Key points

While a theoretical understanding of the links between health and wealth is increasingly recognised, the practical elements of what makes it work on the ground are less evidenced. This paper shines a light on these elements, showcasing tangible principles that work.

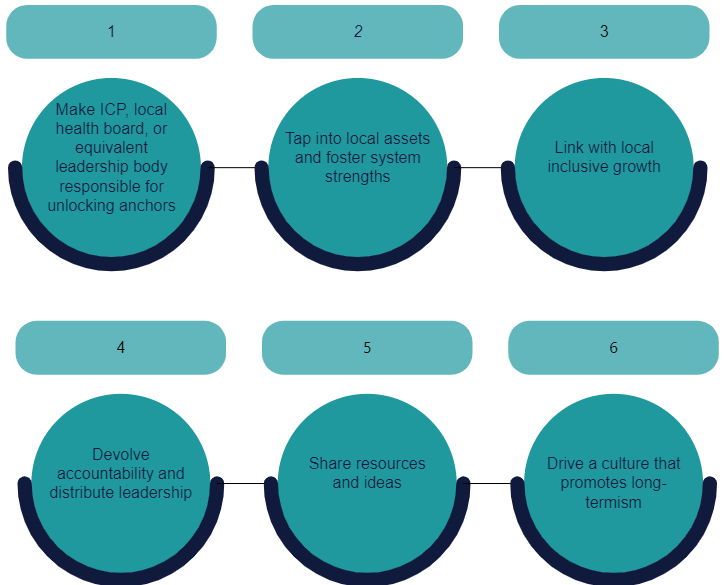

Based on engagement with five local areas in England and Wales, it puts forward a set principles that have proven to aid successful social and economic development: making the integrated care partnership, health board or equivalent leadership body the vehicle to unlocking the anchor system; looking inward and recognising the assets systems already have at the ready; linking with local inclusive growth strategies; devolving accountability; sharing resources across partners; and leading the cultural shift necessary to generate more long-termist thinking.

Each of the places we worked with provided a case study to illustrate what the principles look like in practice, surfacing the different ways in which this mission can be successfully progressed, regardless of the system’s maturity and experience in this area.

For many of these principles to work in practice, the centre will need to do its part to allow leaders to fully harness the autonomy that devolution requires, while ensuring that the necessary resources to realise social and economic development are provided in a sustainable and robust fashion.

Foreword

With the dawn of a new UK government, we have seen messages laden with an explicit understanding that the health of the nation and the health of the economy are inextricably linked. This overt understanding is not only promising, but it allows us to shift a portion of our energy from illustrating these relationships to implementing them on the ground.

I have the unique privilege to serve as a member of the Institute for Public Policy Research’s (IPPR) commission on Health and Prosperity, and have seen first-hand that, through partnership, the NHS Confederation and IPPR have uncovered new ways to test our hypotheses, ask new questions and develop tools to support local and national leaders as they advance on the journey towards social and economic development. Collectively, we have illustrated that better health has substantial value and responds to the major economic challenges facing Britain today.

As this report makes clear, the insights that leaders gain as they embark on their respective social and economic development journeys can be shared across borders. It is my hope that as the government places this agenda at the forefront of its policies surrounding health and growth, the NHS’s power as an anchor institution progresses from theory to practice, and that leaders are given the space, budget, autonomy and time to drive their respective health and growth agendas. It is evident that leaders have a will to do this. Now is the centre’s time to give them a way.

Matthew Taylor

Chief Executive

NHS Confederation

Background

The Commission on Health and Prosperity, a landmark initiative led by the IPPR, has published a range of evidence on the interaction between health and prosperity. In April 2023, it released new evidence showing that - all else being equal - the onset of a health condition caused people to lose thousands of pounds of earned income, increased the risk of exiting employment profoundly and undermined both job satisfaction and productivity.

