Key points

Following the Hewitt review recommendation to consider alternative payment mechanisms within the health system, this discussion paper explores examples of international and domestic payment mechanisms. The paper is intended to support further discussion and debate and to inform future policymaking to support integration.

Currently, financial flows within the NHS are fragmented and work against integration. The different parts of the NHS – primary care, community care and hospital care – are not financially incentivised to work better together. The financial system does not allow all partners within an integrated care system (ICS) to benefit from returns from investments in another part of the system, disincentivising some quality-improving and cost-saving investments.

Payment mechanisms, although not a silver bullet, can be a crucial factor in enabling changes in services and behaviour which can boost allocative and technical productivity, including a leftward shift to earlier, more preventative, upstream interventions. This is crucial to improving health outcomes and the financial sustainability of the health and care system given rising demand for services driven by demographic trends.

This discussion paper is intended to contribute to policy debate, rather than propose ideal type solutions, and reflect honestly on the advantages and the disadvantages of a range of available payment mechanisms and the different behaviours they can incentivise.

It also identifies wider factors which need to be aligned to enable payment mechanisms to provide effective incentives. Effective data analysis, longer-term financial planning and capital investment feature among the crucial factors that need to align with payment mechanisms to boost NHS productivity.

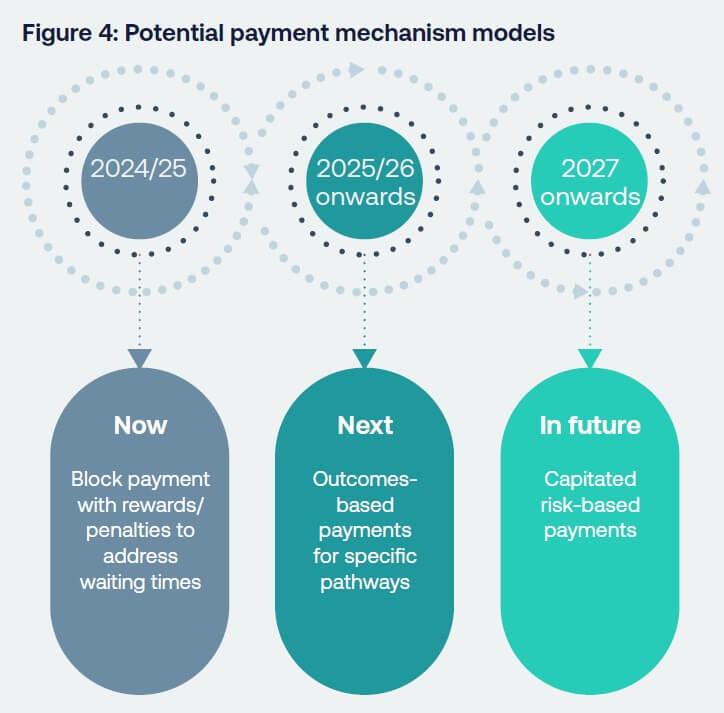

The paper suggests three options for consideration over the short, medium and longer term. None should be compulsory and we encourage experimentation, learning and tailoring the choice of intra-ICS payment mechanisms to the particular needs of each ICS.

1) Now – Further use of flexibility within the existing NHS Payment Scheme to experiment locally, including considering options such as West Yorkshire’s block payments, with a rewards and penalties model to incentivise cutting waiting times for elective care

2) Next – Development of pathway-based payments by outcomes, starting with pathways for care of the frail and elderly to incentivise admissions avoidance.

3) In future – Adoption of risk-weighted, capitated payments for NHS services in England, learning from international best practice including OptiMedis in Germany and ChenMed in the USA.

This discussion paper has been developed by a small working group; members of the group have participated in an individual capacity. This publication does not necessarily represent the views of all members of the group, their organisations nor all members of the ICS Network or the NHS Confederation more widely. We recognise that suggestions within the paper will generate debate within our membership and look forward to continuing the discussion. The paper has been developed in collaboration with KPMG.

Introduction: the drive for reform

The challenge of boosting productivity to meet growing demand

The NHS today faces considerable challenges. Improvements in life expectancy have stalled since 2010 and health inequalities have widened, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. [1] Around 7.75 million people are on the waiting list for planned treatment and waiting times continue to grow. [2] People are struggling to access primary care and waiting times for mental healthcare are similarly concerning. Staff are demoralised, as demonstrated by repeated industrial action and a fall in satisfaction in the latest NHS Staff Survey. [3]

The context for these challenges is not unique to the UK. Demand for healthcare services is continually rising disproportionate to the rest of the economy, primarily driven by an ageing population, as well as changing lifestyles, rising multi-morbidities and ever-evolving technologies enabling us to deliver more and more. [4] Today, nearly half of the UK population suffers from a long-term health condition, which will continue to consume a high proportion of healthcare expenditure. [5] Mental health conditions for children and young people are also rising. [6] The model of care envisaged when the NHS was founded in 1948 – of patients coming into hospital, receiving treatment, then going home healthy – is no longer the norm. At the same time, the scope of healthcare is continually expanding – from high-tech care for people with cancer to increasing medicalisation of common situations – and as such, so do public expectations of what the NHS should deliver.

As a result, demand for care is rising. For example, between 2010/11 and 2019/20, the number of hospital admissions rose approximately 16 per cent. [7] Overall GP consultations per registered patient per year for clinical staff groups rose from 4.29 in 2010/11 to 4.91 in 2014/15 and 5.66 in 2021/22. [8,9] By 2040, the number of people projected to be living with major illness in England is expected to rise to 9.1 million (2.5 million more than in 2019). [10] In an attempt to keep up with this, more and more money has been spent on healthcare – NHS expenditure has grown from £131.8 billion to £161.1 billion in 2010 to 2023/24 (equivalent to rising from 8 per cent to approximately 11 per cent of GDP). i

This growth in spend has corresponded with growth in the NHS workforce – between 2010 and 2023 staffing has increased by 315,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff (a 21 per cent increase). Much of this growth has been more recent, with an increase of 216,000 staff since 2019, (15 per cent). ii The rate of NHS productivity growth has averaged 0.9 per cent over the past 25 years, insufficient to keep pace. We should still note that healthcare productivity growth is higher than any other UK public sector services over the same time period. [11]

After rising for the previous two decades, overall productivity began falling by the end of the 2010s and has worsened following the COVID-19 pandemic. [12] Recent increases in staffing have often not translated into increases in volume of activity for many types of care. [13] However the extent of this is not fully clear as current measures of productivity capture volume rather than value of care, so falls in productivity growth are not as large as the data may suggest. Recent high inflation, particularly in energy and medicines prices, have contributed to a lower productivity figure. Nevertheless, significantly increasing productivity is therefore one of the greatest challenges facing the NHS. Improving healthcare productivity has a key role to play in lifting the UK’s overall productivity malaise.

Freedman and Wolf attribute lower productivity to: (a) the lack of capital investment for estate and digital infrastructure, which has made it harder to treat patients and caused inefficiencies; (b) high staff churn, more inexperienced staff and low staff morale; and (c) problems with hospital management and incentives from the centre. [14] This has been compounded by challenges with social care, with increasing numbers of people who are clinically fit for discharge remaining in hospital; the number of people who are in hospital facing delayed discharge has been above 20 per cent since January 2022. [15] There is also debate about whether growing regulatory demands are reducing the proportion of time spent on frontline delivery of care. Difficulties in increasing productivity can also be linked to the slow adoption of digital tools and technological solutions, as well as an outdated workforce model with limited incentives for delivery. However, evidence on the causes of recent NHS productivity trends is not fully clear.

