services

- requirements for services to meet national ‘must-dos’

- workforce capabilities required.

Results and benefits

NCL ICS has committed to providing the universal core offer and has already agreed to a number of significant investments to harmonise community services across the five boroughs, including:

- £5.4 million investment in virtual wards, expected to avoid 13,000 bed days annually

- £1.95 million in interventions in Enfield in the first year, expected to avoid more than 2,000 bed days annually

- £1.45 million in interventions Haringey in the first year, expected to avoid more than 500 bed days annually.

Viewpoint and recommendations

This report has reflected the important role community care plays in keeping people well and reducing acute pressures. While there has been an increased focus on community care in recent years, the true value has not yet been realised. In this challenging financial environment, we believe it would be a mistake to undervalue preventative services.

Given the role and ability of local leaders to directly commission and design services within the community, there is a clear opportunity for systems to take an asset-based approach to delivering on their four key purposes, using community care as the very foundation for a new method to supporting people to live healthy, prosperous lives.

As such, we make the following recommendations:

National government

- In future policies, working groups or committees and funding schemes, future government policy should recognise the interrelatedness of community care with other services outside of the direct remit of the Department of Health and Social Care, such as between health and education or health and work, by working more formally across departments. These links are critical in supporting lives and livelihoods yet are often misunderstood in siloed policy development.

- To support additional investment in community care, government should allow for a minimum of two years of double running, given our findings account for a lag of two years in assessing the impact of community spend on acute activity to allow the effects of increased community capacity to be felt. This points to a wider recommendation that government should acknowledge that as systems shift to an emphasis on more preventative, upstream care, the return on investment will not be immediate.

- Investment in community care in particular should be incentivised, including through appropriate payment mechanisms, as a means for reducing long-term pressure on the acute sector as winter approaches, including through developing approaches to tackle the community backlog in a similar way to the elective one.

NHS England

- NHS England should work with local leaders to develop a clearer definition of community care, including what it is, what services fall under its purview, and where there are gaps between statutory and non-statutory services.

- NHS England should work with clinical system providers to:

- prioritise data that better informs the value of community services, including its funding, spending, demand, activity, availability, access, quality and impact

- incentivise local leaders to collect comprehensive and accurate data – this data should be leveraged to equip local leaders with the tools needed to develop a holistic view of what is happening on the ground already and where gaps exist

- standardise the collection of community care data and definitions.

- In future policies, NHS England should recognise the benefits of the NHS investing more in the community sector, including keeping people well at home and in community settings close to home, supporting people to live independently, and ultimately reallocating pressures throughout the system. Funding allocations should reflect this understanding and an overarching will to prioritise preventative care.

- NHS England should conduct more data-led analysis of initiatives to demonstrate the impact and recognise the potential to prevent admissions in the future and the longer-term return on investment. Virtual wards and urgent community response services, for instance, have the potential to offer further reductions in spend in the future, and this impact should be diligently recorded.

Integrated care systems

System leaders are encouraged to use this report to:

- review community care spending against need at a system level, understanding the nature of associated acute savings that can be unlocked locally

- develop a comprehensive inventory of local community care services and their complementarity to other settings of care

- understand the specific role of community services in improving wider local system productivity

- help broaden their understanding of prevention and deliver on the recommendations set out in the Hewitt review.

Creating health value: a golden thread

An effective model of community care that keeps people well for longer and promotes a good quality of life that ultimately contributes to prosperous economies underscores the four key purposes of integrated care systems. This report, alongside its predecessors, has sought to explore how creating health value can help system leaders deliver against all of them. To ensure we continue to view community care through this broader system prism, we have highlighted below how the findings in this report might best relate to the four key purposes of an ICS:

- Improving population health and healthcare: The diversity, settings and combinations of community care services enable a more flexible and rounded approach to health – bringing together a myriad of community partners, including voluntary, community and social enterprise and private sector organisations, all focused on collectively addressing the wider determinants of health.