Since then, the commission has shown how poor health and economic outcomes cluster in some parts of the country over others, how poor health undermines public finances, and the huge cost of population sickness to UK businesses. In short, it has conclusively demonstrated that better population health is the UK’s clearest, untapped path to prosperity.

Better population health is the UK’s clearest, untapped path to prosperity

To show the size of the economic prize for place-based working, new analysis for this report explored variation in economic inactivity due to sickness between the healthiest and least healthy parts of the country. Looking at Britain, and using a mix of healthy life expectancy and Labour Force Survey data, we find that:

- the local authority healthy life expectancy gap between the healthiest and least healthy local authorities is now over 20 years for both men and women

- less healthy local authorities consistently have substantially higher economic inactivity due to sickness rates than the healthiest – for example, in the least healthy part of Britain, Blackpool, healthy life expectancy is under 55 years, 15 per cent of women are inactive due to sickness, and 13 per cent of men are inactive due to sickness; in Wokingham, one of the healthiest places in Britain, healthy life expectancy is above 70 and the economic inactivity due to sickness rate is around 2 per cent for both men and women

- if the rate of economic inactivity due to sickness was as low in just the 10 per cent least healthy local authorities as in the 10 per cent healthiest authorities, we would expect more than 100,000 extra people to be in work. This would include around 60,000 men and 40,000 women. Addressing healthy life inequalities between places is key to achieving this.

While both poor population health and rising economic inactivity is often seen as a national problem, this shows it is actually highly localised, making targeted, place-level system working a key part of the solution. Getting it right could mean higher tax receipts, higher growth and a fairer country.

In parallel, the NHS Confederation’s Health Economic Partnerships team has engaged with integrated care systems (ICSs) across England to aid in the understanding of their ‘fourth purpose’ of supporting social and economic development and illustrate the variety of ways that it can work in practice. Shared in these pursuits is a will to explore how health and growth agendas are combined in places and to understand how they can be used to develop a bold, new and implementable reform proposition for building collaborative, healthy and prosperous places.

We have developed practical tools to drive social and economic development, quantified the return on investment (ROI) of further spend in the NHS and across various care settings, and we have engaged with leaders to explore what social and economic development is, why it matters to the NHS and how ICSs can develop more productive systems.

Supporting a national conversation while delivering missions locally

While leaders across the country have grown increasingly aware of the intrinsic links between health and prosperity, recent history has illustrated a trend of decline, with populations growing sicker and economies backsliding. Since 2019, healthy life expectancy has dropped and incidence of major conditions like cancer and dementia has risen. Since 2020, economic inactivity has risen by 900,000 people – 85 per cent of this increase is due to those who are long-term sick. This will mean lower growth and tax receipts, and is indicative of how important better health is in creating the growth that is the central focus of a new government.

Several bodies of work undertaken by both the NHS Confederation and IPPR Commission on Health and Prosperity, including From Safety Net To Springboard and Healthy Places, Prosperous Lives have linked sickness to the UK’s stagnant earnings, to a weaker labour market, to lower growth and to lower productivity. These findings underscore the message at the heart of social and economic development – that sinking health outcomes do not just cost lives, but livelihoods and economic security too.

The delivery of missions will need to be led outside of central government

The new UK government has committed to mission-led government. It has set out five missions: on growth, opportunity, clean energy, crime and health. Missions work best when they go beyond setting targets. As Mariana Mazzucato, professor in the economics of innovation and public value at UCL, and other leading economists and academics have recently argued, they should also be thought of as ‘systematic policy instrument’ – that is, as an architecture for delivery. One implication of this approach is that the delivery of missions will need to be led outside of central government. Missions do not lend themselves to top-down delivery and command and control government architecture (an approach used by the last UK Labour governments).

About this report

To that end, this report can be read as a first provocation on how integrated care systems (ICSs) and local health boards can take the lead on health missions (and connect that health mission to both growth and opportunity missions). Ideas in this paper are relevant both to how ICSs can design and adapt their own missions, and how they can take an autonomous lead on delivering healthier, more prosperous places and lives.

