Key points

Commissioning is how integrated care boards (ICBs) and their partners ensure £164 billion of public money (19 per cent of public sector spending in England) is best used to improve health. Although commissioning is further away from patients’ eyes than provision of care, it determines what services are delivered, by whom, for whom, where and why.

The Secretary of State has tasked ICBs to be ‘pioneers of reform’ through ‘strategic commissioning’, driving the three shifts for health services: from hospital to community, from illness to prevention and from analogue to digital. This is to help the NHS better manage rising demand for services without consuming an ever-growing share of national wealth.

Current commissioning arrangements can often involve transactional contracting with individual providers. For ICBs and their partners to pioneer this reform, commissioning needs to evolve. This is essential to putting the NHS on a sustainable financial and service footing.

This report, commissioned by NHS England and developed independently by the NHS Confederation, is based on engagement with ICS leaders and system partners. It seeks further understanding of what strategic commissioning is and proposes six shifts in the approach to commissioning that ICSs need to make to drive public service reform and ensure a sustainable health and care system for the future:

1. Reactive to proactive – pushing beyond reactive service management to keeping people healthy by better understanding and then proactively addressing populations’ health needs.

2. Downstream to upstream – shifting a greater share of resources from downstream acute services to anticipatory interventions in the community and better support for longer-term and complex conditions.

3. Competition to collaboration – replacing organisational silos with genuine partnerships across local government, the VCSE sector and the breadth of the NHS.

4. Transactional to transformational– moving beyond just managing contracts for episodes of care to transforming services and commissioning pathways for population cohorts in partnership with providers and the public.

5. Cost to value – achieving return on investments, not just managing costs.

6. Compliance to leadership – empowering local leaders to lead, innovate and listen, rather than just look upwards for instruction.

The transition to strategic commissioning will require a phased implementation process and rely on developing the right skills and capabilities for both individuals and organisations. This includes developing diplomatic and data analysis skills and supporting system leadership.

NHS England’s forthcoming strategic commissioning framework should reflect the principles and proposals outlined in this report and be accompanied by an implementation plan to drive change. Form must follow function. The announced 50 per cent cut to ICBs’ running and programme costs must be carefully managed to ensure they are able to deliver on the government’s ambitions for transformation and risks slowing down the move towards strategic commissioning.

This report also sets out recommendations for a phased implementation process.

Outlining a new vision for strategic commissioning that will enable ICBs to be pioneers of reform, and the skills and capabilities needed to fulfil their statutory duties and their wider role in driving and sustaining transformation in health and care.

Six shifts to achieving strategic commissioning

- Reactive to proactive – pushing beyond reactive service management to keeping people healthy by better understanding and then proactively addressing populations’ health needs. This requires ICBs to improve quantitative data analysis capability by harnessing digital technology and to utilise local partners’ and communities’ qualitative insights to improve service design and understand need.

- Downstream to upstream – shifting a greater share of resources from downstream acute services to anticipatory interventions in the community and better support for longer-term and complex conditions. This requires changes to pathways’ design, Integrated Neighbourhood Teams to help deliver anticipatory interventions, and new contractual payment mechanisms to shift resources.

- Competition to collaboration – replacing organisational silos with genuine partnerships across local government, the VCSE sector and the breadth of the NHS. Care should be wrapped around patients, rather than passing them between different providers. This requires collective resource management, shared accountability and an integrated workforce.

- Transactional to transformational – moving beyond just managing contracts for episodes of care to transforming services in partnership with providers and the public. Commissioning whole pathways for population cohorts should become the norm. This requires robust change management capabilities and joint decision-making through effective governance.

- Cost to value – achieving return on investments, not just managing costs. This requires moving from just activity-based contracts to population outcome measures and multi-year planning.

- Compliance to leadership – empowering local leaders to lead, innovate and listen, rather than just look upwards for instruction. This requires fewer national targets (focused on what, not how), new system leadership capabilities and learning networks which help take the best of the NHS to the rest of the NHS.

Recommendations for phased implementation

Phase 1: Setting out the vision and establishing support infrastructure (0-6 months)

The ten-year health plan in late spring 2025 will set out a roadmap for change and articulate a clearer vision for neighbourhood health. NHS England’s forthcoming strategic commissioning framework should reflect the principles and proposals outlined in this report and be accompanied by an implementation plan to drive change. NHS England should establish the structures needed to support transformation and development of skills and capabilities. This includes a national commissioning forum to support and enable peer learning.

Phase 2: Reforming planning and performance systems (6-12 months)

Reform core processes to support strategic commissioning. This includes redesigning annual planning processes around population outcomes, developing new templates and methodologies for pathway-based commissioning, and creating frameworks for measuring progress on system integration. Early adopter systems can demonstrate how these reforms will drive meaningful change in practice. Systems will need advanced analytical capabilities and standardised tools to strengthen population health management.

Phase 3: Implementing new ways of working (12-24 months)

Resource and roll out pathway-based commissioning models, establish new financial arrangements for risk sharing and create integrated data systems for real-time monitoring. Success depends on balancing the pace of change with maintaining service stability.

Phase 4: Embedding cultural change (Ongoing)

Embed sustainable improvement through learning networks, peer review processes, and formal mechanisms for adopting successful approaches. This cultural transformation represents the most challenging aspect of change, requiring sustained commitment across all levels to create lasting improvements in how systems work together

Introduction

Integrated care boards (ICBs) are stewards of £164 billion of revenue spent on NHS services, which is some 19 per cent of all public sector spending in England and roughly equivalent to the gross domestic product of Slovakia 1 . In the aftermath of COVID-19 and with demand outstripping the rate of economic growth, pressure on local services has never been so great. Too much public money is still being deployed to meet the challenges of a previous era. Commissioning is the process by which this money is spent to determine what health services are delivered, by whom, for whom and where. A more strategic approach to commissioning is required to fix the foundations of health and social care. This should build on the establishment of integrated care systems (ICSs), which aim to promote collaboration and the integration of services.

The Secretary of State declared ICBs to be the ‘pioneers of reform’, tasked with ‘lead[ing] the transformation of care’ through strategic commissioning of services and the development of a new neighbourhood health service. To do so, ICBs must be not just purchasers of care from providers, but the drivers of public service reform, the guardians of taxpayers' money, and champions of patients' and residents' interests.

This report, commissioned by NHS England and produced independently by the NHS Confederation, draws on a series of roundtable discussions with leaders and staff working in ICBs and across systems more broadly 2 . It describes a new vision for strategic commissioning, explains how it differs from the model that has come before, and identifies the changes needed to bridge that gap. It also highlights the skills and capabilities ICBs and their partners will need to fulfil their statutory duties and their wider role in driving and sustaining transformation in health and care.

You can read more about our vision for strategic commissioning in our summary: Strategic Commissioning: What Does It Mean?

