Key points

Neighbourhoods and communities are difficult to define and can range from a few houses to a population of around 50,000, but they are critical to the future of our health and wellbeing.

This report, alongside our case for change, outlines where we are now and what initial steps can be taken to create new, more effective and sustainable solutions for neighbourhood health.

Working at the neighbourhood footprint is not new but there is a long way to go across most parts of the country to create genuine neighbourhood health models. This means neighbourhoods harnessing the assets valued in a local area, with statutory services’ operating models proactively wrapping around those communities and their needs.

Integrated neighbourhood teams (INTs) play a part in bringing statutory services together to work more effectively with voluntary and community organisation and citizens, but this is only one part of a bigger model for neighbourhood health.

Integration isn’t always the answer. For community-led organisations, high levels of integration with statutory partners can risk breaking trust with communities, especially in deprived areas, where their value comes from not being part of a system that citizens feel they have been let down by previously.

This work requires a shift in funding, culture and service models at national, system and local level and the scale of challenge should not be underestimated.

Several core areas had the biggest impact on the ability to develop these models: Existing relationships; the variation/short-termism and often lack of funding; Leadership from within the community with management support to coordinate initiatives; Data sharing; Resilience of the voluntary workforce and ability to build share goal/purpose between organisations and the community.

There is a role for neighbourhood, place/system and national leadership in taking the initial steps to catalyse, nurture and help sustain neighbourhood health models. This report provides recommendations on how system/place can unlock capacity and capabilities in communities and neighbourhoods on how to harness local people and ideas for those delivering this change locally.

The government must recognise that the shift to a community-first approach is one of the most significant changes in the statutory sector. It means working within the existing systems that are set up to support this way of working but unlocking its ability to work in this way. The government must:

put neighbourhoods and devolution at the centre of the new ten-year plan for the NHS

reform payment mechanism in the NHS and local authority to create greater flexibility

reform the GP contract to enhance primary care’s role in neighbourhood health.

Background

Most of us can describe the neighbourhood where we live, but few of us would want to try to define someone else’s or what this might look like nationally.

When statutory services define neighbourhoods, they will generally describe areas which are just smaller sub-divisions of other geographies to which they relate, such as regions, counties and cities.

Within the NHS structure, integrated care systems (ICSs) can range from 500,000 to 3 million people, while ‘places’ are typically described as being at the 250,000 population level.

The next level down in current NHS structures is often the primary care network (PCN), including groups of GP practices designed to cover around 50,000 people, and now strongly linked to the concept of integrated neighbourhood teams (INTs), which are due to be rolled out across England.

However, even 50,000 people is much larger than many of us would associate with a neighbourhood. The reality is neighbourhoods are different everywhere, defined by a combination of political, socio-economic, historical and cultural factors that are as diverse as our local communities and which often defy geography.

Within and across neighbourhoods live those communities, whose identity is often even harder to define, with an individual or family potentially having more than one identity that can change and evolve over time.

The fact that neighbourhoods and communities are difficult to define does not mean that they are not critical to the future of our health and wellbeing.

About this report

Our case for change makes the argument that only by changing the nature of the relationship between statutory services, neighbourhoods and communities will we have any chance of sustaining our health and care systems, closing the gap on growing population inequalities, and achieving our bigger aspirations for a better society.

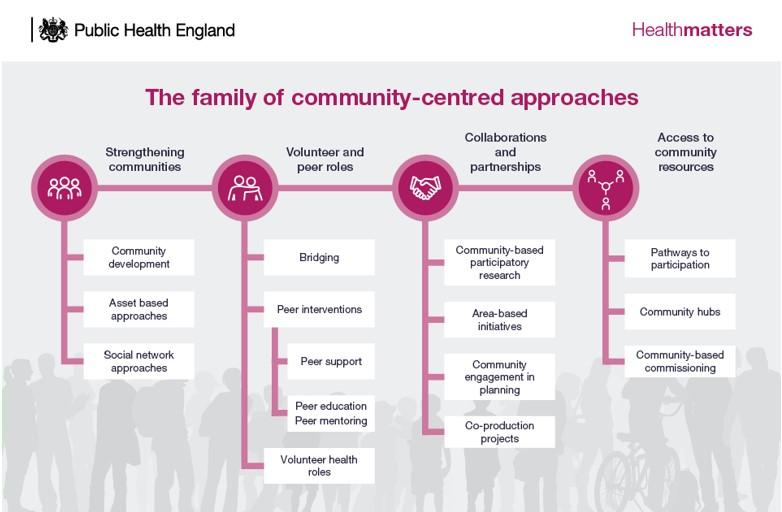

As part of this work, we have looked at the evidence for neighbourhood and community-based efforts to improve health and wellbeing. We have found a spectrum of different types of interventions, from those developed within and by statutory bodies, to those that have arisen entirely within communities themselves, often in a conscious response to gaps within, or perceived failings of, the local services upon which all communities rely.

This report shows how we can learn from these experiences to build a better set of co-ordinated, neighbourhood-based responses to improving health and care, working together.