The NHS Workforce Plan sets a target of between 1.5 per cent to 2 per cent annual NHS labour productivity increases over the coming decade, while the Health Foundation has estimated that funding for healthcare services would need to rise by 3.7-4.3 per cent to keep up with demand in the absence of productivity improvement – and public health, social care and health education funding by even higher rates. [16,17] For acute care services to keep up with rising demand indefinitely, without waiting times and waiting lists ever rising, would require an ever-growing share of national wealth being spent on health and care. [18] This is not sustainable.

Rather than just spending more money as revenue for day-to-day services and doing more of the same activity, the healthcare sector needs to do things differently and increase overall system effectiveness at keeping people healthier in the first place. Health and care leaders are conscious of the cost of inaction and look to plan services for the future, based on an understanding of the burden of disease in the long-term and not only the year ahead. This is not about changing how money is raised, but how it is spent.

The mission of integrated care systems

To reform how health and care services are provided and make the system more financially sustainable, parliament has created 42 integrated care systems (ICSs) in England. ICSs bring together all partners responsible for health and care, with integrated care boards (ICBs) responsible for commissioning NHS services. ICSs – as a collection of partners – have four core aims:

- improve outcomes in population health and healthcare,

- tackle inequalities in outcomes, experience and access,

- enhance productivity and value for money, and

- help the NHS support broader social and economic development. [19]

To achieve these goals, ICSs need to boost allocative efficiency – that is about spending money on services which improve health outcomes the most for every pound spent – by reducing demand for lower value-adding health care services and treatments in hospitals. This is strategically crucial to driving improvement and delivering better value given the pressures on the healthcare service. One of the ways of achieving this is to shift resources upstream towards primary and community care and earlier preventative interventions which in general, though not always, deliver better health value. By value in healthcare, we use the definition of ‘simultaneously the value delivered to the patient in the form of better health outcomes and the value delivered by the health system in terms of the most efficient use of society’s limited financial and other resources.’ [20]

If these services can prevent worsening ill health, they are a more efficient approach to improving health outcomes and limiting demand than more expensive downstream services. For instance, systems that invested more in community care saw 15 per cent lower non-elective admission rates and 10 per cent lower ambulance conveyance rates. [21,22] As a whole, a clinical intervention costs four times as much as a public health intervention, to add an extra year of healthy life, while 40 per cent of the burden on the NHS may be preventable through tackling the causes of avoidable chronic conditions. [23,24,25] Ensuring a healthy start to life through services for children and young people is also crucial to ensure they go on to have healthier lives as adults.

Crucially, this involves ICSs shifting their focus from just delivering healthcare to also taking responsibility, together with the patients, their family and communities, for improving health. Indeed, this was envisaged in the original 1946 Act that established the NHS, which defined the NHS’s roles as ‘a comprehensive health service designed to secure improvement in the physical and mental health of the people of England and Wales, and the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease.’ [26] Getting the best return on investment from preventative interventions will take some years and require some double running: meeting the healthcare demand from the population today, while preventing some of the demand for tomorrow. While preventative interventions are likely to reduce the rise in demand for healthcare services to lower than what it would otherwise be, demand is still likely to rise overall in any case.

It is therefore essential that ICSs also need to increase technical efficiency, delivering a higher volume and quality of activity in any setting at the lowest cost, to deliver timely, high-quality care for all patients. Much work has been done across the NHS to look at opportunities for greater technical efficiency – for example the productive ward work of NHSX’s Digital Productivity Programme and work carried out as part of the Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) initiative. [27,28] Both found that improvements to core processes can significantly improve technical efficiency in a variety of settings. With most NHS spend in the acute sector, there are likely significant opportunities to improve overall NHS productivity and financial performance by boosting technical efficiency in acute providers. However, technical efficiency opportunities in primary and community care settings should not be overlooked and merit closer analysis. Price-setting is also an important nationally-led component of driving technical efficiency, supporting local efforts. [29]

Digital technologies and data analytics are now offering further opportunities to improve efficiency and effectiveness of care delivery. Analysis of population-level data, including from wearables that can provide a constant stream of real-time health data, can help to identify households with the greatest need and enable local services to reach out to avoid likely hospitalisation to improve allocative efficiency. Meanwhile, investment in basic technology and artificial intelligence (AI) can improve technical efficiency through automation. [30,31] Digital transcribing on ward rounds can save doctors valuable time on ward rounds. Use of wearables for health monitoring can reduce staff time for health checks on virtual wards. Every £1 spent on technology can generate £4 in savings from time which is freed up. [32] Improving both allocative and technical productivity at the same time is essential, but a significant challenge.

However, there are obstacles to ICSs delivering such changes which sit outside of their own power to fix. As ICS leaders set out in The State of Integrated Care Systems 2022/23: Riding the Storm, systems need from central government: [33]

- far greater freedom and influence over how money is spent to drive transformation in care

- greater capital funding to improve estate and digital infrastructure [34]

- a workforce fit for the future [35]

- a functioning social care market [36] and

- more local autonomy to deliver this reform.

These obstacles, and the opportunities which could be unlocked from addressing them, were addressed in the Rt Hon Patricia Hewitt’s review of ICSs, providing a blueprint for the future. [37] While not a new idea, the review also showed there is substantial consensus across the health and care sector for a fundamental shift from a model of treating ill health to preventing it in the first place – a view also supported by think tanks of different leanings. [38,39]

The role of payments and incentives

The Hewitt review also identified that ICSs need to deploy the right financial incentives to drive the change they want to achieve, as has been done in other countries and the UK historically, stating:

“Financial flows and payment mechanisms can play an important role in ensuring improved efficiency in care delivery… current approaches are not effective in driving value-based healthcare and while payment by results can help drive activity in a particular direction, it is important to recognise that it needs to be adopted in the context of wider system reform, incentivising prioritisation of resources on upstream activity.

“Many health systems in other parts of the world, including those that are entirely or largely taxpayer-funded, are developing payment models that support and incentivise a focus on health. Meanwhile, NHS funding remains over-focused on treatment of illness or injury rather than prevention of them and ICS partners struggle to work around over-complex, uncoordinated funding systems and rules in order to shift resource to where it is most needed. There are lessons from other systems that we should draw on.” [40]

The Hewitt review recommended that government and ICSs consider alternative payment mechanisms, “drawing upon international examples as well as local best practice, to identify most effective payment models to incentivise and enable better outcomes and significantly improve productivity.” In particular, this, according to the review, should consider: [41]

- incentives for individuals or communities to improve health behaviours

- an incentive payment-based model - providing payments to local care organisations (including social care and the VCFSE sector) to take on the management of people’s health and keep people out of hospital

- bundled payment models, which might generate a lead provider model covering costs across a whole pathway to drive an upstream shift in care and technical efficiency in provision at all levels

- payment by activity, where this is appropriate and is beneficial to drive value for populations.

Financial flows within the NHS are fragmented and work against integration. The different parts of the NHS, primary care, community care and hospital care are not financially incentivised to work better together. The financial system does not allow all partners within an ICS to benefit from returns from investments in another part of the system, disincentivising some cost-saving investments. Because the savings are in a different part of the financial system than the investment, ICSs are not able to invest to save and improve health while increasing their long-term financial sustainability. Given the separation of financial systems for the NHS and social care, this makes real integration of health and care services difficult.