Chapter footnotes

- 1. See Appendix A for calculation details. This is 81 per cent of NHS England’s revenue and capital spending for 2025/26. ↑

- 2. This includes engagement with (but not limited to) ICB chairs and chief executives, ICP chairs, local government leaders, ICB chief people officers, ICB directors of strategy, ICB director of primary care, and ambulance trust chief executives. ↑

The case for change

Learning from the past

Following the purchaser-provider split in 1990, the early days of NHS commissioning were focused on increasing choice and tackling organisational inertia, which proved difficult to achieve. Separating commissioning from provision aimed to emphasise planning and allocating resources to meet population health needs.

Primary care trusts (PCTs), which operated as commissioning organisations between 2001 and 2013, demonstrated the benefits of working at scale. In some areas, PCTs achieved remarkable success by pooling expertise and resources, providing early examples of integrated working. These efforts showcased the potential of partnerships to address shared challenges and improve the public’s health.

However, PCTs often lacked formal mechanisms to align incentives and share risk across organisational boundaries, while separate accountability frameworks encouraged organisations to prioritise individual targets over system outcomes. This siloed approach ultimately constrained their ability to make change happen, as they were not able to coordinate action across the entire patient pathway.

Initiatives such as World Class Commissioning sought to make commissioning a highly skilled and outcomes-focused process. It introduced useful frameworks and methodologies but produced mixed results, highlighting the difficulty of nurturing new skills and capabilities without universal and sustained commitment to cultural change.

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) followed, after the Health and Care Act 2012. With clinical leadership on CCG boards, clinicians and managers developed strong partnerships that facilitated efforts to drive quality improvement. CCGs' boundaries and scale – co-terminous with local authorities – facilitated some integrated commissioning and provision of health and social care at the place level, using Section 75 agreements and structural integration through joint posts and committees.

CCGs began to develop some of the behaviours required for strategic commissioning. Despite the initial intention of the 2012 Act to increase competition, a pivot from competition to collaboration gradually emerged, first through sustainability and transformation partnerships, then non-statutory ICSs. Many CCGs had begun to take on the role of system convenor, managing competing provider interests and funding requests and looking to act in the interests of the whole population. However, their small scale inhibited this (regional providers, such as ambulance trusts, would have to work with up to 33 CCGs).

The Darzi review highlighted many valid drawbacks of the CCG model. But there were also three main benefits that ICBs inherited:

- Empowerment of clinical leadership and engagement.

- Driving quality improvement.

- Facilitation of place-based integration.

This CCG legacy has, in some ways, set up ICBs well for the task of evolving how they commission. That said, the transition from CCGs to ICBs did, at least in the short-term, set back integration in some areas by unpicking good working relationships and pooled budgets at place level between CCGs and local authorities following the 2022 Act. ICSs are continuing to develop place-based leadership and devolve decision-making within systems. However, by ICS leaders’ own admission, the pace of devolution to place is slower than they have liked due to wider system pressures.

Today's reality: recent changes in commissioning policy

ICSs were ‘born into a storm’ in the wake of COVID-19 and austerity. The new structures require effective system working with providers remaining as sovereign organisations, albeit acquiring a new duty to have regard to the wider effect of their decisions and a duty to collaborate. ICSs extend beyond the 42 ICBs at their heart. Alongside each ICB are many other system partners, notably:

- local government

- NHS trusts and foundation trusts

- primary care providers

- social care providers

- the voluntary community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector

- universities and other public sector bodies

- other private sector partners.

Many of these partners come together to provide the strategic direction for the system through the integrated care partnership (ICP). ICBs and ICPs together acquired four core purposes. These are to:

- improve outcomes in population health and healthcare

- tackle inequalities in outcomes, experience and access

- enhance productivity and value for money

- help the NHS support broader social and economic development 3 .

ICBs inherited most of their staff from CCGs, despite a different skill set being required in many areas. Only the most senior figures within ICBs (NEDs and board-level executives) were newly recruited. Some of these individuals transferred from CCGs, but others originated from elsewhere. Recruitment of new board-level leadership does not necessarily change culture and ways of working. Many ICB staff have moved across from the previous CCGs without the necessary development support to understand and adopt the new ways of working required for ICSs to succeed. Staff within ICBs, providers and across systems more widely need to shift attitudes and behaviours to achieve system working.

The delegation of additional commissioning responsibilities gives ICBs end-to-end commissioning of most care pathways, providing an opportunity to improve integration of care, access to services and help deliver care closer to home. The Darzi review highlighted the fragmentation of healthcare services resulting from the Health and Care Act 2012. As ICBs work at a larger footprint with a larger patient population, they can take on new functions previously sub-scale. Since 2022, NHS England is delegating several areas of commissioning to ICBs. This includes delegation of primary medical services, pharmacy, optometry and dental (POD) services, while the delegation of specialised service commissioning is underway, and vaccinations and screening commissioning responsibility will be transferred on 1 April 2026. This enables a wider change from commissioning individual providers to pathways of care, improving patient experience and delivering best value from available budgets.

Meanwhile, the operating environment for ICBs grows more challenging by the day. A 30 per cent reduction in Running Cost Allowance has forced organisational restructures, stretching leadership capacity and head space just as the agenda grows more complex. Place partnerships – crucial to delivering integrated care – are developing at markedly different speeds across the country, creating an uneven foundation for change.

Service and financial pressures are also making true collaboration harder. Despite the rhetoric of system working, block contracts and separate organisational budgets reinforce institutional boundaries. When targets and money present challenges, organisations understandably focus on their own imperatives rather than system priorities. This makes strategic commissioning more important than ever, but also more difficult to achieve. ICBs must work with their partners to drive transformation while tackling immediate pressures.

Transforming our health and care system

NHS contracting arrangements were designed originally to wrap around existing provider architecture and organisations’ baseline budgets, rather than around patients. Delivering the government’s reform agenda of three shifts – from hospital to community, from illness to prevention and from analogue to digital – requires changing commissioning. A new approach to commissioning and development of commissioning skills and expertise can help get patients the right care, at the right time in the right place, improving patients’ outcomes and experience. This includes shifting resources towards earlier intervention.

Provision of health and care is still too fragmented, to the detriment of patients’ outcomes and experiences. This fragmentation is reinforced by the many different funding streams that feed into the complex mosaic of statutory provision. Joining up these services is particularly important as more people are expected to be living with major illness and managing multiple long-term conditions, partly due to an ageing population. If real transformation and integration of services is to be accomplished, all partners must collaborate to make best use of their collective resource and improve patient care outcomes.

The cost of inaction is high; the public deserve a health and care system that is there for them in their time of need and contributes to the health and wealth of the nation. Strategic commissioning is at the heart of the transformation needed and must take a different starting point: the needs of populations, designing and commissioning services around the support and interventions residents require.