Statutory services have access to resources, infrastructure, people and scale that community groups often lack. This includes in and around the most deprived communities where there is the greatest need, but which have also often experienced the greatest degradation of community assets in local years.

Communities in turn bring their own assets, insights, understanding and lived experience; a sense of ownership, continuity and a rootedness which, for reasons including the need for efficiency, consistency and scale, have long since been lost in many of our public service delivery models.

Bringing together these two powerful forces for good to advance the health and wellbeing of a neighbourhood is not easy.

Our report supports the Darzi review findings that INTs, in a statutory context. are essential to health and care services being more proactive, preventative and person-centred. This requires organisations within neighbourhoods to be able to integrate their structures and relationships.

However, a commitment to integration with community-led organisations and assets needs to be carefully considered.

Part of the power of communities is that they have freedom to shape how they respond to local need in a way statutory services do not. For people in communities, they often have a unique relationship with their community that would be very difficult for statutory organisations to replicate. We must not lose the identity and role of community-led initiatives by creating one homogenous whole, but instead find opportunities to work together for a shared purpose, unlocking skills, insight, experience and resources across a neighbourhood.

Approaches that are genuinely community-led, but supported and enabled by co-ordinated public sector action, can successfully mobilise individual and shared assets and deliver better outcomes that could not be achieved by either partner alone.

This report speaks to how professionals from within the NHS, local government and wider public services can step jointly into the neighbourhood space.

The failure to collaborate effectively around neighbourhood needs drives demand across the whole health and care system, not only in acute hospitals but in primary, community and mental health services and in adults’ and children’s social care. It results in people with serious health conditions presenting later, with more severe needs and worse outcomes, as well as being unable to gain meaningful employment or live independent and fulfilled lives.

The neighbourhood is uniquely placed to support health creation once the required enablers are in place because it is the nodal point where our efforts as statutory services come together with the communities we serve.

We’ve seen through our research the transformative power of working together at a neighbourhood level and the many varied forms this can take. At the heart of any effective and sustainable neighbourhood effort are relationships between statutory and non-statutory partners that unite to drive towards a shared objective, with mutual respect and acknowledgement of the role and impact each has. Where successful, this alignment is often transformational. Improving health outcomes and reducing pressure on health and care services. .

The UK Government has set an objective of transforming the NHS into a ‘Neighbourhood Health Service’ where better coordinated action on preventing ill-health and proactively caring for those who need help is delivered closer to home. It supports the wider fourth purpose of ICSs in underpinning not just the health of our whole population but through this supporting the growth needed to invest sustainably in better public services.

The first step is to understand that this is not just about where and how primary, community, mental health and specialist clinicians collaborate with each other and other statutory partners, but how we take this opportunity to reframe relationships with neighbourhoods and communities as a whole.

This report follows from and complements The Case for Neighbourhood Health and Care, which describes the overall case for change.

It makes recommendations, informed by our literature review and case studies for stakeholders working at all spatial levels, from national policy to local delivery.

We have found that a different change model is required to many of those we are used to applying to health and care. This is an approach that can catalyse, nurture and sustain neighbourhood working, through being adaptive and willing to cede leadership. Without a new approach at a national and local level, isolated pockets of good work and practice are unlikely to be sustained, to scale or spread.

While people do not want to be ill, incapacitated or hospitalised, we will always need high-quality specialist services, institutions and professionals to respond to their needs. However, the consequence of a failure to build on existing community initiatives that support people to stay healthy and well, living safely and independently in their own neighbourhoods and homes, is that no amount of investment in public services and institutions will ever meet projected demand.

The approaches highlighted in this report speak to simple and non-medical interventions at a local or hyper-local level, but have a direct impact in future on the performance and sustainability of urgent and emergency care, planned care and social care, as well as the experience and outcomes of the individuals involved.

The following sections include descriptions of the experiences of communities and their partners, common barriers to and enablers of better neighbourhood working, six principles to support this, and practical recommendations for those working at all spatial levels on scaling the impact and benefits of neighbourhood based, community-led approaches.

Our recommendations link to six key principles of effective neighbourhood working as identified from our research:

- Listen to understand.

- Build relationships.

- Empower neighbourhoods.

- Create common purpose.

- Embrace diversity of approach.

- Think and act sustainably.

What is happening now?

Neighbourhood working is not new.

We live, work and play in neighbourhoods and much of our daily experience is shaped by them. It is not surprising that focusing on how we work together better at this level, has been the foundation of many effective and innovative responses to local needs across health and care and beyond.

Neighbourhoods and community-led responses took on particular prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, but effective interventions at this level pre-dated this experience and continue in a diversity of forms today. The government’s shift to a neighbourhood health service is a cornerstone of its new health policy but also builds on earlier work within the NHS to try to develop better co-ordinated, more local approaches to health and care delivery, including the concept of INTs.

Our evidence suggests that meaningful involvement from across a range of different groups and organisations is key to developing a deep and shared understanding of local health issues and inequalities and an impactful response to these. Achieving this in practice is complicated and requires navigating a range of issues, from how neighbourhoods are defined, to how resources are allocated and how decisions are made.