To that end, this discussion paper considers learnings from the use of payment mechanisms in this country and internationally and makes three proposals for changing payments for healthcare services and incentives in integrated care systems. In doing so, it takes account of how payment mechanisms in different sectors of the NHS (such as primary, community, acute) interact with each other to shape the overall behaviour and performance of the NHS. The paper does not consider the prices paid for services under different payment mechanism options, noting that international analysis suggests that national price setting is an important driver of technical efficiency. [42] It also does not consider payments for individual NHS staff and the public, although these are areas which merit further exploration.

The paper aims to reflect honestly on the advantages and disadvantages of different payment mechanisms, recognising that there is rarely consensus in the sector on an ideal type. It is intended to be the start, not the end, of a conversation leading to more radical change over the next two to three years. ICSs – that is integrated care boards, NHS providers and other partners within systems – should work together to consider the best payment mechanisms for their local circumstances.

Methodology

The proposals, reflections and case studies in this report have been developed in consultation with an expert working group, made up of system and finance leads as well as subject matter experts, and in collaboration with KPMG. Adult social care, community and primary care stakeholders were also interviewed and engaged throughout the research process. Desk research and a literature review complemented the findings from the working group and stakeholder interviews.

Domestic context: the current NHS Payment Scheme

NHS payment mechanisms have evolved significantly over the past 20 years in England, due to wide ranging reforms as well as incremental adjustments. Historically, before those 20 years of reforms, block contracts were used to commission community and mental health services. Primary care is funded through a mix of capitation payments and quality incentives. Payment by results (PbR, also known as payment by activity or activity-based payment) was implemented in the early 2000s in the acute sector to tackle long waits for elective care. In this case (and ever since), ‘results’ have been defined by the volume of activity, not health outcomes. Over time, the payment system evolved, moving towards a blended system that was upended by emergency arrangements during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Today, NHS England sets out payment rules in the NHS Payment Scheme, a statutory requirement of the Health and Care Act 2022, specifying payment mechanisms and payment prices. iii For payment mechanisms, the current NHS Payment Scheme for 2023–25 requires:

- aligned payment and incentives (API, a type of blended payment) for contracting healthcare services over £0.5 million delivered by NHS trusts and foundations trusts

- low volume activity block payments for services less than £0.5 million delivered by NHS trusts and foundations trusts

- activity-based payments for services delivered by other providers for which national unit prices (tariffs) are set

- local payment arrangements for services delivered by other providers where no national unit price exists. [43]

Crucially, within API payments, the scheme specifies (a) activity-based payments for elective care delivered by secondary care providers and (b) fixed block payments for community providers and non-elective activity delivered by secondary providers.

The 2023-25 payment scheme does permit that alternative local payment arrangements can also be made for services delivered by NHS trusts and foundation trusts with approval from NHS England.

The present scheme – specifically the two components within API – has been designed to align with the Elective Recovery Fund (ERF), with payment by activity incentivising higher volumes of elective care activity from NHS secondary care providers and independent providers to reduce the elective care backlog.

As set out below, while this may incentivise a higher volume of elective activity to help address the elective care backlog (although evidence is mixed and there are system, workforce and infrastructure constraints), it primarily incentivises more expensive, downstream interventions, accelerating an ever-increasing share of the NHS budget going to the acute sector rather than the more preventative interventions ICSs have been established to achieve. New payment mechanisms may better enable the delivery of ICSs’ wider goals.

What should payment mechanisms achieve?

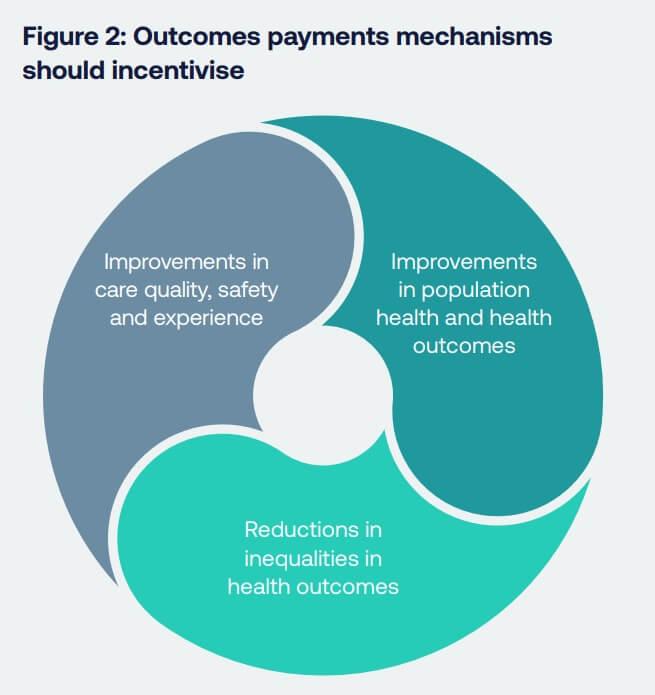

Given the four core purposes for ICSs and the challenging context, the key outcomes payment mechanisms should seek to incentivise include:

- Outcomes: Improvements in population health and health outcomes – reducing mortality and increasing quality-adjusted life years.

- Quality: Improvements in quality, safety and experience of care in all providers – including access to care and user satisfaction – with a particular focus on people living with long-term conditions.

- Equality: Reductions in inequalities in health outcomes, using resources to target the most at-risk populations, communities and areas, within existing funding envelopes.

To deliver improvements in the three areas outlined above, there needs to be a step change in allocative efficiency – where money is spent – to ensure a focus on those approaches which deliver the greatest healthcare value. This means a ‘left shift’ or ‘upstream shift’ to approaches to prevent ill health in the first place (addressing the wider determinants of health, supporting improvements to health behaviours) and to earlier intervention for those with disease, through better primary, community and social care.

There also needs to be improvement in technical efficiency to look at the costs (or resources required) of delivering care where there are significant opportunities to deliver care in more effective ways across all service areas (including primary, community, mental health and acute care) in order to deliver the maximum high quality activity per pound spent. Improving both allocative and technical efficiency is essential to achieving a more financially sustainable NHS.

Improving health outcomes

Improving health outcomes (improving quality and length of life) is ICSs’ first purpose. The NHS Long Term Plan set out particular priorities to improve health outcomes for areas such as cancer, mental health, dementia, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, among other areas of care and targeting groups such as children and young people. [44] Improving health outcomes will require improving care quality, care timeliness (covered by allocative efficiency, below) and core determinants of health (including supporting people to live healthier lives and make healthier choices).

While NHS and local government partners can play an important role in addressing the wider determinants of health, many such determinants are shaped by other areas of public policy (such as welfare, housing and education services) outside of ICSs’ control. Addressing the wider determinants of health will therefore require an integrated approach from national government.

Improving care quality

Improving care quality across all care settings is vital to improving health outcomes and patient experience, including waiting times. Since 1989, there have been several attempts to improve health outcomes and to improve care for people with long-term conditions (such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework, QOF). While there have been some significant improvements in the management of some conditions such as cardiovascular disease in recent decades, there continues to be high levels of variation in quality of care in many areas, and considerable variation in resulting demand for acute care. iv The Long Term Plan included targets to reduce certain waiting times, but the COVID-19 pandemic has inhibited progress.