- Tackling unequal outcomes and access: Given the diverse and extensive range of care offerings, community care is designed to meet the needs of those who may not be able to access care in more traditional settings, including patients for whom the NHS often struggles to reach. As the North Central London case study illustrates, the development of a core community care offer can streamline services, creating more reliability in care throughout the system and addressing inconsistencies in service access and outcomes.

- Enhancing productivity and value for money: The analysis in this report estimated significant potential savings for a typical-sized ICS associated with increased community care spending.

- Helping the NHS to support broader social and economic development: In addition to cost savings from hospital care prevention, community care has an important enabling role in stimulating the wider economy – including supporting a more productive workforce and boosting wider employment, spending and tax revenues.

Supporting members to truly shift on prevention

The NHS Confederation and CF are working closely to help leaders understand, narrate and evidence their approaches to system change and will be continuing to build up a suite of products in the coming months that will collectively help shift the dial. We look forward to supporting members to truly shift on prevention.

Further information

Our Health Economic Partnerships work programme supports the NHS to understand its growing role in the local economy and to develop anchor strategies at institutional, place and system level. Visit www.nhsconfed.org/topic/health-economic-partnerships or contact Michael Wood and Bridget Gorham for more information.

Appendix: Methodology

To understand how community spend influenced acute activity, we compared the differences in acute activity levels for two groups of CCGs*: one of which spent relatively more on community care and one which spent relatively less. This enabled us to understand how differences in community spend related to differences in acute spend.

Acute activity CCG community spend, High / NWH Δ Acute activity CCG community spend, Low / NWH

Our first step was to define the two separate sets of CCGs: those which, in 2019/20, spent more on community care per needs-weighted head (NWH), and those which spent less per NWH. This allowed us to compare differences in spend between diverse areas. Higher spending CCGs were defined as those with spending levels per NWH one decile above the national median and population needs one decile below the national median in the financial year 2019/20. Lower spending CCGs were defined as those with spending levels one decile below the national median and population needs one decile above the national median.

‘Need’ was determined by an index relative to the national average, and accounts for a number of factors including population demographics, prevalence data and the level of historic provision. The registered CCG population is multiplied by the needs index to calculate a needs-weighted population: where calculated need is greater than average, the weighted population is greater than the registered population, and vice versa. Using the needs-weighted population to calculate spend allows us to compare CCGs that face very different challenges.

Having established two peer groups, we compared the level of acute activity per head between the two groups. We have assumed a lag of two years in assessing the impact of community spend on acute activity to allow the effects of increased community capacity to be felt, meaning we used 2021/22 data. Our acute data was pulled from the hospital episode statistics (HES) dataset and counted per 1,000 population. We assessed:

- non-elective admissions

- elective admissions

- emergency attendances

- ambulance conveyances to A&E.

We found that on average, areas that invested more in community care saw 15 per cent lower non-elective admission rates and 10 per cent lower ambulance conveyance rates, both statistically significant differences, together with lower average activity for elective admissions and A&E attendances. Having established that there was a statistically significant difference between acute activity in high and low spending CCGs, we assessed the level of cost associated with this activity.

*In this report we examined spending by CCG, the unit by which NHS spend data is routinely available.

Figure 5: Areas that spent less on community care relative to need saw higher average levels of acute activity

To calculate the level of cost, we multiplied the previously established acute activity counts by the published averaged unit costs for delivering treatment, as found in the national schedule for NHS costs. Average savings were estimated as the difference of mean acute costs between higher and lower spending CCGs. To provide this analysis at a system level, we multiplied the per head costs, in both high and low spending CCGs, by the average-sized ICS population size in the appropriate year. The net saving for the typical-sized ICS was then estimated as the difference between the total cost for high and low spending ICSs.

x̄ Acute spend Community spend high / NWH Δ x̄ Acute spend community spend low / NWH

Finally, to estimate the return on investment associated with community care, we used both the saving available, as calculated, and the difference in mean community spending for the higher and lower spending areas.