We have found that the there is no single definition of a neighbourhood across the case studies included in our research.

Local people define their neighbourhoods in ways that reflect the geography, history and culture of where they live, as well as political and socio-economic factors.

Statutory services define neighbourhoods using boundaries such as the shared footprints of GP practices constituting a primary care network, or the wards of a district council, which often only coincidentally represent the neighbourhood that residents identify with. And as a result, population sizes vary greatly from potentially a single row of residencies with up to 50,000 people or more.

In urban areas a neighbourhood may cover a small geographical area, whereas in rural areas, where the population is dispersed, the geographical footprint may in some cases be much larger.

From our case studies, literature review and wider work on community development, it is apparent that enabling a degree of self-determination of neighbourhoods is important to supporting authentic community engagement. But, the case studies also suggest that it is possible for statutory-defined neighbourhood work to still achieve positive outcomes.

In some examples, NHS and local authority partnerships often constructed at a place level have combined statutory-defined boundaries with a flexibility on how smaller-scale neighbourhood work happens and is supported within these boundaries. What is important in all these cases is not necessarily spending significant time and resources on definitions, but rather to acknowledge and manage the potential tension between how systems might define neighbourhoods and how communities and people define their neighbourhoods early on.

Where this tension has been successfully resolved, it has required an openness from statutory partners to work in ways that are as flexible and influenced by community preferences as possible, alongside a recognition from non-statutory partners that this may need to be balanced against what is possible and pragmatic from a statutory perspective.

Working at a neighbourhood level is key to understanding and responding to specific population health issues and inequalities, but it can be complicated by the need to encompass a diversity of local communities with different characteristics, expectations and needs. Some examples of successful neighbourhood working we observed were established specifically to bring a set of local communities together, rather than to continue to work with a disaggregated group of different faith, cultural or interest-based groups.

Neighbourhood working as described in this report can be conceptualised in the middle of a spectrum that ranges from wholly community led to wholly statutory led. This is not to say that other models and interventions are not good examples of neighbourhood working, but many of the strongest examples of sustainable and impactful work sit somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. This is particularly true in more deprived areas, where without statutory support the assets and infrastructure to enable communities to support and enhance their own health and wellbeing may simply not exist, irrespective of the commitment and energy of the local population.

In the aftermath of the Fuller stocktake, endorsed by the chief executives of NHS England and all 42 ICSs, there has been a particular focus on integration at the neighbourhood level within the NHS. This is expressed in the idea of an integrated neighbourhood team (INT) covering health and care professionals working together with voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations and other partners to improve population health outcomes.

Integration in this context is often driven by a desire to provide a more joined-up, efficient and effective approach to prevention, access and complex care.

However, our work suggests that when it comes to working with communities and community groups themselves, positive outcomes can often be achieved simply through better understanding, collaboration and connectivity, without formal integration of teams, funding and approaches. This may also provide lessons for statutory partners looking to enhance joint working on a local and hyper-local scale.

In practice, neighbourhood working generally involves a range of different activities that in some cases are about formal integration and in others are more about cooperation and coordination. This more nuanced approach is a source of strength in many examples. Tools such as the spectrum of collaboration can help to support situating arrangements in terms of local objectives and needs, and what the best response to these is likely to be.

Source: Collaboration Spectrum Revisited (tamarackcommunity.ca)

It is possible to have integrated outcomes, shared between partners, without integrated delivery of the steps to achieve those outcomes. None of our case studies for this report exhibited full integration of statutory and non-statutory services, and we heard in some examples how full integration would likely have led to the models being less effective. We also heard of models where non-statutory services have been able to reach communities and build trust with neighbourhoods in part because they are not seen as being ‘from’ statutory services. Integrating such services more formally with statutory partners would risk breaking this trusting relationship and severing connections with the communities they serve, making future relationships harder to build. This applies particularly to communities where people feel poorly served by statutory services in the past, and therefore currently have a high-level of distrust of these services.

The level of integration in and across any model will need to be defined and guided by the outcomes being sought and needs to be considered carefully as a means to an end, and not an end in itself.

What makes this work?

The case studies produced as part of compiling this report, and the wider literature review, offer strong examples of people working to transform health and wellbeing, reduce health inequalities and deliver stronger, happier and healthier communities.

There are several common success factors:

- Trust. Investing time in building relationships and trust between communities, VCSE organisations and statutory partners. This is particularly important where residents have had poor experiences and are as a result understandably reluctant to engage with statutory services, and more likely (at least initially) to become involved with community or VCSE-led initiatives. Developing an open, accessible and non-judgemental culture where everyone feels welcomed, able to share their story and bring their perspective was seen to be vital. This can require partners to step outside of their organisational comfort zone, enabled by a level of support and permission from senior leaders to do so.

- Applying existing methodologies and ways of working. A range of methodologies to support community development and neighbourhood-based working were identified, which are described further in this report. A ‘mix and match’ approach to the choice of methods had been taken by different sites, with a strong degree of pragmatism and a willingness to learn and adapt to the local context and needs. Where available, the use of more local-level data overlayed with community insight enabled a more effective understanding of neighbourhoods and their needs.