In particular, the rising number of patients presenting with long-term conditions is contributing to poorer patient outcomes and an increase in economic inactivity (a challenge government is looking at through the Major Conditions Strategy). [45,46,47] Earlier interventions are required to prevent conditions worsening, social prescribing to stop conditions from developing, and more healthcare at home and in the community to support people to live with their conditions. As one in four adults has at least two health conditions, rather than treating each condition separately, services need to be integrated so patients can be treated holistically. [48]

Reducing health inequalities

The 2010 Marmot Review drew attention to the issue of rising health inequalities – reducing health inequalities is now one of ICSs’ four core purposes. [49] As well addressing the wider determinants of health, reducing health inequalities requires improvement in access to services (including proximity of local services, opening times, transport to services) and analysis of population health data so resources can be targeted at groups most in need. NHS England has developed the Core20PLUS5 approach to support ICSs efforts to define target populations and accelerate improvement to reduce health inequalities. [50] Sir Michael Marmot’s work describes a continuous gradient of health inequality to which proportionate universalism is often an appropriate response.

Boosting allocative efficiency

Improving allocative efficiency is crucial to helping address many of these objectives, including improving outcomes and financial sustainability. This is central to the mission of ICSs which seek to provide their populations with the right care, in the right place, at the right time. Increasing length of stay in acute beds, and mental health and community inpatient units, is linked to a range of factors, including the provision of social and community care, and drives up costs with a negative impact on patient outcomes. [51,52,53] Too many people are attending A&E or being admitted to hospital who could be better cared for elsewhere. There are significant productivity gains from avoiding urgent care admissions and managing these in different settings.

This contributes to the NHS spending an increasing proportion of its overall budget on acute care. [54] NHS spend on acute care increased by £10 billion in real terms (17 per cent) between 2020/21 and 2021/22, now accounting for over half (53 per cent) of total system spend. v Since we know that spending on public health, primary and community care has a greater correlation with economic growth (every £1 spent correlated with £14 in gross value added, GVA, to the economy), than spending on acute sector healthcare services (correlate with £4 in GVA), supporting a leftward shift in resources may also help to improve economic growth.

There has already been much positive progress in primary care to expand capacity and integrate care, with a growth in multidisciplinary team working and associated increases in consultations and consultation rates, and boost secondary prevention.55 However, despite the introduction of primary care networks, structural reform of primary care has been slow with still high variability in quality of care, access to care, resulting demand for acute care and the way practices are organised, with many as yet not able to deliver the scale of change set out in the Fuller stocktake of 2022. [56] More substantive change will be required – accompanied by increased proportion of spend on primary and community care – if improvements in health outcomes and associated reductions in acute activity are to be seen.

Alongside this, ICSs also want to put more resources into primary prevention, that is taking action to reduce the incidence of disease and health problems within the population, either through universal measures that shape the wider determinants of health (such as lifestyle risks) or by targeting high-risk groups. This can include addressing health behaviours such as smoking cessation services, promoting physical activity and deploying health interventions such as effective vaccination and screening programmes, to prevent and identify ill health in the community. Some of these services are commissioned and delivered by the NHS, others by local government partners within systems. Some are going further and considering the NHS’s impact on air quality and the climate.

Boosting technical efficiency

Technical productivity remains a significant challenge for ICSs with considerable opportunity to improve processes to boost output. For example, operating theatre throughput remains highly variable, with considerable late starts and early finishes resulting in fewer patients being treated; A&E throughput has slowed despite increasing resources and flat demand (though complexity has increased), length of stay has increased considerably despite strong evidence demonstrating the negative impact of longer stays. vi

Similar challenges occur in community care, with variable numbers of contacts per whole-time equivalent and in community mental healthcare where despite significant increases in workforce, activity has not kept up and similarly lengths of stay in inpatient units are highly variable. [57] Together, this results in considerable waste with resources being tied up in existing models of care rather than being refocused on improving health through a greater focus on prevention and primary care. The 2016 Carter review estimated that by reducing unwarranted variation, particularly in clinical services, at least £5 billion of savings could be made annually in acute hospitals. [58] There are also significant opportunities from a big expansion in the use of virtual wards. [59]

Example models of care to incentivise

ICSs are already making progress to achieve these aims and there are examples of effective services and behaviours across the country.

Case study: Addressing the wider determinants of health – healthy homes in West Yorkshire vii

West Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership is investing £1 million to help keep people warm this winter, so they can live long, healthy lives. In West Yorkshire, around 169,000 households cannot afford to keep their home at the temperature required to keep people inside warm and healthy.

In response, NHS West Yorkshire Integrated Care Board created an affordable warmth web page that collates resources available to offer support, whether that be providing details of organisations offering expert advocacy or signposting to possible grant-funding opportunities. Resources include information and guidance on how affordable warmth affects children and are also accessible in easy-read format. The board has also produced an infographic aimed at health professionals visiting people at home. The purpose is to support colleagues in identifying the signs of fuel poverty and support people to seek help.

Case study: Healthier Wigan viii

The NHS, local authority and other partners in Wigan are working together in the Healthier Wigan Partnership to make health and social care services better for local people. The partnership focuses on preventing illness by joining health and social care services together. For example, an integrated discharge team helps patients to be discharged directly home from hospital, rather than into residential care. The service also provides referrals to services that support isolated people to connect with their local community.

Case study: Frimley frailty community response service – implementing a hospital at home service to reduce hospital admissions for frail elderly patients [60]

Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust set up a hospital at home and urgent community response service, to improve the quality of care for elderly frail patients and reduce unnecessary and lengthy hospital admissions.

Deconditioning in older people with frailty may start within hours of them lying on a trolley or bed, with up to 65 per cent of older patients experiencing decline in function during hospitalisation. Many of these patients could prematurely end up in a care home because of deconditioning and the loss of functional abilities in hospital. Hospital admission avoidance in this group allows independence and promotes mobility.

To address this, the trust developed into a hospital at home service, including geriatricians assessing and delivering intravenous therapies, bladder scans and electrocardiographs using their access to a shared patient records between hospital and GP. The service has now evolved into a 12-hour emergency community response, operating 8am-8pm. With the ambulance service, it has developed a ‘call before you convey’ model whereby if a patient has had a fall or is confused, the hospital at home team is contacted by paramedics and attends to the patient directly. When ambulance services are under pressure, the hospital at home team may be able to get there faster than an ambulance, in which case calls are diverted to the team, so the most prompt response is achieved.

The urgent community response service between April 2022 and March 2023 saw a total of 2,933 accepted referrals, with patients commonly requiring urgent catheter care and end-of-life support or having suffered from falls, reduced mobility/function, and decompensation among others. The virtual frailty ward service during the same period saw 1,429 patients being accepted onto the hospital at home service. A service that led to a total of 1,266 avoided admissions across the 12 months.

Case study: Getting frailty patients home earlier – virtual wards in North West Anglia [61]

Eligible frail patients who would otherwise have needed to be kept in hospital are being supported at home by a multidisciplinary team. This is reducing their length of stay in hospital or, in some cases, avoiding the need for hospitalisation altogether, but ensuring they still get the same standard of care at home. Cambridge and Peterborough Integrated Care System has funded the Greater Peterborough Network (GPN), a federation of over 20 GP practices, and the North West Anglia Foundation Trust to run the service.

This frailty virtual ward model was launched in December 2022, starting with lower acuity patients and with the intention of spreading to those with greater needs. The aim was to offer something which was a true hospital at home – taking patients who would not normally have been considered suitable for discharge into the community. Patients who present at the emergency department (ED) are directed to the virtual ward, avoiding inpatients admissions but not ED admissions. Individual support is offered il to each patient and can include doctor input, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, with an assessment done in the home.

The team also looks at any other condition the patients have – other than the immediate reason for admission – and will try to bring them under control in this time. When patients no longer need to be in the virtual ward, they can be discharged back to the care of their GP and community nurses. Shared information between the frailty team and GPN was important to allow everyone to see the same information on the patient on single system.