Chapter footnotes

- 3. ICS Design Framework, p. 3 ↑

Tomorrow’s vision: six shifts to strategic commissioning

Based on engagement with ICS leaders, the NHS Confederation proposes six shifts in behaviour that ICSs need to make to drive public service reform and ensure a sustainable health and care system for the future. NHS England’s forthcoming strategic commissioning framework provides an opportunity to set out detail and should align with the forthcoming ten-year plan for health, the NHS England operating model and other national policies to deliver this vision.

Our members see these shifts as key components of the wider cultural changes needed in the years ahead. As systems mature, these shifts will help move them towards a model of designing and commissioning services around population cohorts.

1. From reactive to proactive

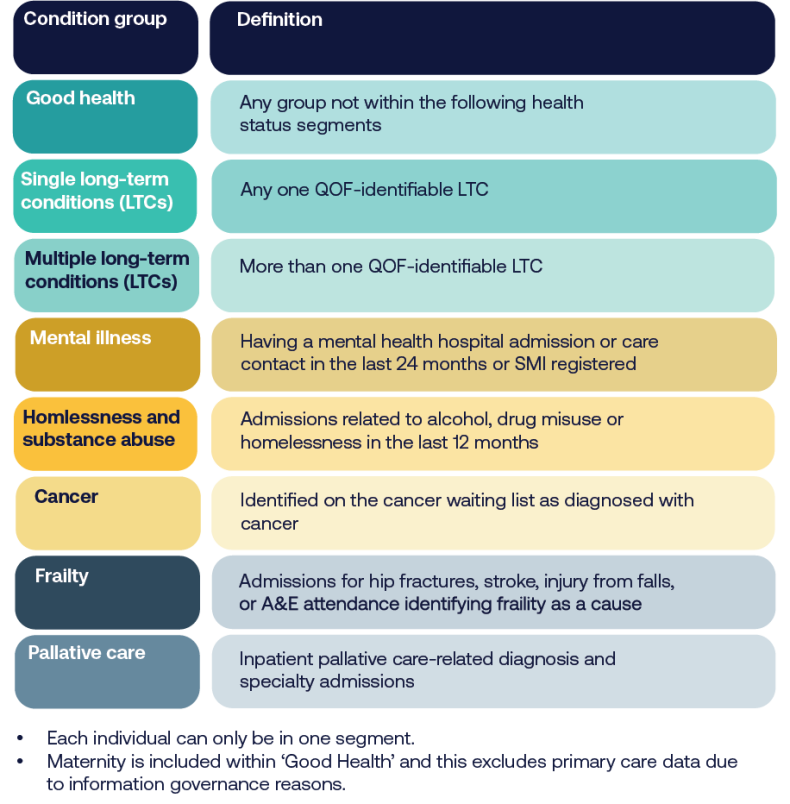

The future of NHS commissioning must shift from managing demand to addressing the underlying needs of the population, tackling what Paul Corrigan described as the ‘curve of doom’: a widening gap between the growth in demand and provider capacity to supply care services. This transition requires moving beyond a reactive focus on pressures at the NHS ‘front door’ and instead embracing a more proactive and strategic approach. By using population segmentation to uncover hidden needs and opportunities, commissioners can better understand the diverse health requirements of different groups and target interventions accordingly. Data and analytics are central to this transformation, enabling the identification of trends, risks and areas for early intervention before pressures escalate.

Strategy development should be rooted in population insight, ensuring priorities are set based on the potential for the greatest impact. Healthcare utilisation management provides intelligence to inform resource allocation decisions that align capacity with actual needs. This approach ensures resources are deployed where they are most effective, reducing inefficiencies and addressing inequities across the system. Digital transformation will be critical in delivering this vision, empowering commissioners to work at system-wide levels and make data-driven decisions that optimise outcomes and ensure the NHS remains sustainable in the face of growing demand. To do so, system partners need to be able share data and access to patient records across different platforms.

Case study: North Central London's data-driven approach

North Central London ICB shows how sophisticated data analysis can transform commissioning decisions. The ICBs’s work on specialised services demonstrates the power of linking data across pathways. The system has brought together clinicians from across different settings to interpret complex data and propose new ways to address population needs. For example, their work on liver disease pathway redesign shows how data-driven insights can shape more preventative approaches to care, bringing together public health, population health staff, and clinicians from primary and secondary care.

Case study: Population cohort segmentation in Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester (GM) ICS provides healthcare for 3 million people living in ten places. As a system, GM has sought to improve population health while at the same time improving the financial position and service performance. To understand the health needs of the population, the ICS has used linked patient-level data and segmented the GM population to inform service and financial planning. Learning from Greater Manchester’s approach has been shared through via the NHS Confederation’s member forums and replicated by other ICSs.

2. From downstream to upstream

The future of NHS commissioning must prioritise a shift from downstream care, where ill health is treated as or when complications develop, and towards upstream, preventive measures that address the root causes of ill health. Prevention must take centre stage in commissioning decisions, ensuring that services are designed and funded to reduce the incidence of illness before it arises.

By supporting self-care and healthy lifestyle behaviours (primary prevention), the NHS can empower individuals to take greater control of their health, helping to reduce future demand on services. Early intervention also plays a crucial role in changing life trajectories, particularly by addressing risks and inequalities that, if left unaddressed, lead to more complex and costly care. Achieving this vision requires overcoming the significant barriers to prevention outlined in the NHS Confederation’s report, Unlocking Prevention in Integrated Care Systems, which explores the challenges and opportunities in embedding prevention within system-wide plans.

This upstream approach is underpinned by population health management, which uses data to identify trends and shape services around the needs of communities. Commissioners must increasingly look beyond traditional healthcare providers, recognising the value of community assets such as voluntary organisations, social networks, and local infrastructure, as part of the solution to improving health and wellbeing.

Primary and community care interventions, which prevent admissions to secondary care (secondary prevention), are also crucial. ICSs that invest more in community care have 15 per cent lower non-elective admission rates and 10 per cent lower ambulance conveyance rates. Every £1 spent on public health, primary and community care is correlated with £14 in gross value added to the economy.

To sustain this shift, investment should follow prevention opportunities, focusing resources on interventions with the potential to deliver long-term health benefits and alleviate pressure on the wider health and care system. Current approaches to measuring productivity are mostly limited to the acute sector and are activity based. Finding new ways to measure the benefits of shifting care and reducing more expensive activity will be crucial. A move from annual to multi-year planning cycles and allocations will help, as not all the benefits of prevention will be realisable over an annual cycle. Currently, high-value investments are sometimes deprioritised if they do not deliver a return in-year, ultimately perpetuating the financial challenges faced by ICSs.

3. From competition to collaboration

Sustainable system change depends fundamentally on strong relationships and shared objectives between partners. Technical solutions and structural changes alone cannot deliver transformation without the foundation of trust between organisations and professionals. In future, commissioning should facilitate a transition from competition between organisations to better collaboration across the health and care system. Although this will take time, joint mechanisms must replace organisational silos, enabling integrated working and fostering a culture of shared responsibility for outcomes.