- Ongoing co-design and meaningful involvement. Listening to and co-designing solutions with community members helped to build trust and mutual respect. It strengthened the impact of interventions, as they reflected local expertise and insights into opportunities, issues, barriers, enablers and assets. This led to more bespoke interventions with buy-in from residents, which were more impactful and more likely to be sustainable, not least because local organisations were likely to be involved in support and delivery. It was important that this focus on co-design was maintained over time, to ensure interventions continued to respond to evolving neighbourhood assets and needs.

- Building on a foundation of a shared purpose and common goals. This meant agreeing a shared purpose and common goals between partners at the outset, alongside a process for tracking progress and impact against these goals. Where possible, this helped to develop an evidence base (in turn, enabling better access to funding), to build momentum, and to provide a solid foundation for future collaborative working within neighbourhoods.

- Resource allocation. Devolution of funding, responsibility and other resources to neighbourhoods was identified as a key facilitator of the development of new local delivery models. This often requires a high degree of confidence on the part of funders that investment will return long-term benefits, as well as a willingness of community leaders and VCSE organisations to place trust in statutory partners. There was a need for bravery, a willingness on all sides to take on a degree of risk, and for building bridges between communities and services, particularly in areas where relationships had previously been poor. However, without negotiating these complexities, many successful schemes would never have got off the ground or been able to impact in the way they have.

- Flexible, long-term funding. The funding required to establish and operate neighbourhood working is rarely large in the context of health and care budgets. Nonetheless it is a key enabler of better neighbourhood working and to be effective requires a degree of flexibility and the ability to predict flows over the longer term. Providing flexible funding enables neighbourhoods to adapt and respond to needs as they arise and manage challenges such as increasing operating costs as interventions scale. Long-term funding provides the foundation and confidence for all partners to invest in the model, while being assured that the investment in relationship building will not be undermined by a lack of future funding. Locally sensitive commissioning that understands the dynamics of working in this way will be critical if the benefits of neighbourhood working are to both spread and be sustainable.

- Collaborative and stable governance. Developing and implementing clear and inclusive governance structures, which involve stakeholders from across the neighbourhood including community members / residents, VCSE and statutory representation, was important for the sustainability, adaptability and effective co-ordination of efforts across a neighbourhood. ‘Governance in depth’, bringing in a range of people from across and within partnering organisations, and not relying on the motivation or goodwill of a handful of individuals, was a core part of ensuring local work could survive a change of personnel and continue to deliver impact over the longer term.

- Management and administrative capacity. While much of this work is around building on the existing commitment, energies and assets, bringing different organisations and cultures together takes time and capacity. Without investment in support to bring people together, co-ordinating efforts, dealing with administrative and other issues that arise, and evidencing success in a way that supports future funding, both the scale and pace of change are likely to be severely limited. How statutory partners provide this support to communities and smaller VCSE organisations, in a way that is enabling and empowering, is key. In reality it was relatively small investments that were needed to create the momentum to unlock and sustain neighbourhood working. Such efforts produced significant impact for both the communities themselves and the statutory partners working with them.

- Access to community infrastructure. Having a physical ‘place to be’, alongside various other elements of community infrastructure, including access to community groups and social networks, was a key enabler to successful neighbourhood working. Where this infrastructure is available, it provides the space for people to collaborate and can also be a driver of civic pride and a sense of ownership and permanence. Where this infrastructure is lacking, there is a key role for statutory partners in helping to develop it.

Why is this hard?

Our research also investigated the barriers and challenges to more effective and widescale neighbourhood working. Across the sample some key shared barriers emerged, a number of which related directly to those areas that were identified as ‘making this work’:

- Funding. Several of the case studies were reliant on multiple or diverse funding streams. While diverse funding streams can be helpful in mitigating risks of funding suddenly ending from a single source, this also requires significant ongoing management, while wider fundraising efforts can distract from service delivery. Neighbourhood working often addresses wider determinants of health and aspects of health and wellbeing that may only realise benefits for statutory partners in a diffuse way or over a longer timeframe than current budgeting and planning rounds. A lack of flexibility in funding and a dependence on pilot approaches can also prevent interventions from adapting to neighbourhood needs or allocating resources towards the highest priority activities as these evolve over time. While funding made available to support health inequalities could be a source of support, this was not always easy to access at a neighbourhood level and was often non-recurrent, preventing building up a sustainable offer to local communities.

- The definition of a neighbourhood and communities. In most cases, local people will define neighbourhoods in ways that do not align with statutory services and vice versa. This does not have to be a barrier but can become one when local discussions become stuck at the definitional stage, and / or there is a lack of readiness to accept a degree of imperfection in coming to compromises around where and how to define boundaries. What is true of neighbourhoods as geographic units is even more complex in relation to the communities that live in and across them. Successful community-led interventions were ones that had been able to navigate these complexities with statutory partners without losing focus on the importance of ‘getting on and doing things’ with shared benefits for those involved.