Of the first 64 patients referred to the scheme, just eight were thought to be better off remaining in hospital. Those treated at home spent an average of 5.8 days on the virtual ward – time which would otherwise have been in hospital. Readmission rates have been in line with the in-hospital frailty ward at about 20 per cent. By reducing length of stay, patients are at lower risk of deconditioning if they are in their own home and it has freed hospital beds for those who can only be cared for in hospital. Use of block payments for non-elective care enabled the ICB, acute trust and GP federation to work together to innovate in service delivery, shifting resources from acute to primary care and achieve greater allocative efficiency. The number of virtual ward beds has been expanded to help alleviate winter pressures.

Case study: Lancashire Falls Response and Lifting Service – reducing avoidable hospital admissions

Technology enabled care providers, responders, two-hour urgent community response and ambulance services in Lancashire and South Cumbria are working together to ensure vulnerable people get the most appropriate support in the right place while reducing pressure on frontline services.

Between April 2022 and November 2023, falls services within Lancashire responded to more than 20,000 falls-related calls of which 74 per cent were lifted successfully. Only 4.9 per cent of referrals were onward referred to either 111 or 999 following an unsuccessful lift. 18 per cent of referrals received from the North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) were referred back to the service.

A responder will usually attend within one hour and the average response time is just 25 minutes. The team are trained in injury assessment and the moving and handling of people. If they suspect an injury or feel it is unsafe to lift they will call NWAS. A mobile lifting chair called a Raizer is used to help the resident off the floor.

The service helps to reduce the discomfort and stress of those who have fallen in their home, as well as the demand on the NHS and NWAS. It also minimises the risks and impact associated with ‘long lies’.

The service is now receiving direct referrals from domiciliary carers who, when visiting a service user, discover they have fallen and just need assistance to get up. Referrals are also being received from care homes following a successful communications campaign.

Significant system savings are evident in a number of services across this pathway, from ambulance services, to emergency department attendances and hospital admissions. However, a key notable impact is for the end user. At a time of sometimes very long waits for lower acuity ambulance calls this service brings comfort to those who have fallen and are unable to get back up. Importantly it can prevent a non-injurious fall developing complications requiring hospital admission and potentially poor health outcomes.

Case study: Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust – early diagnostic and treatment of diabetes and COVID-19 [62]

Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust uses HealthIntent, a real-time integrated dataset, to better manage and identify people with long-term conditions, to intervene early, reduce the risk of deterioration and decrease unnecessary use of healthcare services. It has applied this to treating Type 2 diabetes and COVID-19. A diabetes dashboard analyses data from multiple health records, test results and other factors to identify residents most at and require a healthcare intervention. From December 2020, the tool was also used to identify residents most at risk from COVID-19 and to prioritise areas and populations for the vaccine programme.

Through the diabetes dashboard, 4,387 pre-diabetes patients were identified by practices in July 2021. Between July and September 2021, 143 went on to receive a diabetes test, of which 13 were diagnosed with diabetes. Eighty-two undiagnosed diabetes patients were identified by practices in July 2021. Between July and September 2021, just over a quarter (22) had a recent diagnosis of diabetes. The COVID-19 dashboard has provided data on vaccination uptake rates in different cohorts of Lewisham residents, and provided data from which bespoke interventions could be developed. Without alerts on low uptakes rates among certain cohorts, GPs and other system leaders would have less clarity over where to direct efforts to encourage vaccine take up.

Case study: Kent Enablement at Home Teams (KEAH) – enabling independence and reducing pressure on social care [63]

Nine Enablement at Home teams provide clinical support and advice to supervisors. The teams’ purpose is to identify how to reach the most independent outcome for the individual receiving services. They aim to empower support staff to take reasoned and insightful decisions and understand how to work with people to create personalised goals. Simplified and structured paperwork to complement a weekly review of service users’ progress ensures the right support is provided at the right time.

Improvements are driven by analysis of the recorded data, which ensures issues that could prevent people achieving their best outcome are reviewed at an area and county-wide level. The end results are a reduction in the number of care packages required. 83 per cent of people who go through KEAH leave the service able to live independently at home. For 2016 this has led to an approximate saving of £3.2 million on long-term support. In comparison to last year, an extra 520 people are expected to leave the service fully independent. The average amount of weekly support for those leaving the service with a care package has reduced by 40 minutes due to improved service user outcomes.

Case study: Sussex Pathfinder Clinical Service – reducing secondary mental healthcare admissions [64]

Pathfinder West Sussex is an alliance of organisations working together to enable people with mental health support needs, and their carers, to improve their mental health and wellbeing. It provides a pathway of mental health recovery support so people can move freely between services to get well and stay well.

The Pathfinder Clinical Service offers easy access to mental health support and helps to form a bridge between statutory and non-statutory services to improve people’s experiences. The service is co-produced and delivered by all alliance members including a team of people with lived experience. The Pathfinder Clinical Service has three key focus areas:

- Transition interventions (step down): Supporting people’s discharge from secondary mental health services. These time-limited interventions include a six-session transitions group based on Five Ways to Wellbeing.

- Protective interventions (step-up): Proactive interventions for those people using the Pathfinder services. There are four levels of intervention available according to a person’s need. These aim to prevent further deterioration of mental health and potential escalation to secondary care.

- Stabilisation interventions (step-across): Supporting access and engagement with other services such as substance misuse and primary care psychological therapies.

People who have been supported by the Pathfinder Clinical Service report better mental health and wellbeing; improved confidence, self-esteem and optimism; fulfilling and meaningful structure to daily routines; and improved social connection with others.

As a result of the Pathfinder Clinical Service, there has been a reduction in the use of secondary mental health services. In a three-month period (January to March 2017), 46 people were discharged from secondary care, which equates to approximately 184 people in one year. Over a 12-month period this would equate to approximate cost savings of £144,900.

Case study: Tower Hamlets Crisis House – reducing hospital stays through a community-based recovery model [65]

Look Ahead works with the East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT) to operate a Crisis House in Tower Hamlets. The Crisis House provides support for individuals who cannot be supported at home by the Home Treatment Team or for individuals in acute hospital wards who no longer require intensive in-patient support. Crisis House also supports hospital patients who are clinically ready for discharge but have ongoing housing issues or who are waiting for supported accommodation in the borough.

At Crisis House, individuals are supported through their recovery and given emotional and general living support. Emphasis is on engagement and identifying triggers for mental health relapse and exploring resolutions to the triggers. Staff also explore coping mechanisms that individuals can use at home and link them into other community services to keep them well on discharge.

People are given advice and support to develop daily routines and meaningful structure. The support is also focused on promoting independence. For some this may include assistance around finding or re-engaging with work, training or education. This comes in addition to support to reduce any dependency-related behaviours, and to enable recovery in future. The Tower Hamlets Crisis House has the capacity to support ten individuals who are experiencing a mental health crisis at any one time.

Through close working with NHS partners, and on-site clinical support provided by ELFT, the service aims to enable individuals to avoid or spend less time in hospital, consequently reducing pressure on NHS wards and freeing up supply.

For example, on average individuals stay 22 days compared to 41 days in acute hospital wards. Further, the Crisis House has on average 5.5 per cent lower readmission rates compared to hospital wards. The shorter stays and lower readmission rates translate to savings for the NHS due to reduced demand and pressure on NHS resources.