Shared financial arrangements are critical to this shift, providing the foundation for collective action by aligning incentives and encouraging organisations to pool resources for the greater good. For example, a greater emphasis on a zero-based approach to spending or ‘open-book accounting’ could be explored. Performance standards must also evolve to operate seamlessly across boundaries, ensuring accountability and driving improvement in integrated service delivery across the system, not almost exclusively on acute sector activity.

This collaborative approach extends beyond the NHS, with social care and the third sector becoming equal partners in planning and delivering services. Initiatives such as the Better Care Fund should be geared toward realising the paybacks from pooled resources, allowing investment in services that reduce duplication and improve outcomes. Place-based partnerships are essential to driving integration at the local level, with Section 75 arrangements offering the legal and operational flexibility to support joint initiatives. The Provider Selection Regime (PSR) can enable a more co-ordinated and planned approach to procuring services. Together, these mechanisms create a framework for collaboration that moves away from transactional relationships, ensuring that the needs of patients and communities are placed at the heart of commissioning decisions.

Case study: Collaborative commissioning in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland

Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland's integrated commissioning demonstrates how collaborative commissioning can work in practice. By implementing sophisticated pooled budget arrangements and joint commissioning approaches, they have moved beyond traditional organisational boundaries. The approach brings together health and social care resources through innovative risk-sharing agreements, enabling more flexible and responsive service delivery. This collaboration has proven particularly effective in areas like intermediate care and support for people with complex needs.

4. From transactional to transformational

A shift from a transactional to transformational approach is required to achieve sustainable improvements in health outcomes and system efficiency. Pathway commissioning, which focuses on the patient’s journey through services, must replace traditional organisation-based deals, to ensure care is designed and delivered holistically rather than fragmented by bureaucratic boundaries. Innovation will then drive decision-making across the system, embedding it as core business rather than allowing it to be treated as an optional add-on.

Transformational commissioning requires shared infrastructure to enable system-wide change and quality improvement initiatives that span organisational boundaries, fostering collaboration and integration. A stewardship model should empower staff and patients, giving them greater understanding of and influence in the way services are shaped and aligning care with the needs of the population. Additionally, long-term planning must take precedence over short-term, annual contracting cycles, to ensure that investments are aligned with strategic goals and that improvements are sustained over time. A forward-looking approach of this kind is essential to build a resilient health and care system capable of meeting the complex challenges that lie ahead.

Case study: HomeFirst in Leeds

The Leeds Health and Care Partnership’s HomeFirst Programme demonstrates how transformational partnership working can deliver tangible results. The partnership’s multi-agency HomeFirst Programme, developed through partnership between the council, integrated care board, NHS trusts, primary care and the voluntary and independent sector, has fundamentally redesigned intermediate care services. Rather than simply contracting for existing services, the system created a new person-centred, home-first model that spans organisational boundaries. The results speak to the power of this approach: 1,212 fewer adults a year admitted to hospital; a 36 per cent reduction in length of stay for people who no longer need to be in hospital requiring support on discharge; a 9.9-day reduction in short-term bed stays; and 607 more people returning home each year rather than being admitted to long-term care, compared to the baseline period.

5. From cost to value

The future of commissioning requires a more holistic approach to resource allocation, moving beyond traditional budgeting methods to ensure that funding is aligned with population needs and long-term health outcomes. Programme budgeting could help reflect the specific requirements of different population groups, enabling commissioners to direct resources where they are most needed. Pathway funding should replace siloed payment models, supporting integrated care and incentivising the transformation of services across entire patient journeys. Alongside these shifts, the adoption of new incentives such as blended or outcomes-based payments, will be critical in driving the delivery of more efficient and effective care.

Long-term and aligned financial planning between the NHS and local government is essential to create the space for transformative change, allowing organisations to invest in innovations that deliver paybacks over time. This philosophy must be underpinned by new productivity metrics that go beyond traditional efficiency measures, capturing the true value of care delivered across the system. Tools like an integration index, proposed in the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan but not yet operational, can measure what matters most, such as patient’s view of the care experience as well as outcomes and equity.

Commissioning decisions, including on medicines, should be factored in the downstream benefits of early intervention and prevention. The Provider Selection Regime also allows commissioners to make procurement decisions based on the overall return on their investment of public money, not just the lowest price. Together, these changes will support commissioners to make smarter, data-driven decisions that balance immediate pressures with long-term system sustainability.

Medicines are the most common healthcare intervention and second largest (and growing) area of NHS spend after staff. Optimising use of medicines is therefore essential to improving health outcomes, patient safety and value for money. In an ICS landscape, that medicines optimisation function needs 'systemisation', so it is better able to integrate activities across different providers and achieve better value for money, not just try to control costs. More progress is also needed to understand and manage the homecare medicines market, which could be an important driver of the shift from hospital to community care.

6. From compliance to leadership

Systems must evolve to empower leadership at all levels to drive sustainable improvement. Too often, overbearing instructions from the centre and risk aversion at a local level drives a culture within the NHS of compliance and looking upward for direction. Instead, policy should encourage and reward entrepreneurial leadership that looks outward for solutions, with greater risk appetite for doing things differently. Given the growing pressure on services, the overall risk of standing still outweighs the risk of change. However, the top-down compliance culture can mean that balance of risk for individual leaders can be the opposite.

Clinical leaders should play a central role in shaping system direction, using their expertise to guide strategic decisions and align services with patient needs. Frontline staff, empowered to influence priorities, will become instrumental in identifying issues early, proposing solutions, and ensuring care is grounded in real-world practice. Equally important is the participation of residents in service design, ensuring that those who rely on the NHS have a meaningful voice in shaping the future of healthcare delivery. ICBs’ chief medical officers and chief nursing officers embed clinical leadership on ICB boards, but clinical expertise in the provider sector should also be utilised to inform planning, particularly for provision of specialised services.

This distributed model of leadership encourages a greater appetite for risk and experimentation, underpinned by a cultural transformation that fosters innovation and continuous learning. Place-based leadership can then develop rapidly, enabling communities to respond flexibly to local challenges, while provider collaboratives will take on new roles that transcend traditional organisational boundaries. By dismantling existing hierarchies and nurturing a culture of shared responsibility, the NHS will move beyond compliance and embrace a leadership ethos capable of delivering better outcomes for all. Guidance and policy should focus on ‘what’ and ‘why’, leading ‘how’ to local determination.

Case study: Mid and South Essex's Stewardship Programme

Mid and South Essex exemplifies this shift toward distributed leadership through its innovative stewardship programme. Rather than maintaining traditional hierarchical controls, the system has developed a model where leadership responsibility is shared across multiple levels and organisations. The programme focuses on building capabilities among clinicians and managers to act as system stewards rather than just organisational leaders. This approach has enabled more rapid service transformation by empowering local decision-making while maintaining collective accountability for outcomes.