By working together, the IPPR and the NHS Confederation have been able to delve further into national dialogues as they relate to this agenda and simultaneously support local practice. In this piece, we take this conversation further by showcasing meaningful and practical ideas for change throughout the country.

The principles can be drawn upon to support social and economic development

While health is devolved across the UK, there are commonalities throughout the nation that resoundingly illustrate the contribution the health sector can make to increasing prosperity. By working with a small selection of health and care leaders in England and Wales over the course of 2023, the NHS Confederation and IPPR have co-produced a set of guiding principles to align health with prosperity.

These principles can be drawn upon by health system leaders and governments across the four nations to support social and economic development. We want to demonstrate the full extent of value that the NHS already provides, as well as to help it unlock its broader potential.

Methodology: Defining principles of social and economic development

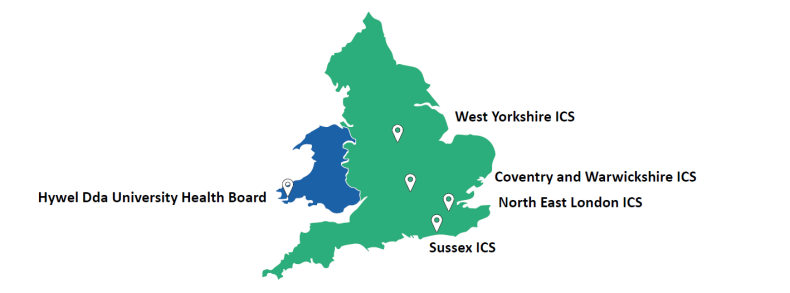

To look across borders in relation to this purpose, we invited ICSs and one Welsh local health board that embodied different demographics, institutions and geographies to work with us: Coventry and Warwickshire ICS, Hywel Dda University Health Board (HDUHB), North East London ICS, Sussex ICS, and West Yorkshire ICS.

Figure 1: Who we worked with

Despite their different structures and geographic spread (see Appendix 1 for more), local health boards and ICSs similarly depend on collaboration and focus on places and local populations as the driving forces for improvement. Given their explicit shared purposes of improving health outcomes and reducing inequalities alongside their makeup and design, local health boards in Wales and integrated care systems in England are the ideal bodies to take on the health and prosperity agenda.

During our discussions, each group of leaders across England and Wales provided unique perspectives and understandings surrounding health and prosperity, including how they are linked conceptually and how their intrinsic relationship plays out in local places. The resulting diversity in discussions supported a collective development of a framework built for and accessible by all as they tap into the links between health and wealth.

To understand each local area’s overarching view on this purpose, we prompted discussions that focused on six key themes:

- governance

- direct levers

- partners

- long-termism

- assets

- accountability.

These themes represent some of the mechanisms that ICSs, local health boards or other bodies could tap into while exploring health and prosperity links more autonomously and ambitiously, with no predisposition for which of them could prove to be more or less useful.

In regard to governance, we wanted to gauge leaders’ understanding of what it means to be an anchor system and how a collective ‘anchor vision’ could best be created locally. We also enquired about partners, particularly related to who the ‘right’ partners were deemed to be, which party should be held responsible for cultivating and sustaining a given partnership, and the appropriate forums through which partners can collaborate. Surrounding the direct levers for prosperity, we were interested to learn more about the tools – such as procurement, employment, location and innovation – systems have at the ready to shape the prosperity of their place.

We also probed systems’ ability to build assets that do not already exist in a given place, and what that looks like in practice. We discussed long-termism, with a specific focus on how systems manage long-term ambitions with competing short-term pressures. Finally, we talked about accountability and challenged the notion that system-led approaches to health are accountable to ministers or NHS bodies and instead raised questions around the role of the public, including patients, service users and staff.