The Tower Hamlets Crisis House cost per person is £198 per bed day (including accommodation and support costs), over 45 per cent cheaper than an average hospital stay per night (based on NHS reference cost data). In 2022/23 Crisis House worked with 66 residents.

Case study: Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust – high intensity theatres [66]

Guy’s and St Thomas’ developed a super-efficient but safe programme to maximise the number of patients treated using high-intensity theatre lists, known as ‘HIT lists’. They focus on one type of procedure at a time, take place at weekends, and require careful planning to select suitable patients.

The team redesigned and created dedicated theatre lists to accommodate additional patients and maximise theatre usage. Through organisation and careful planning, they were able to increase productivity by reducing waste, strict case mix and careful planning. Several multidisciplinary meetings were required for each HIT list to select suitable cases, patients and team members and to plan the equipment and order of the lists. They include managers, administration staff, therapists, nurses, pharmacists, anaesthetists and surgeons.

To carry out the HIT lists, there was an increase in the number of anaesthetic, surgical and theatre staff to minimise the turnaround time between cases, making more time available for the surgeon to operate. Using two theatres and three teams meant the surgeon could go between cases without having to wait for the next patient. This allowed more patients to be operated in the same time-period.

Surgeons at Guy’s and St Thomas’ carried out a week’s worth of operations in one day to help reduce the surgery backlog. Eight men with prostate cancer underwent a robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy, which was the first time in the UK that one hospital has completed eight cases of this kind in one day. The trust has held over 17 HIT lists and treated 344 patients across eight specialities, including gastrointestinal, gynaecology, orthopaedics and ear nose and throat (ENT). The use of payment by activity for such care incentivises a greater volume of output using the hospital’s existing resources.

Such services and behaviours need to be upscaled and spread. While ICS leaders are already trying to bring providers together to achieve these aims and avoid siloed working, change remains very slow. Financial integration and stronger financial incentives could help to integrate services for patients and lead to better outcomes and more efficient care. An ideal financial system would incentivise those changes need to accelerate these efforts. Currently, too often the current system stops them.

Five types of payment mechanisms

Before considering which payment mechanisms could be best suited to ICSs in England, we need to briefly consider the existing types of payment mechanisms used for healthcare services.

Block funding

Block funding is the payment of a lump sum to a provider for a defined service or services, at regular intervals, regardless of the population served or the amount of activity undertaken. Block payments are often linked to an anticipated volume of output activity. These block budgets are currently used in community and mental health care and were widely used across all care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Block funding can allow providers the flexibility to choose where to spend money between services, including to move services leftward/upstream as necessary and improve allocative efficiency, particularly when used across different care settings. The administrative burden and transaction costs are low and the capped funding provides consistency for both providers and commissioners.

Financial risk primarily sits with providers, who do not receive additional funding when rising demand for care leads to additional activity (such as urgent and emergency care), although this is often mitigated through cap and collar arrangements. In cases of controlled demand (such as with waiting lists), the risk is transferred from providers to commissioners who need to pay irrespective of levels of individual provider activity. However, block contracts offer few incentives to increase volume of activity, quality or technical efficiency in these settings. [67] Block funding for services in specific settings can also drive siloed working, with little incentive to collaborate with other providers.

Payment by activity (PbR) and fee for service (FFS)

Activity-based payments see providers paid for each activity, for instance a hip-replacement, they provide to a patient. The incentive for an organisation that does more work is further funding for that additional work, leading to a higher volume of care to more patients (assuming prices are set at the right level) and encourage greater technical efficiency, as providers keep marginal gains from doing more activity for a lower cost (although maximum activity levels can be capped).

Payment by activity aligns with patient choice rules, as the money follows the patient to their choice of provider in the public or private sector (although there are disadvantages of this, for instance making it harder to for commissioners to prioritise patients with the greatest need and leaving public providers with the higher complexity cases with increased costs without additional income).

Evidence from England and internationally indicates that payment by activity can lead to reduced length of stay, reduced waiting times and reduced unit costs. [68] In England, the introduction of activity-based payment in the acute sector in the early 2000s, introduced at a time of long waiting lists, helped to encourage activity in hospitals and has driven improvements in throughput and productivity.69 The introduction of PbR was accompanied by higher than historical average growth in the budget of the NHS, compared to more recent growth in investment (with the exception of spending during the COVID-19 pandemic). [70,71] It was also facilitated by wider changes – such as the creation of foundation trusts and a strong regulator (Monitor), with considerable financial incentives such as being able to keep their surpluses.

However, without strong payment mechanisms to control demand (as increasingly exist in more active payor markets such as Germany and the US), there is concern that payment by results (PbR) incentivises additional low value activity – activity which may not be necessary or could be addressed in more efficient interventions. For example, it can incentivise providers to admit more people to hospital than is strictly necessary, carrying out lower value-added procedures when conditions could have been treated at a lower cost and with better health outcomes at an earlier stage. Payment for activity has not been adapted to encourage earlier intervention and prevention rather than more acute activity. [72,73,74,75,76] It does not necessarily incentivise coordination and integration with other service providers payment for activity therefore risks being a counter-vailing force against ICSs’ mission to shift resources to earlier, preventative, more cost-effective interventions.

Annual budget cycles undermine the incentive for additional activity as extra resource that has been earned is taken away from the provider organisation at the end of the financial year. Payment by activity has comparatively high administrative costs, although only a small proportion of the productivity opportunity, and may only incentivise more profitable, low complexity activity which may not always correlate with patient need. [77] Over time, adjustments to PbR have made it difficult to evaluate its long-term impact and some of the initial incentives for individual organisations have similarly changed. PbR has not been tested in England as a payment for non-acute providers.

To be successful, payment by activity needs strong commissioning skills to incentivise required activity, not low value activity. It also needs to be part of a wider strategy to move existing monies within a system. [78] Some argue there is still a role for PbR to eliminate the current elective care backlog, particularly given the substantive reductions in productivity and throughout (such as cases per theatre list, length of stay). However, it may not be effective without addressing wider system challenges (such as difficulties in discharging patients, particularly given capacity in the social care system), an increase in funding relative to demand and may be at odds with an emphasis on prevention.

Fee for service (FFS) has also been used in primary care over the last 20 years, with a focus on additional or enhanced services alongside capitation-based and quality payments. FFS tends to incentivise specific preventative interventions, for instance vaccinations, with a good margin on the tariff at the expense of a population health approach or general preventative activity.79 However, many countries used FFS to drive activity in primary care – Denmark, France and Australia being the notable examples. [80] Experience of using fee for service in general practice in Denmark demonstrates the importance of balancing fee for service with capitation in order to mitigate incentivising unnecessary activity.

Different international incarnations of PbR and FFS vary in the degree to which they differ or are similar, often in the extent to which they bundle or unbundle different the costs for each element of a care spell. However, both PbR and FFS have mainly been used to incentivise the number of existing ‘results’ and ‘services’. Both the names, however demonstrate that the financial incentives are for ‘results’ and for ‘delivering a service’. It is therefore possible to define a result or a service in a different way and pay for that. At the moment, PbR and FFS fund inputs rather than outputs and outcomes. It would be possible to define a ‘result’ or a ‘service’ through an output or an outcome rather than an input and incentivise those achievements rather than inputs.

Payments for quality and outcomes

Quality and/or outcomes payments incentivise improvements in the quality of care and patient outcomes. Outcomes-based payments can provide payments for different kind of results – not just outputs (ie hospital activity) but the outcomes (improvements in patients’ health) which are intended. This can allow providers to keep savings from making patients healthier when they spend less money on activity to achieve this result, incentivising both technical and allocative efficiency. It requires commissioners to be able to effectively measure agreed outcomes and use this to inform payments and future commissioning decisions.