How we get there: enablers for strategic commissioning

To bring about lasting reform, ICBs will need to convene system partners to, over time, make a decisive shift from contracting individual providers for activity (or services), towards contracting that drives collaboration to improve people’s health (or outcomes). For this work, we define strategic commissioning as:

‘The pursuit of the best possible health outcomes for a given population and experience for patients through the planning, purchasing, evaluation, integration and transformation of services, promotion of self-care and exercising system leadership to that end.’

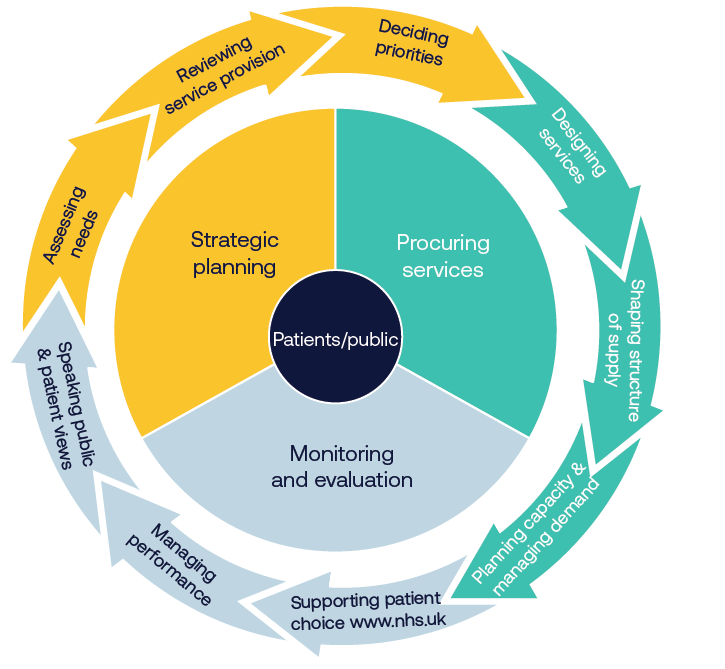

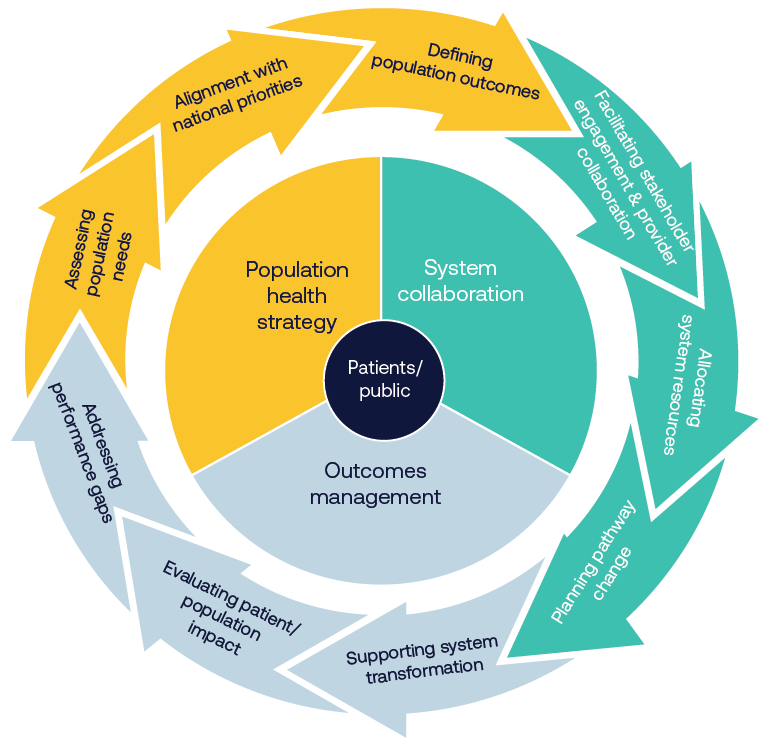

At present, different stages of the NHS commissioning cycle can be illustrated as follows:

Before

After

Joint forward-planning processes

Effective strategic commissioning requires robust population health planning. ICBs already undertake comprehensive population health needs assessments, using population health management systems and drawing on a rich array of data sources including public health data, hospital episode statistics, primary care data and social care metrics. Integrated care strategies are drawn from joint strategic needs assessments led by health and wellbeing boards. Quantitative analysis should be enriched by extensive community and stakeholder involvement to understand real local priorities, with particular attention paid to health inequalities and underserved populations.

These assessments will inform the development of specific, measurable population health outcomes across patient cohorts. Such outcomes span multiple domains: clinical metrics relating to disease progression such as diabetic complications; quality of life measures including improved mobility for elderly populations; system effects like reduced emergency admissions; and health equity metrics such as reduced variation in screening uptake. Each desired outcome will need to be accompanied by clear baseline metrics and should pinpoint the process improvements required, to provide a calibrated framework to measure progress and success.

If the ICP’s integrated care strategy sets the high-level outcomes system partners want to achieve, the ICB’s joint forward plan should set out how the ICB will allocate resources to achieve the NHS’s contribution to the integrated care strategy. Together, these strategies will form the basis for determining how and when resources need to be redeployed. Annual system plans constructed around the objectives declared will provide the concrete framework against which the contribution of all providers will be judged and rewarded. The timely publication of NHS England’s annual planning guidance and a streamlined approach to setting targets, such as the case for 2025/26, can support this planning process.

An enhanced incentive structure: payment mechanisms and tariffs

At present, commissioning processes are not geared towards influencing ways of working in operational delivery. Once funds have been committed to the detailed parameters set out in a provider’s contract, commissioners’ levers for change in real time tend to disappear. The actual deployment of resource becomes a matter for operational management. The dichotomy and binary nature of NHS contracting arrangements helped preserve stability when nascent systems were being established and while the driver of change was to incrementally improve standards of delivery and expand provision. But delivering the shifts outlined previously means rethinking our financial framework.

Currently, financial flows within the NHS are fragmented and work against integration. The different parts of the NHS – primary care, community care and hospital care – are not financially incentivised to work better together. The financial system does not allow all partners to benefit from returns on investments in another part of the system, disincentivising some quality-improving and cost-saving investments.

Payment by activity for acute elective care and block contracts elsewhere incentivises continuing flow of a greater share of NHS spending to later stage downstream interventions, rather than upstream where strategic commissioners want to shift resources. Paying for downstream activity based on demand and cost does little to improve value nor prevent that demand through earlier, cheaper intervention.

Different models should be explored that offer suitable and aligned incentive structures combining both financial and non-financial elements to encourage strong engagement and real commitment to improved outcomes. One option is to link baseline allocations to the portion of current budgets used to support provision formally designated as ‘essential services’. This could free up part of existing allocations so that they could help to offer additional outcome-based payments tied to the achievement of agreed population health goals. Monies not ‘earned’ under such arrangements would not be lost to the system, since shortfalls in one budget would be matched by uncommitted resources retained in another, but in the longer term funds would not continue to be distributed in such a way as to perpetuate failure or persistent shortfalls.