Throughout our discussions with the five local areas, we supported and facilitated ICS and health board leaders as they themselves grappled with the challenges in developing approaches to health and prosperity. Together, we unpacked the successes and challenges in each system’s capability to both understand and capitalise upon the links between health and prosperity.

Despite the uniqueness of the five local areas included in this study, several themes echoed throughout each conversation. The six principles outlined below were therefore derived from supporting systems with their local discussions and practice and were inherently co-created from the bottom up.

Six principles for advancing social and economic development

1. Make the ICP or equivalent leadership body the key to unlocking the anchor system

While there is a significant and widespread willingness to work together to align health and prosperity and to deliver on social and economic development, there remain challenges in how we view and approach cross-sector system working. Priorities are still seen through an organisational anchor lens, with isolated actions often being led by different partners and for different reasons, all while being largely focused on the shared populations. Scale, long-termism and a broader approach to health, not healthcare, are all vital when it comes to social and economic development.

In England, the integrated care partnership (ICP) is seen by many as the right body to bridge these gaps and ensure the right partners across a system are at the table and aligned in their vision, mission and behaviours. Across Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, the equivalent leadership body could be a local health board or alternative sub-national partnership.

Focused on the strategic needs of tomorrow and with a broad, outwards facing membership, ICPs and equivalent leadership bodies outside of England are what truly stand out as different about the UK Government 2022 health and care reforms. One of their core strengths is an ability to take a holistic view across the varied, critical challenges facing our places and to align individual anchor strategies in ways that maximise their inherent value. Nonetheless, unlocking the potential of ICPs will require both resource and purpose – pushing them from being groups of important leaders to important groups of leaders who are able to collectively convene, lead and implement change.

“The ICP role is critical. We need to ensure that it has the independence and clout that it needs to truly lead this work.” ICP Chair

“We repositioned ourselves to be as much a vehicle that represents the community as one which is a local expression of government. The health board wants to recognise the duty it has to the community it serves – being owned by the community – as much as being government owned.”

Case study: Introducing recycling services for absorbent hygiene products waste

What the board faced

Hywel Dda University Health Board used to send approximately 160 tonnes of absorbent hygiene product waste to deep landfill sites each year. The primary supplier of these products was a multinational organisation that offered little environmental benefit or social value for the health board.

What the board did

The heath board has since partnered with a local company based in Ammanford that employs local people based within the health board boundary. The waste is 100 per cent recycled, and the new contract has generated a £150,000 savings over the course of four years.

Leading up to a formal partnership, the organisation was asked to demonstrate how it would deliver social value through the life of the contract, using scored questions. The purpose of the questions was to allow the organisation an opportunity to demonstrate its commitment to support the health board in meeting its obligations under the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (“WBFG”): strengthening local supply chains in Wales and reducing carbon to support the NHS reach the Welsh Government target of becoming net zero carbon by 2030.

Results and benefits

Since partnering in 2015, the organisation has helped the health board to divert over 50,000 tonnes of disposable baby nappies and incontinence waste from landfills, saving a significant quantity of carbon emissions. Through treatment and recycling processes, 100 per cent of the products will be fully diverted from landfill and repurposed into new products such as road asphalt and fibreboard, reducing the need for materials from scratch and carbon emissions to produce them. Recycling performance will continue to be monitored and reported back to the health board in monthly waste reports.

2. Start with what’s strong, not what’s wrong, building on local assets

Conversations too often start with what is missing or needed, as opposed to what tools places already have and which can be leveraged. Place is a powerful and real concept that resonates, and local leaders are best placed to understand the range and versatility of assets available and how they can be most effectively employed. This mantra of ‘start with what’s strong, not wrong’ can help shift mindsets away from the immediate challenges facing individual organisations and sectors and towards a more common view of what binds and supports communities, including the pride local people have in their place and the reasons for it.