- Reliance on a few leaders who ‘get it’. Successful case studies were able to build connections often due to the efforts of locally influential leaders who were willing to invest in neighbourhood working and community development. While this may be a necessary precondition to successful neighbourhood working in future, it creates issues both if individuals leave their current posts or are otherwise unable to continue the work, and for all of those areas where equivalent individuals are not yet identified or working in this way.

- Balancing immediate needs with longer term solutions. The priority around neighbourhood working, including the development of INTs within the NHS, relates to challenges that are impacting communities and the services that support them today. However, this can lead to a temptation to focus on short-term solutions and objectives, including those that address symptoms rather than causes. For most areas, there will be a need to construct a business case for investment that balances both short- and long-term opportunities with needs.

- Data and information sharing. Within our statutory partnerships it can be difficult or impossible to share data across different teams, organisations and systems. This has a direct impact on the ability to co-ordinate service delivery and to evaluate the impact of existing and new interventions. When this is extended to community-led initiatives, supported by VCSE organisations, the challenges are exacerbated. If statutory partners want to work in a more integrated way with VCSEs, communities and individuals, as information systems and governance evolve it will need to take into account the risks of both sharing and not sharing information outside of traditional structures and silos.

- Managing and responding to diverse and conflicting views. Diversity exists at all spatial levels but is often lost in the need to aggregate requirements and standardise approaches. Part of the power of neighbourhood working is the ability to recognise and respond to diverse needs, but to do so effectively there needs to be a recognition that even in a single street residents will have different cultures, beliefs and opinions on their needs and priorities. Reaching consensus can be a challenging process and neighbourhood-based working needs to be particularly mindful not to simply adopt the ‘loudest voices’ when making decisions that need to be genuinely participatory.

- Reliance on volunteers and high volunteer turnover. Many of the case studies rely on volunteers who provide energy, passion and dedication to the communities and neighbourhoods they support. However, this reliance can pose a risk as turnover among volunteers can be high, which can sever individual ties with residents and incur additional overheads in regularly having to onboard new volunteers. The availability of volunteer time was not found to be evenly distributed across the places we engaged, disadvantaging some neighbourhoods that have a smaller pool of volunteer time to draw upon. Overall, there is a balance to be struck between ‘professionalising’ neighbourhood working – potentially breaking the link with local people, the knowledge and different ways of thinking they bring – and being overly reliant on people who are trying to support their community but at the same time balancing many other professional and personal needs.

- Performance management and targets. The centralised approach of the NHS to performance management and output measures does not always lend itself to projects focused on wider determinants of health, health creation and prevention. Particularly where diverse sources of funding are being used by a single organisation, reporting requirements can become a barrier to progress. These activities are likely to realise benefits in a much longer timescale, perhaps years in the future, compared to more acute delivery. There were seen to be significant risks in heavy handed, overly frequent, or inappropriate monitoring that could stand in the way of or divert resources from encouraging participation and delivering on outcomes themselves. Attempting to fit local and hyper-local initiatives into broad national frameworks such as those for NHS performance management is likely to stymie the growth of effective joint working at a neighbourhood level. It could also inappropriately incentivise activity and funding, which if allowed to develop more organically around local needs would in time feed through in different and more positive ways into supporting overall system performance.

- Existing infrastructure. Community infrastructure is a critical starting point for neighbourhood working and this creates a challenge for neighbourhoods with low levels of existing infrastructure to build upon. In rural communities there were issues with sparse transport infrastructure, while in urban areas access to affordable, convenient and shared spaces to meet is increasingly limited. Overall, areas of high socio-economic deprivation tended to face more barriers in terms of historic underinvestment or lack of revenue support to create and sustain community assets, increasing the chances of such neighbourhoods being left behind.

Working together effectively

Across all examples, successful neighbourhood working was not delivered through discussion and agreements between senior leaders in a system. Although the failure of senior leaders to engage and support communities fully with neighbourhood working was seen as having the potential to undermine it.

Success meant working together in a way that enhanced the ability of partners to have a positive impact on the neighbourhoods in their area, and together achieve what each individual could not achieve alone.

Many of the non-statutory representatives in our research discussed the effect of a ‘power gradient’ between statutory and non-statutory partners, linked to control of funding and other decision-making levers as a barrier. Addressing this imbalance requires statutory organisations to step outside of their organisational comfort zones and embrace non-statutory groups as equal partners, sources of expertise in their needs and possessing valuable assets, including the ability to catalyse transformational change. It also requires the acknowledgement by statutory services of the different but equally significant power held at the neighbourhood level - the power that exists through connections, relationships and trust - and the power to undermine statutory interventions if people living in local communities do not feel those interventions have been designed with them in mind.

The connections between partners need to:

- be aligned on objective, purpose and outcomes

- be able to manage gaps, overlaps and resources as partners in change

- be focused on problem-solving for individuals and the neighbourhood as a whole

- share key information and resources (including training resources) in ways that reduce friction and address local needs, while respecting individual rights and privacies.