Contracting for specific health outcomes across a whole pathway for a specific patient cohort can help incentivise earlier and more cost-effective interventions, boosting allocative efficiency. However, this requires an appropriate ‘gain-share’ mechanism - or ‘loss-share’ mechanism if outcomes are not achieved – to ensure all system partners see a financial benefit and unite behind shared goals. Further information on existing models of outcomes-based commissioning and available options can be found in the NHS Confederation’s report, Unlocking Reform and Financial Sustainability: NHS Payment Mechanisms for the Integrated Care Age.

A shared savings model could similarly be used to reward achievement of population health outcomes that offered quantified ‘paybacks’. And specific incentives for reducing health inequalities might be a way of driving desired change, in the same way that service development funding monies have hitherto been used to secure particular service effects nationally. Locally, pooled budgets for shared priorities or matched funding arrangements for collaborative initiatives would be a natural extension of existing joint investment schemes.

Case study: Bundled payment system in the Netherlands

The Netherlands' bundled payment system for chronic conditions demonstrates how financial mechanisms can drive integration. The approach of single payments for complete care pathways led to improved diabetes care outcomes while reducing system fragmentation.

Alongside contracts, prices are also important. Current tariffs presume that the cost base of existing providers should provide a starting point for all decision-making. This approach perpetuates historical patterns of resource deployment and may no longer serve current needs. Once resources are committed to organisational budgets, their use can alter dramatically in-year. Length of stay can deteriorate, workforce changes may damage productivity, and overheads can increase without external scrutiny.

Two specific examples illustrate the challenges of current arrangements. Individual funding requests (IFRs) continue to consume commissioner time and resources despite the requisite clinical expertise – and all the commissioned resource - residing in providers. Similarly, out-of-area referrals often encourage providers to pass responsibility on to third parties rather than developing local solutions. These mechanisms need fundamental reform to support genuine system transformation.

System collaboration

To date, provider collaboratives have tended to operate within single sectors. For example, mental health provider collaboratives managing specialised commissioning budgets or acute provider collaboratives sharing clinical support services. These arrangements have demonstrated significant success in areas such as reducing out-of-area placements in mental health, standardising clinical practices, sharing workforce and delivering efficiencies through shared services.

Case study: East Midlands (IMPACT) Provider Collaborative

The East Midlands (IMPACT) Provider Collaborative for low and medium adult secure mental health services, led by Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, consists of nine NHS and independent sector organisations. The IMPACT Provider Collaborative has a clinical model that seeks to transform adult secure care services across the East Midlands through improving patient pathways, the interfaces between the health, social care and criminal justice system, and ongoing service development. The collaborative has been able to reduce out-of-area placements from 20 per cent of patients to 5 per cent in 2023/2024.

However, strategic reform necessarily entails a significant evolution of how providers work together, extending collaboration beyond single sectors to encompass whole pathways of care. Achieving population health outcomes requires integration across the entire care journey, from primary care and community services through to acute care, mental health, social care, specialised services and the VCSE sector. This represents a step change in collaboration, to ensure shared accountability for the health outcomes defined in joint forward plans and integrated care strategies.

The successful elements of existing collaboratives - shared governance structures, risk-sharing arrangements, and operational protocols – can act as a springboard for extending them across traditional sectoral boundaries. For example, where mental health collaboratives have successfully reduced out-of-area placements through better coordination between mental health providers, this approach could expand to include primary care management of mental health, community-based crisis prevention, acute hospital liaison and social care support. Genuine end-to-end pathway integration would be supported by corresponding organisational and contractual mechanisms, with all providers sharing responsibility for specific results geared to producing desired population outcomes.

In this new model, providers collectively would have to align their resources to population health goals, rather than focusing separately on incremental improvements to services defined by their siloed funding envelopes. Clinicians and managers across the whole system would together take responsibility for pursuing broader outcomes. For instance, in managing population health for people with diabetes, primary care, community services, acute hospitals and mental health services would need to work in close partnership, sharing responsibility for everything from prevention and early intervention through to complex care management.

This evolutionary approach builds new elements into existing collaborative mechanisms by:

- extending successful governance models to encompass multi-sector partnerships

- creating shared accountability frameworks that span entire pathways

- developing integrated workforce models that enable staff to work flexibly across sector boundaries

- establishing shared clinical protocols that ensure consistent care delivery regardless of setting

- incentivising data and digital infrastructure that enables genuine population health management across all care settings.

The end goal is to create a model of system collaboration that matches the scope of the outcomes providers would together be responsible for achieving. One that moves from impressive but sector-specific improvements to genuine patient-focused transformation that can deliver the population health ambitions that ICBs are supposed to pioneer, and with a genuinely system-focused approach to performance management and oversight.

Oversight, accountability and performance management

Nationally, new mechanisms will be required to ensure mutual accountability for outcomes that will require the input and involvement of multiple organisations. As NHS England functions are brought back into the DHSC, further work is needed to ensure a clear delineation of functions between ICBs and the DHSC, including any new regional approach. This should build on the engagement and insights from the development of NHS England’s improvement and assurance framework4.

NHS England previously signalled a change in its operating model that will see ICBs leading strategic commissioning and population health planning, while NHS England will assume responsibility for direct performance management of providers. ICBs will continue to have oversight of how providers deliver the outcomes that they have been commissioned to achieve for their population and need to build the requisite skills to do this. This ICB oversight role is essential to empower them to be pioneers of reform and to drive delivery of the three shifts. Providers’ statutory responsibilities for delivery, quality, safety and collaboration will be aligned in real time as never before. But for ICBs to oversee providers’ delivery of outcomes, they will also need to maintain the skills and expertise to oversee the quality and safety of services within the context of constrained management spend.

Performance monitoring is increasingly supported by real-time dashboards of key indicators, regular collaborative performance reviews and comprehensive tracking of patient experience and outcomes. Learning networks across provider collaboratives and systems can be used to facilitate continuous improvement, supported by best practice sharing forums and joint training programmes 4 .

This includes the National Oversight and Assessment Framework (including ICB Capabilities Guidance, Performance, Improvement and Regulation Framework), and forthcoming updated NHS England Operating Framework and Strategic Commissioning Framework.

Risk management and success metrics

Effective risk management is integral to the success of this new way of working. Key risks around provider engagement, data quality, financial sustainability, workforce capacity and clinical safety will be actively managed as part of NHS England’s performance management regime. This will be done through early stakeholder engagement, development of shared processes, phased implementation approaches, joint workforce planning, and robust governance. The ICB’s role as a convenor that can take a system view will be particularly important.