The fourth purpose of an ICS is an agenda that is inherently bottom up. The approaches taken to advance social and economic development, and the distribution and scale of public and private assets, will vary wildly across and within urban, rural and coastal economies. Starting with a mapping of what communities have access to, where they go and who they trust, will improve not only leaders’ understanding of their priorities but importantly how they can best deploy the collective resources they have to meet them. A key part of realising this is the intentionality to support, resource or move those assets that are seen as most transformational, and to understand who is best placed to lead.

However, there may be a role for national government in ensuring all places have more and more consistent strengths. IPPR North analysis shows that the equivalent of £15 billion local government owned assets have been sold in the last 15 years, while evidence suggests that more deprived parts of the country – where poor health and low opportunity cluster – have less green space; fewer community assets like pools, libraries and youth centres; and have lost preventative early years infrastructure like Sure Start. The centre could support strength-based work by ICSs through active investment in and development of existing strengths.

“We repositioned ourselves from an expression of government locally to a vehicle that represents the community. This was a significant shift in our thinking.” ICB Non-Executive Director

“The health board has been set up as a population health system – we already have many of the levers we need.” Executive Director

Case study: Risk prediction and prevention in high-risk cardiovascular disease patients in Wales

What the system faced

There is significant need to improve cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor management across the Welsh population. However, there is also variation in the quality of care, with inconsistent adoption of evidence-based guidelines, resulting in gaps in treatment and outcomes.

CVD encompasses a range of conditions that affect the heart, blood vessels or both, including angina, heart attack and stroke. The most common of these problems is atherosclerosis (a build-up of deposits of fat and cholesterol inside an artery, known as plaques, causing it to narrow and harden resulting in restricting blood flow) with acute events, such as heart attacks, caused by clots forming on these plaques.

What the system did

The system embarked on a project to leverage the existing data and informatics ecosystem (SAIL database) to identify patient cohorts at high risk of future disease based on phenotype and potentially genetics as a future approach.

Results and benefits

This type of partnership with the health system to test interventions in specific selected patient cohorts has helped to reduce the treatment gap and improve outcomes, ensuring all high-risk cardiovascular patients can be identified and then seen by the right person, in the right setting, at the right time, avoiding hundreds of CVD events.

This initiative has demonstrated improved outcomes because of a comprehensive approach to risk prediction and prevention, all while using a tool that the health board already had at the ready.

3. Link with local inclusive growth strategies

Through the NHS as an anchor concept, the health service has gained a much greater understanding of the range of direct levers at its control that can support local economies. Whether through recruitment, procurement, estates management, or research and development, the health and care sector innately possesses a myriad of methods to overtly stimulate economic growth in its vicinity. Two of the key challenges for many in approaching this agenda include knowing where to start and understanding which of these levers would add meaningful value to the local context.

At the heart of answering this question lies the increasingly clear read-across between population health and inclusive growth. The latter is an approach to economic development that targets actions and initiatives that tackle inequalities, including health inequalities. If we understand the links between population health and inclusive growth, we instinctively understand that these are topics that ought to be embedded in all strategies and fall under every leader’s purview.

This is very much a two-way street. As well as guiding the economic power of the NHS, this approach will also involve seeding health into local conversations surrounding issues such as jobs, housing, skills, transport and climate change. The local growth agenda is rapidly evolving as the UK Government pushes on with English devolution and ICSs need to understand where responsibility for growth sits, who is making decisions, and how to best influence them. It is vital that health, and thus health leaders, play an active role in Labour’s proposals for a new statutory requirement for local growth plans.

“System working can be difficult when health is viewed in a silo and not as part of a wider network including education, economic growth, innovation, transport, jobs and housing, for example.” ICB Director of Finance

Case study: Connecting communities with health and care careers

What the system faced

Leeds Anchor Network, established in 2018, brings together 13 of the largest organisations in Leeds – including the council, NHS trusts, universities and colleges, regional utility firms and large culture organisations – to increase their collective impact towards delivering inclusive growth.