Impact measurement

There was a large variance observed in how impact was being measured and reported, evident in both the wider literature review and individual case studies. This diversity reflects varying resource, skills and focus associated with the models and interventions being evaluated.

- Most places can see and feel the difference they're making. They may have done an evaluation but the decision to engage in and continue to support joint neighbourhood working did not rest solely on formal evidence.

- Depending on the starting point, the impacts participants are interested in can vary significantly. A PCN-led model may have a principal goal of expanding the ability of the practices to meet patient needs, whereas a community group may focus on building social capital and community connectedness.

- Some interventions have been able to establish a link to reduction in demand for primary care and / or acute services in formal evaluative terms, but this level of evaluation is not available to most community-led schemes, which do not have access to the resources or data to undertake such detailed evaluation work.

- More statutory-led examples tend to have more quantitative metrics that are established at the outset of projects, often driven by requirements of local commissioners and the presence of teams and resources within partner organisations for monitoring and evaluation. However, while quantitative data can be a compelling driver of progress and future funding, the qualitative data being captured by local communities themselves can give as good, if not better, picture of the actual impact of the work on individuals within the neighbourhoods being supported.

Some neighbourhoods had partnered with, or planned to partner with, local academic institutions to support the evaluation of outcomes. This is a potentially powerful way of building evidence and learning locally and nationally, presenting benefits to both the evaluator and those being evaluated, as well as supporting the sharing of best practice outside of local areas.

Six principles to support neighbourhood working

Our research has suggested six principles to support neighbourhood working between communities and statutory services, building on existing enablers and aiming to reduce the barriers to future impact and spread.

Working together to take forward these principles requires stakeholders at all levels to make best use of their assets and capabilities, in enabling local health creation, addressing inequalities and empowering people to live happier, healthier and more fulfilling lives.

Recommendations

From the available evidence and case studies, we suggest that to enhance neighbourhood working there are three stages of foundational development. There are different roles that participants need to play at each stage and we have therefore grouped our recommendations by stage and stakeholder group.

These recommendations have been informed by what we have seen work well and what we have heard consistently getting in the way of progress. Alongside this, we have considered the different approaches to measuring impact observed so far.

All the recommendations are underpinned by the six principles for neighbourhood working, outlined in the previous section. However, it is important to note that these still only represent the first step in what, for many neighbourhoods, has been a multi-year or multi-decade journey. This journey is often not linear and as such these stages will often need to be progressed in parallel with each other, involving different stakeholders at different times.

Three stages of neighbourhood working

- Stage 1: Catalyse

The point at which neighbourhood working opportunities are first being identified and explored. - Stage 2: Nurture

The point at which neighbourhood working activities and interventions are being established and showing early promise. - Stage 3:Sustain

The point at which longer-term support, investment and structural changes may be needed to maintain impactful local initiatives and create space for new initiatives to emerge.

Three key stakeholder groups

- Neighbourhood: the people directly involved in neighbourhood working. This might include residents, community groups, schools, statutory services and VCSE organisations.

- System and place: leaders and decision-makers at a system and place level. Given the varying sizes and structures of the 42 ICSs in England, we have not separated place and system. Who leads and owns work for neighbourhood health will need to be locally determined but we expect integrated care partnerships and place-based partnerships to play key roles.

- National: policy and decision makers at a national level, including central government and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), national statutory bodies such as NHS England, national membership bodies, charities and other VCSE organisations.

Stage one: catalysing neighbourhood working

Neighbourhood

- Build a coalition of the willing. Work with residents, the local authority, the NHS, VCSE organisations, local businesses and other partners to map the assets, capabilities, current activities and needs in the neighbourhood, and identify where the gaps are.

- Recognise the need to engage beyond those already engaged in place and system working, including those communities at greatest risk, working through local intermediaries such as community and faith groups as appropriate.

- Work collaboratively to develop a collective approach that balances community and statutory priorities, giving equal weight to each.

- Establish relationships of trust from the outset, building an understanding of the motivations of all involved and demonstrating how proposals reflect the shared values of the neighbourhood and its partners.

- Identify existing local data to supplement standard national data sets, combining this with community insight.

- Agree and establish clear metrics and processes for tracking progress and impact at the outset of neighbourhood work. These do not have to be fixed or complicated and are likely to evolve over time. The purpose is to start to build an evidence base for new ways of working and better understand what does and does not have the impact that you are looking to achieve. What is important is that these reflect not just what is currently measured and managed by services and systems but are genuinely co-developed with communities themselves.

- Prioritise identifying someone to act as a point of co-ordination able to take the lead on bringing people together while willing and able to work in a new paradigm, with and not simply just within neighbourhoods and communities.

- Identify those professionals, clinicians or managers who will work alongside community groups to support and advocate for them while bringing an understanding of the existing health system, helping to navigate challenges and identify opportunities. Consider whether there is someone already in the locality with the right skills and a facilitative approach to take this on, or if not, how to support people to do this including in key areas such as relationship building.

- Find a space where people can come together. Make it as approachable and accessible as possible. People may avoid places that feel too much part of statutory systems and structures. Local venues, such as a pop-up space in an empty shop, or a local café. If possible, it is important to provide refreshments as well as comfortable and informal seating.