Success can be measured both at system and operational levels. System-level metrics will track improvements in population health outcomes, reduction in health inequalities, value for money and patient experience. Operational metrics will focus on provider collaboration, quality standards, workforce satisfaction, service integration and financial performance. As much as possible, these should be streamlined and specific to support transformation and delivery to ensure leaders and staff have the headspace and time to deliver the changes needed.

Chapter footnotes

- 4. This includes the National Oversight and Assessment Framework (including ICB Capabilities Guidance, Performance, Improvement and Regulation Framework), and forthcoming updated NHS England Operating Framework and Strategic Commissioning Framework. ↑

How we get there: supporting individual and organisational development

Individual skills and capabilities

Systems need both responsibility and capability to drive reform. The evolving healthcare landscape demands leaders capable of making and implementing challenging decisions while wielding sophisticated analytical capabilities to drive evidence-based change. These individuals must develop advanced skills in data analysis and interpretation, alongside the diplomatic abilities needed to build and maintain effective partnerships across complex systems.

Data analysis is essential to realising a proactive care model and driving productivity. However, ICBs have argued that they need enhanced capability and capacity to do this as effectively as possible. For example, this has come up following delegation of pharmacy, optometry and dentistry commissioning and specialised commissioning. Efforts to invest in and improve capability and capacity have been hindered in many areas by the 30 per cent reduction to ICBs’ running cost allowance.

Diplomatic skills will also be essential to realise more collaborative working and allocative efficiency. Strategic commissioners will need to be more relational, strategic and collaborative in the way they work with providers, the VCSE sector and local authority partners. This 'one team' approach needs to be evident at all levels, creating a unified culture that supports genuine integration and collaborative working. Strategic commissioners will need to be expert facilitators to bring community insights into the design of new models of proactive care to achieve the outcomes through early intervention and prevention. Developing strong persuasive skills will be key to this.

System leadership, built on an understanding of complex adaptive systems, is crucial to building cohesive teams that transcend traditional organisational boundaries. Individuals should be supported to become effective system leaders and given the time and space to build relationships effectively. This requires combining strategic thinking with entrepreneurial action, fostering innovation while maintaining a holistic view of system needs and opportunities. Future leaders will need to prioritise system benefit over individual organisational gain, consistently asking how they can support their system partners. This may involve holding contradiction and uncertainty. The NHS Confederation offers specialist programmes and consultancy services to advance leadership capability and embed improvement approaches across health and care.

Contract management expertise should evolve to encompass both traditional transactional approaches and new models of transformational pathway commissioning. These technical skills need to be underpinned by a deep understanding of how to commission across entire pathways rather than individual services.

Estate management capabilities will become increasingly crucial for system transformation, moving to new estate models and unlocking value from existing underutilised assets to reinvest in future needs, as identified in the Naylor review. The NHS Confederation has already proposed devolving expertise, resource and assets from NHS Property Services into systems to do this, with any remaining functions that need national scale absorbed into NHS England.

Organisational development

Organisations must develop robust change management capabilities to maintain stability during transformation, while evolving their operating models to support new ways of working. This includes building mechanisms for cultural development and establishing effective peer review processes that support continuous improvement and learning across the system.

The focus needs to be on developing new approaches to working across traditional boundaries, creating structures and processes that enable genuine collaboration between different parts of the system. This requires organisations to fundamentally rethink how they operate, moving from siloed approaches to truly integrated ways of working.

National and regional bodies as well as organisations at system, place and neighbourhood levels will need to consider how they must shift their ways of working to make strategic commissioning a reality. To support system-level organisational development, the NHS Confederation proposes a strategic commissioning forum to help leaders learn from each other and drive forward organisational development at pace.

Case study: Working across organisational boundaries towards common goals in Sweden

Sweden's Jönköping Region built its internationally recognised healthcare improvement programme on a foundation of trust and shared purpose across organisational boundaries. Their ‘Esther’ model, focusing all partners on common patient-centred goals, has delivered sustained improvements in care quality and efficiency.

Case study: Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes’ Primary Care Workforce Programme

The BLMK Primary Care Workforce Programme is a large-scale holistic programme that supports its primary care providers through a large-scale holistic programme, including:

- developing learning organisations where staff are supported and empowered to learn and train together and development is prioritised

- culture and organisational development, where workplaces embed the ingredients to attract, retain and nurture staff

- leadership development where staff develop the adaptive system leadership competencies and behaviours to support system-wide transformation

- integrated neighbourhood working, empowering our workforce to connect and build relationships across organisational or professional boundaries within their neighbourhood.

Nationally – direction, stability and knowledge sharing

At the national level, leadership will increasingly involve clear objectives and identifying opportunities for standardisation and efficiency through 'do it once' approaches. These objectives should be consistently framed in terms of population health outcomes rather than traditional activity metrics, creating a clear line of sight between national priorities and local delivery. The national tier has a crucial role in delivering priority projects at scale, leveraging its unique position to achieve NHS-wide value. This includes using national purchasing power and establishing frameworks that enable local systems to focus on implementation rather than reinventing common solutions.

Elsewhere, the national level should seek to support systems in areas where they ask for help (a service model) and continue to devolve functions, responsibilities and capacity for functions that can better be delivered at a more local level, closer to populations. Resources should be aligned with ambition, supported by integrated regulatory functions that enable rather than inhibit change. This requires a careful balance between maintaining national standards and allowing local systems the freedom to develop approaches that work for their populations and circumstances.

National policy must provide the structural stability necessary for local reform to flourish, maintaining consistency in policy approach while reforming oversight mechanisms to support system working and empowering ICBs to drive change. This stability needs to be balanced with sufficient flexibility to allow local systems to innovate and adapt to their specific circumstances.

At system level

Systems are responsible for setting comprehensive strategies that encompass all aspects of health and care delivery within their geography, working collaboratively to agree local priorities that reflect both national requirements and local needs. This strategic role requires building strong relationships across all system partners.

The focus at system level should be on developing effective system leadership and fostering a 'one team' approach that brings together all partners in pursuit of shared goals. This includes creating structures and processes that enable genuine collaboration and shared decision-making.

ICSs should increasingly use peer review to laterally drive change and be supported and encouraged to do so by national policymakers. Peer review has long been an effective driver of improvement in local government.

At place and neighbourhood

At place level, the focus is on tactical implementation of system strategies, turning high-level plans into practical actions that deliver real change for local populations. This includes commissioning at place, enabling effective collaboration between local partners and supporting the development of primary care networks and collaboratives.

Place-based leadership has a crucial role in driving neighbourhood integration, ensuring that services work together effectively at the most local level. This includes supporting the development of integrated care models that respond to local needs and preferences while maintaining alignment with system priorities. Neighbourhood healthcare should:

- provide wraparound care for those who need it more

- promote health and wellbeing and improve the relationship with communities

- increase community resilience.

The ten-year health plan will need to clarify the vision for neighbourhood health to inform local implementation.