Existing use includes the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF), a pay for performance scheme for primary care introduced in 2004, and Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) implemented in 2009, paying NHS trusts for specific deliverables. Best Practice Tariffs (BPTs) – with prices and payments reflecting the cost of best practice, rather than average costs of procedures and services – were also introduced in 2010 following the Darzi Review to try to reduce variation and incentivise best practice in four high-volume clinical areas. [81]

QOF financially rewards GP practices for meeting a range of targets in the delivery of care. In 2023/24, these covered four domains: maintaining disease registers; clinical - improving the management of chronic diseases; public health - addressing key risk factors to health and improving vaccination rates; and quality improvement – improving workforce wellbeing and addressing capacity challenges. [82] This therefore includes both outcome and output payments. An evaluation of QOF found that it had incentivised general practice to have a more organised approach to chronic disease management and incentivised some secondary prevention. [83] It has embedded behaviours in general practice linked to its incentives. Conversely, an evaluation of the abolition of QOF in Scotland observed reductions in recorded quality of care for most performance indicators, suggesting changes to pay for performance should be carefully designed and implemented. [84]

However, there is little evidence that QOF has driven a significant increase in primary prevention and public health activities in particular. Some GPs have criticised QOF for its increased administrative burden and its negative impact on providing person centre-care through the pursuit of a narrow set of process orientated, clinical quality indicators rather than patient outcomes. [85] To a certain extent, QOF may have led to an overly medicalised, mechanistic and transactional approach, which undermines integration. Additionally, QOF has often focused on output activity, not health outcomes, which limits innovation in service delivery to meet desired aims and the ability of general practitioners to consider the variety of drivers of health. The conclusion is process indicators in schemes such as QoF are useful only when they have been shown in randomised trials to be strongly and causally linked to important outcomes. [86] Of course, payment by outcomes relies on the availability of accurate data. This is already used to some extent for talking therapy services.

Consistent tinkering since QOF’s introduction and additional payment measures, such as the Impact Investment Fund (IIF) and PCN Direct Enhanced Service (DES), have reduced the evidence-based nature of many of the indicators and added complexity and bureaucracy which has hindered its efficacy. Various sets of data collation and reporting requirements are required to enable payments. While there are likely to be changes to QOF and the IIF which are (at the time of writing) currently being discussed as part of the 2024/25 GP contract and PCN DES, a revision of QOF might focus on rewarding population health outcomes and incentivising performance improvements above an established baseline, minimising changes and complexity, re-establishing the use of evidence based indicators. [87] Simplicity is a key lesson to help payment mechanisms lead to the desired behaviours. The GP Contract consultation process also highlights the value of co-creation to ensure payment mechanisms are effective in incentivising intended behaviour.

For CQUINs, evaluation suggests that the impact of CQUINs against desired results has been disappointing and the costs of the scheme outweigh the benefits.88 This is in part because the data needed to administer payments adds a significant administrative burden, particularly when the range of indicators for which payments are made proliferates. Potentially as a result, CQUINs are being scaled back in the proposed payment scheme for 2024/25. Using data from the established national clinical audit programmes may be option to consider. An early evaluation found higher support for BPTs than CQUINs among frontline clinicians who viewed it as evidence-based and with fairer payments.89 Evidence on its effects on quality and patient outcomes was mixed – the evaluation found some relative improvements but at the same time unintended consequences.

A quality-based payment mechanism focused on waiting times is being trialled in West Yorkshire (see case study below) to incentivise waiting list reduction. Use of a block payment for acute elective services, which is modified by rewards and penalties for beating or exceeding waiting times targets, across the provider collaborative, enables clinical leads to innovative in service design and potentially allocative efficiency. Meanwhile, the payment element tied to waiting times, a metric of quality, incentivises delivery on a key national priority. However, although an evaluation is still pending, it is not clear that this approach necessarily helps to drive technical efficiency.

Learning from local and international experimentation, any outcomes-based payment relies on the ability of commissioners and their providers to define and measure a set of clear indicators. This may involve a lengthy engagement process as well as an investment in the right tools to measure and analyse data and a transfer of risk from commissioners to providers (which should be backed up by appropriate reserves). These implementation costs should be considered but are likely to benefit from advances in data analytical systems now available. Additionally, any outcomes-based payments need to consider the size of the population cohort to avoid any cherry picking of patients with less complex conditions where outcomes targets could be more achievable.

Outcomes-based payments should cover as much of the care pathway as possible, ideally the whole pathway, to incentivise the most effective interventions. Different providers then have to collaborate to focus resources on the interventions, interventions which will be out of the immediate control of some individual providers. This shift in commissioning across pathways, rather than particular services, goes beyond financing to the wider commissioning model. It can be a crucial enabler of supporting a leftward shift to earlier, more preventative interventions and is an important consideration going forward.

Case study: Block contracts with penalties for long waits in West Yorkshire ICS [90]

To incentivise reduction of long-waits for care, West Yorkshire ICS is piloting a block payment model for NHS providers across the West Yorkshire Association of Acute Trusts provider collaborative, who can face rewards and penalties for treating or failing to treat long-waiters. Targets are agreed between the commissioner and providers, who face a £2,000 penalty for every 52-week waiter above their target number at the end of March 2024. Conversely, trusts that beat their target will receive a £2,000 bonus per patient, and there are no caps for under or over performance.

The aim is to drive a focus on long waits without losing the benefits of collaboration and clinical innovation that a level of fixed income had enabled. While PbR ties payments to specific units of activity listed in the national tariff, making it harder for providers to innovate in models of care, this model aims to prioritise helping patients who have waited longest. The block payment element of the contract has also enabled innovation in service model delivery that was disincentivised under PbR arrangements. At the time of publication, the pilot is due for evaluation.

Case study: Oxfordshire outcomes-based commissioning ix

From 2015 to 2020, a partnership of six providers including Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (lead provider), Restore, Response, Oxfordshire Mind, Elmore and Connection Support, provider mental health services in Oxfordshire through an outcomes-based commissioning contract.

The partnership aimed for people of working age using mental health services in the country to live longer, have an improved level of wellbeing and recovery, have timely access to assessment and support, maintain a role that is meaningful to them, continue to live in stable and suitable accommodation, have better physical health and for their carers to feel supported.

Evaluation of the measures agreed by the partnership found that the majority of the outcomes had been achieved and that physical health monitoring for mental health service users has increased. In addition to this, new services were created, joint working between providers improved and the voluntary sector had greater financial security.

Financial constraints in the local health economy and a rise in out-of-area hospital admissions created challenges for the partnership, particularly in delivering large-scale change in service provision.

Bundled payments

Bundled payments group together payment for multiple services, covering more than one element of care across all or some of a patient’s treatment pathway, rather than for each particular service along those pathways. [91] This incentivises providers to collaborate along a care pathway and consider the downstream impact of decisions to minimise complications and unnecessary or avoidable care. They can be used in different ways: for specific long-term or elective conditions, over a certain period of time (year of care for example) or for whole services (such as maternity or some types of orthopaedic services). Bundled payments sometimes make a portion of the payment dependent on achieving particular care outcomes.

Bundled payments can incentivise providers to focus on the lowest cost and highest impact interventions within a care pathway, enabling a shift towards more preventative and integrated care. This may also drive improvements in quality, for example by preventing avoidable complications, and productivity, with one or more providers focusing on the intervention with the highest added value. [92] Bundled payments are most effective for easily defined pathways with clear measurable metrics.