System and place

- Think neighbourhood. Consider how working differently with communities to enable neighbourhood working will impact on current models of planning, delivery and assurance. Allowing neighbourhoods to define their own boundaries might feel simple but is far away from many current discussions around how different statutory footprints could be better aligned. Avoiding the temptation to duplicate or systematise initiatives that are already working at a neighbourhood level is hard but offering support to those leading these initiatives to sustain what they are doing and, where appropriate, grow their reach and impact, is critical.

- INTs and related approaches to working with communities will need to align to, but are not the same thing as, community-led development. The more that communities are involved in INT development the more likely such policy-led agendas are to succeed. But, the evidence suggests there will likely be a need in most places for spaces outside of the formal, integrated structures and delivery mechanisms to enable community innovation and empowerment to thrive.

- Community asset mapping provides one approach to understanding social networks at a neighbourhood level. Identifying individuals and influencers is part of this process but is not a substitute for a broad-based approach to developing community power.

- Active listening is essential to understand the support needed to enable genuine partnership working in taking forward relationships, whether this is small amounts of initial funding investment, facilitation of different types of conversations, or more fundamental shifts in how current engagement within neighbourhoods is structured or delivered.

- Recognise that there are inherent power imbalances between statutory services and communities that can impact on neighbourhood working, and that it is the role of those who hold the most power to proactively address these. Even at this foundational stage there is a need to understand the role of communities in decision-making at place and system levels, if the benefits of neighbourhood working are to be scaled.

- Align existing and new statutory services, and particularly primary and community care resources, around neighbourhood priorities. This includes workforce strategies that reflect requirements for neighbourhood working and that encourage providers to include neighbourhood team working in job descriptions and job plans where possible, as well as approaches to areas such as estates that understand and respond to the gaps that have emerged in local community infrastructure.

- Agree on proportionate approaches to governance and reporting on progress and outcomes without creating administrative barriers at the neighbourhood level. This can be supported by creating a hub at system or place level capable of sharing best practice and supporting new forms of value measurement, including understanding the impact on social capital.

Stage two: nurturing neighbourhood working

Neighbourhood

- Continue to develop a shared understanding of the drivers and priorities of communities and services operating within identified neighbourhoods.

- Build on trust and understanding, including through sharing progress against shared goals and understanding the roles that each partner is playing, as well as working together to strengthen application of shared values to daily practice and overcome remaining barriers to change.

- Continue to adapt and evolve, being unafraid of letting go of things that are not working to create space for new ideas to emerge. This includes understanding how widening the initial partnership and community empowerment creates additional opportunities to broaden and deepen impact.

- Systemise governance and oversight structures that involve people from across the local system to support a sense of shared ownership and accountability for the success and ongoing sustainability of neighbourhood working initiatives.

- Understand implications for voluntary and community sector capacity as developments scale, including the need to provide additional resources and capacity to balance existing and new demands.

System and place

- Make connections between the people leading change and support to capture and learn from this, for example local universities and Health Innovation Networks.

- Understand opportunities to invest in individuals within communities to equip people with the skills and capabilities to help plan, develop and evaluate the impact of joint working with statutory partners. Recognise that there will be an equal if not greater need to support professionals to work differently with local communities in this context.

- Continue to share best practice and evidenced approaches from elsewhere, Including building on lessons from other sectors in strengthening community engagement, providing coaching and mentoring, and enabling peer support.

- Identify funding and support to build relationships and sustain local trust. From a statutory perspective, this could include funding through intermediary organisations or alliance contracting to enable shared management of activity and risk. Creating space and flexibility within existing funding arrangements will be critical to ensure that local neighbourhood partnerships can respond to and invest in local assets and needs.

- Recognise that this is a major cultural change, requiring support and investment in areas such as change management, organisational development, relationship and community development, volunteering and project management.

- Take action to ensure neighbourhoods have, can access, and make effective us of community infrastructure. Having a physical place to be is a key enabler of joint neighbourhood working. Equally this will need new relationships between organisations and communities to create an environment to foster change.

- Ensure effective support. Neighbourhood partnerships often do not have the resources to be able to easily scale and may need help with a range of support functions including recruitment, DBS checks, sharing standard policies (such as safeguarding) governance processes and structures. Statutory partners can help support communities through this if they can engage at the right time and in the right way.

Stage three: sustaining neighbourhood working

Neighbourhood

- Invest in the local workforce alongside volunteering roles, as neighbourhood working continues to grow and develop.

- Recognise that an overreliance on volunteers or the goodwill of individuals can put the sustainability of neighbourhood working at risk. Consider how best to invest in building up community capacity and resilience, working around existing shared values and goals.

- Continue to monitor, report and evaluate activities at the neighbourhood level, sharing this learning with partners both within and outside of the local neighbourhood, building credibility and sustainability. Recognise that this is an opportunity not just to reflect existing ways of measuring success but to understand impact from the community perspective too.