Making change happen: three stages of changes

Sir Michael Barber suggests three stages to changing behaviour to deliver public service reform, supported by development at three levels that may guide the development of strategic commissioning in practice.

Stage 1: Awareness raising

Develop a comprehensive understanding of strategic commissioning's role in system transformation, while building a shared vision of the desired future state. Through collaborative engagement, systems work to define a clear and compelling case for prioritised changes, creating the necessary momentum for transformation across all partner organisations and stakeholders.

Stage 2: Formal training

Build the essential capabilities required for effective strategic commissioning, encompassing the development of sophisticated data and analytical skills alongside strengthened relational leadership capabilities. This includes enhancing expertise in contract and pathway management, while supporting the development of new competencies that enable staff to work effectively in more strategic and collaborative ways across traditional organisational boundaries.

Stage 3: Embedding through learning and culture

Establish sustainable mechanisms for continuous improvement through the creation of peer review processes between systems and active learning networks. By sharing successful approaches and embedding an improvement culture, systems can sustain positive changes through collaborative working. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle of learning and development that supports ongoing system evolution and improvement.

Implementing strategic commissioning

The transition to strategic commissioning will require careful implementation through sequencing and sustained focus and relies on building the right skills as described above. The following recommendations span four phases, from establishing core infrastructure to embedding cultural change. While some elements can proceed in parallel, success depends on building foundations systematically and monitoring progress throughout.

Setting out the vision and establishing support infrastructure (0-6 months)

The publication of a ten-year health plan in late spring 2025 will set out a roadmap for change and articulate a clearer vision for neighbourhood health. NHS England should establish the structures needed to support transformation across all levels. NHS England’s forthcoming strategic commissioning framework should reflect the principles and proposals outlined above and be accompanied by an implementation plan to drive change. Alongside this to support delivery, a national commissioning forum should be created to enable structured peer learning and provide rapid feedback on policy implementation. Place-based partnerships need particular support to develop effective governance and delivery mechanisms.

Reforming planning and performance systems (6-12 months)

The annual planning process requires fundamental revision to support the new approach to strategic commissioning. This includes updating all planning templates to incorporate pathway-based commissioning and collaborative delivery models. The existing ICB scorecard must evolve to measure what matters for population health improvement, moving beyond traditional activity metrics to capture system integration and outcomes.

Systems should be supported to increase the utilisation of existing data and share learning platforms where evidence, good practice and standardised resources for partnerships agreements can be accessed. These practical tools and frameworks will enable systems to implement new approaches while maintaining consistency where appropriate.

NHS England should develop a comprehensive data skills programme, supported by regional implementation networks. This must go beyond basic analytics to include advanced population health management techniques, predictive modelling, and outcome measurement. Standardised tools for population health needs assessment should be developed centrally to avoid duplication of effort across systems.

Implementing new ways of working (12-24 months)

Systems should begin implementing pathway-based commissioning models, starting with services being delegated from NHS England. This provides an opportunity to test and refine new approaches while maintaining service stability. New financial frameworks that enable risk-sharing across systems must be developed and implemented, supported by system-wide outcome measures linked to population health goals.

Integrated data systems enabling real-time performance monitoring should be supported, alongside capability assessment frameworks that track progress in strategic commissioning. These technical developments must be accompanied by cultural change programmes that support new ways of working.

Embedding cultural change (Ongoing)

Sustaining transformation requires embedding new behaviours and ways of working across the system. Learning networks should be established across ICBs, focused specifically on strategic commissioning challenges and solutions. Formal mechanisms for sharing successful approaches between systems should be created, supported by metrics that track cultural change and collaborative working.

Regular peer review processes between systems should be implemented, using evaluation frameworks that capture both quantitative and qualitative progress. This will create a self-reinforcing cycle of improvement and learning across the NHS.

Monitoring progress

Progress monitoring must focus on tracking implementation across all these areas, using a balanced set of metrics that capture both technical and cultural change. Key areas for measurement include:

- implementation of new commissioning approaches

- development of system capabilities

- cultural change and collaborative working

- population health outcomes

- financial sustainability

- service integration

- patient experience and outcomes

Regular assessment against these metrics will enable early identification of challenges and sharing of successful approaches across systems.

The successful implementation of these recommendations will require sustained commitment from all system partners. However, the potential benefits in terms of improved outcomes, better value for money, and more sustainable services, make this investment essential for the NHS's future.

Conclusion

The way the NHS plans and manages the use of public money – commissioning – needs to adapt to meet the health challenges of today. A more proactive model of care, which puts more effort in keeping people well and preventing worsening ill health, will require a substantial shift in resources away from hospitals towards the community and prevention. Strategic commissioners’ role is to do this.

While the structures introduced by the Health and Care Act 2022 are the right ones, delivering change requires more than an act of parliament. This report has set out six shifts in the approach to commissioning, both by ICBs and lead providers:

- From reactive to proactive.

- From downstream to upstream.

- From competition to collaboration.

- From transactional to transformational.

- From cost to value.

- From compliance to leadership.

Commissioning will become more strategic when it moves from transactional relationships with individual providers of episodes of care to commissioning whole pathways of care, requiring providers to collaborate towards the shared goal of improved health. Given the increased population scale and new or forthcoming delegated commissioning responsibilities that unite budgets for whole pathways of care, ICBs are uniquely placed to do this.

Delivering strategic commissioning will require some practical steps. The DHSC, working with NHS England through its transition period, needs to support the further development of system-level workforce skills, data analysis, diplomatic skills, system leadership, contract management expertise and estate management capability through training and ICB recruitment. ICBs can then harness these competencies to take a population cohort segmenting approach, designing services and pathways with partners around the needs of these patient cohorts, including earlier intervention. The 50 per cent reduction in running cost allowance for ICBs will need to be managed carefully or it risks bringing to a standstill any efforts by ICBs and their partners to deliver on strategic commissioning and the government’s plans for NHS reform.

To support this service transformation and reallocation of resource, ICBs could use outcomes-based contracting for these populations across pathways. Vertical provider models and collaboratives should take on more responsibility and accountability for patient outcomes, to help integrate service delivery and align incentives in often fragmented provider landscape.

Finally, NHS the future oversight regime needs to support and incentivise this change, better balancing management of performance today with oversight of the delivery of this reform for tomorrow. Within systems, ICBs must maintain oversight of providers’ delivery of outcomes - an essential lever to drive the government’s reform agenda. Alongside this, a smaller number of national priorities and targets that focused on ends not means could liberate local leaders to lead, innovate and drive change tailored to the needs of their populations. Aligning these steps to mobilise change and achieve more than the sum of their parts puts the ‘strategic’ into ‘strategic commissioning’.

This vision of change is based on engagement with and the views of local system leaders. We hope it may make a constructive contribution to NHS England’s upcoming strategic commissioning framework and how to mobilise change through the ten-year health plan.