Strong commissioning can mitigate some of the risks associated with this payment mechanism. Delineating what is and is not included in a pathway can be challenging, particularly when taking into account chronic conditions and comorbidities. What kind of activity is incentivised through the bundled payment also needs to be carefully considered, with the potential for gaming and, for example, avoidance of necessary specialty care or encouraging unnecessary episodes of care. [93]

Case study: Bundled payments for hip and knee replacements and cataract surgery in Stockholm [94]

In 2009, the Stockholm regional government, which funds healthcare services for around 2.3 million people, implemented a bundled payment for cataract surgery and hip and knee replacements. Providers were paid single base price cross the pathway, including diagnostics, implants, surgery, postoperative care, rehabilitation and follow-up visits. They were also rewarded or penalised with up to 2 per cent of the payment tied to specific outcomes. Patients had a choice between public or private providers, who had to bear the cost of complications up to two years after surgery. Only patients without comorbidities could benefit from the hip and keen bundle, leading to some cherry picking.

Through these bundled payments, more care was shifted from the acute sector to specialty clinics which provided better value for money. Overall, cost per patient declined by 14 per cent for providers and 23 per cent for payors while also leading to a decline in hospitalisation, inpatient days and physician visits per case. For hip and knee replacements, complications decreased by 18 per cent, reoperations by 23 per cent and revision by 19 per cent. This payment mechanism was extended to spine care and a national value-based performance monitoring and payment programme.

Capitation and risk payments

Capitation payments are lump sums paid to a provider or group of providers for specific services per enrolled patients or target population. Payments are made on a per person basis. These can include a ‘risk weighting’ element, modifying how much is payments relative to the ‘risk’ of cost associated with the population, for example the age or level of deprivation of the patient population, with higher payments linked to higher risk.

Capitated payments can incentivise investment in early intervention and prevention to avoid worsening ill health and the need for more complicated and costly interventions, and give providers greater financial flexibility if providers can retain savings from avoided costs. [95,96] If the payment model ensures there is a ‘gain-share’ between providers and commissioners, this model incentivises providers to ensure that care takes place in the optimal setting and that preventative approaches are implemented. [97] Additional payments can be made to reward specific outcome targets. These benefits can be seen in capitated payment models internationally (see case studies below). Risk is shifted from payers to providers but also allows providers to benefit financially from preventing worsening ill health but retaining money where costs are avoided.

Today, general practice in England uses a type of capitation, with payments for core general medical services weighted relative to the number of patients registered with that practice (but with no risk-weighted element). [98] However, the current general practice contract crucially does not include a financial incentive for reducing downstream activity, unlike many capitation-based payment models in other healthcare systems. Other payments for general practice like QoF and IIF have, over time, become part of their core payments model and become increasingly complex, with a multitude of output and outcome metrics. The model has become distorted and does not capture key benefits of capitation models internationally. Additionally, given the decrease in the number of GPs and the overall increase in service demand, GPs in practice have little time to dedicate to prevention and wider determinants of health.

There are risks associated with capitated payments, including rationing of care, cherry picking the least complex patients and the duplication of payment by commissioners for the same service – ie paying a primary care provider to keep people well and out of hospital while at the same time having to incur the fixed costs of acute hospitals – and increased need for reserves for the commissioner. Single-year contracts also mean providers are unlikely to see cost savings in the short term so incentivising short-term cost savings instead of longer-term preventative activity. [99] Organising capitation around defined patient groups and population segments can help to mitigate the risk of cherry-picking, while clear standards for service quality should be defined. [100]

Case study: OptiMedis shared savings contract [101]

OptiMedis is a population-based integrated care model operating in parts of Germany. The OptiMedis payment system is based on a ‘shared savings contract’. x The contract is drawn between the integrated network on one side and sickness funds (payors) on the other. As part of this contract, positive differences between expected costs and the real healthcare costs of the population the network is accountable for are considered ‘savings’ and are shared between the integrated network and sickness funds.

The share of savings received by the integrated network is used to finance integration efforts, including performance bonuses and operations of the regional integrator. Any remaining profits are re-invested in the regional healthcare system.

To avoid an under provision of services to generate savings, there are minimum quality standards that need to be complied with. The payment system is therefore designed so that there is a financial incentive to invest in delivering high-quality, efficient, preventative care.

According to the OECD, this model of care is suggested to lead to an additional 146,441 life years and 97,558 disability-adjusted life years by 2050 in Germany. Over the same period, cumulative health expenditure savings per person are estimated at €3,470 in Germany.

Case study: ChenMed Risk-capitation funding [102,103]

ChenMed operates under the Medicare Advantage model in the US and aims to create financial incentives to keep people well and out of hospital. Organisations can bid for the money from Medicare, (run by the US Department of Health) to cover the cost of healthcare for people over 65 with complex health needs and/or high levels of deprivation, to look after populations – these would either be health insurance companies or health and care providers.

ChenMed receives upfront funding for the total annual cost of patients, with a small proportion allocated to administration functions. They are free to divide the rest of the funding as they see fit across enhanced primary care centres, a central office providing shared functions and external costs linked to acute care, specialist referrals and medications. ChenMed can keep all surpluses and fund deficits, which means they bear 100 per cent of the risk, particularly as they provide funding for all acute care and medications their patients receive.

The annual cost of a patients’ care is risk-weighted according to a range of factors, including number of conditions and age, and determined by evidence of a relevant diagnosis with the appropriate treatment in progress.

ChenMed focuses on improving patient outcomes and experiences and increasing care at home by investing in primary care and prevention. For example, they provide 20-minute appointments, onsite X-ray and ultrasound as well as interventions to address patient health barriers and needs such as social workers and cooking classes.

Despite similar complex health needs among their patients, ChenMed averages 1,324 inpatient hospital days per 1,000 patients over 65 compared to an average of 2,220 across Miami and 2,236 in England. This demonstrates the value of their preventative and proactive integrated out of hospital care.

See further examples in Appendix 2: Kaiser Permanente, New York State Medicaid and Saudi Arabia Health Sector Transformation.

Reflections on existing payment mechanisms

The combination of payment mechanisms now used in England (based on activity based for acute care, block for community services and capitation for primary care) means that more activity increases acute provider income but increasing activity in community and primary care increases costs but not income. With fixed budgets at system level, the net effect has been and is likely to continue to be an ever-increasing share of the total budget being spent in the acute sector at the expense of investment in primary and community care. It also provides little or no incentive for better coordination and integration of services.

While there is a rationale for this to help address the backlog of acute elective care in the short term, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent trends in acute productivity, it does not ultimately align with the mission of ICSs to manage ever rising demand for services by shifting resources to earlier, more preventative and cost-effective interventions. Innovative use of payment mechanisms, alongside other enables, is required to help support these longer-term policy goals.

Summary of payment mechanisms

The table below summarises the different mechanisms, setting out the pros and cons of each approach:

Payment mechanisms for ICSs: What should the NHS be considering now, next and in future?

Looking to the future, the NHS in England will need to consider what form of payment mechanism could best support ICSs to meet their objectives set out above and remove the barriers to tackling the challenges described. This paper sets out three potential models for consideration. These models have been proposed following discussion with the Payment Mechanism Working Group and following engagement with some NHS Confederation members, experts and wider stakeholders, as well as reflections on existing types of payment mechanism and international case studies which are highlighted in the paper. The models are presented to contribute to further debate and experimentation but are not intended to represent an ideal type nor a specific view on behalf of NHS Confederation members.