System and place

- For real lasting change to take place, leaders of that change must be prepared to change themselves and work with themselves as instruments of change in action. This means investing time to examine their own beliefs, strategies, behaviours and what is needed to support the next stage of development.

- Consider developing communities of practice to support ongoing dialogue, facilitate shared learning, enable joint problem-solving and the identification of further opportunities.

- Work with communities to continue to deepen understanding of assets and needs within neighbourhoods and how this can be reflected in better place and system working.

- Success in addressing initial challenges will only be sustained if there is a shared commitment to going beyond addressing individual issues in specific localities to ensuring that relationships and values continue to be strengthened in each interaction between statutory partners, professionals and communities. This will require ongoing investment in statutory and VCSE-based teams.

- Consider how knowledge, resources and people can be enabled to ‘flow’ within systems in the context of evolving needs, developing policies and processes to support enhanced capacity, skills and shared learning across neighbourhoods and priorities.

What does this mean for the national level?

The role of national bodies, such as NHS England, DHSC and HM Treasury, as well as national charities and organisations, is to create the conditions and permission for change and to inspire the advancement of neighbourhood working as a core part of delivering on a broad set of policy goals.

National frameworks and policy documents such as the Fuller stocktake provide valuable guidance and validation for the work being done at the local level. However, the hyper-local nature of these initiatives and their adaptation to local contexts does not lend itself to a standardised or directive model of change. This means taking a high-trust and light-touch approach to supporting and funding change and monitoring progress.

In addition to the practical steps at the neighbourhood and system and place level set out in the previous section, we have also identified specific policy recommendations at the national level which would facilitate good neighbourhood working to develop.

- NHS England and the DHSC need to embed these ideas in the new ten-year plan for the NHS. The shift to a community-first approach should be recognised as one of the biggest change programmes in the statutory sector’s history and supported as such. The ten-year engagement planning and health mission delivery board should have a specific focus on greater devolution as part of NHS reform. prioritising new models that strengthen community-based health, unlock community assets and strengthen local decision-making. However, they need to accept that the models have to be developed locally and resist the temptation to develop national templates and exemplars or to reinvent the project management approach used for the integrated care vanguard programme.

- Much more devolution of decision-making and less central direction in how NHS England operates is required. This is needed to create the space and energy for neighbourhood working to flourish.

- NHS England should make changes to create a funding regime that is more supportive of this new settlement:

- Each ICS should be encouraged and empowered to use flexibility within the existing NHS Payment Scheme to support local innovation and experimentation

- Adapt the NHS Payment Scheme in 2026 to include outcomes-based payments. This will enable ICSs to create the better financial incentives to support a leftward shift in services and resources towards primary and community care.

- Implement the Hewitt review’s recommendations related to how non-recurrent funding is managed, with fewer stipulations on how it is used locally, and reducing the number of national targets, focusing more on outcomes than activity.

- DHSC and NHS England should shift the NHS to multi-year funding and planning cycles aligned with local authorities, to enable long-term planning and accelerate integration in budget management, planning and delivery between health and local government. HM Treasury should help to facilitate this change.

- DHSC and the Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government should review Better Care Fund and Section 75 arrangements and consider how they can make pooling budgets easier, including by reducing the reporting and governance requirements associated with them.

- NHSE and DHSC should revise the GP contract to create greater devolved accountability, strengthening primary care’s capacity to play a leading role in neighbourhood health models. Reviewing the Carr-Hill formula will be key to strengthening investment in some of the most deprived communities.

- NHS England should ensure that evidenced approaches are documented and available for system, place and neighbourhood partners to draw from as they develop their local approaches. These should particularly include examples that combine community and statutory leadership.

- Cross-government action is required to promote this agenda. Government should convene cross-departmental work with an alliance of organisations at national level that are leading or driving change in neighbourhood health across health, local authority, business, communities and voluntary sector to inform future policy planning. This should include the development of more routes for schemes to obtain seed-corn funding to promote local initiatives.

Conclusion

We live, grow, and develop in neighbourhoods.

The factors that enable us to thrive at every stage of our lives are grounded in our communities, where we learn, where we work and where we live. In this report we have shared recommendations around maximising the opportunities and the value of communities and statutory partners working together differently, in a neighbourhood context.

When the organisations working in our neighbourhoods align their actions around shared goals, and do so in partnership with the community, we are more likely to succeed, economically, socially and in enjoying better physical and mental health. For organisations in the statutory sector, developing a deep understanding of, and partnership with, neighbourhoods has benefits in both the reach and the impact of the services they can offer, and in the outcomes they can enable.

Over the long term, it is possible to see a real and positive impact on the effectiveness of statutory services, delivering better health and wellbeing outcomes for individuals and at the same time delivering better value for money for taxpayers. Even in the short term, there are already examples of economic and social benefits and not least of transformed lives in some of our most disadvantaged communities.

Developing and maintaining impactful neighbourhood working requires a different approach to change. Partners and collaborators need to develop an adaptive model that responds to learning and emerging needs, is rooted in a deep understanding of the local context, is willing to take risks and is not afraid to cede the initiative and leadership to others.