Together, these organisations employ over 58,000 people, including 2,000 apprentices, and spent over £820 million in the Leeds economy and £1 billion in West Yorkshire 2022/2023. They have extensive reach to the city’s communities through their service delivery, and, with large estates and operations, have considerable potential to reduce their environmental impact.

What the system did

The council commissioned three locally rooted community anchor organisations in areas of the city with high levels of deprivation (Seacroft, Harehills and Armley) to understand local residents’ skills and abilities, alongside perceptions of the economic opportunities available to them.

This activity evidenced the underused skills in communities and what is important to people in terms of work, training and volunteering. For example, the importance of meaningful work as well as good pay; and that recruitment processes often feel impersonal and too fast-paced. Barriers to employment included digital skills and access, confidence, caring responsibilities, and opportunities not being advertised through local networks. There was a high level of interest in this subject and some groups have independently decided to continue to meet around this theme.

The council and local third sector are now progressing the next phase of this work, to bring representatives from Leeds Anchor Network together with local community members to co-develop solutions and small-scale pilots in response to the themes from the listening exercise. This includes looking at how they can make their existing vacancies easier to access, remove barriers to employment and within recruitment processes, as well as promote relatable role models and demonstrate visible career routes for people from disadvantaged areas of the city.

Building on a successful pilot approach developed in Lincoln Green to recruit local people to vacancies at St James’ Hospital, the Leeds Health and Care Academy –the city's partnership to develop and strengthen the health and social care workforce – Leeds City Council Employment & Skills, Leeds City College, and Community Learning Partnerships have developed and delivered a ‘flipped recruitment’ approach. This approach turns traditional recruitment methods on their heads to make careers in health and social care more accessible to people in communities facing disadvantage.

Results and benefits

The programme is widening life chances while also improving staff recruitment and retention in the sector through addressing the root causes of the barriers that people face. Up to March 2024, 203 people, of whom 131 (65 per cent) reside within a priority ward, have been supported to improve skills in maths and / or English to help them to progress into future employability programmes to secure a role. 192 people have been supported into hard-to-fill priority roles, of which 58 per cent were previously unemployed. 79 per cent of people supported are from an ethnically diverse background, and the programme has a 96 per cent retention rate after 12 months (April 2023 to March 2024).

4. Devolve accountability and distribute leadership

One of the key strengths of the 42 statutory integrated care systems in England and the seven local health boards in Wales is an increased level of autonomy. This is particularly the case regarding the fourth ICS purpose, which has not been centrally defined by NHS England, neither in scope nor in measures. Similarly, the Welsh Government Economic Action Plan (EAP) has set the direction for a broader and more balanced approach to economic development, with a shift towards a focus on place and making communities stronger and more resilient while tackling inequality. With this increasing autonomy comes real opportunity to think anew, although it will ask leaders to be braver in how they use collective power to really change the way in which our organisations operate. This transition will involve both devolving accountability downwards and then distributing it outwards.

Place is vital in this agenda and devolution should empower local leaders. Addressing social and economic development might, for example, involve starting with a much more radical approach in the most deprived areas of the system footprint. What can the system do to allocate particular attention and support to these places, acknowledging their distinctiveness, trusting and empowering local leaders from across sectors, increasing the collective risk appetites, and allowing people to do what decentralisation and devolution have given us the power to do? Distributed leadership is important here, given the breadth of levers that will need to be pulled, in varied order and effect. Only increased agency will unlock the complementarity of systems.

Devolving power might benefit from the centre reconsidering its control architecture. Despite rhetoric on subsidiarity, local systems are still subject to a proliferation of targets. In turn, those targets tend to be focused on acute rather than preventative outcomes, constricting change. In line with the Hewitt review, a smaller set of targets may be beneficial in creating space for change.

The IPPR Commission on Health and Prosperity has previously called for targets to be reduced into a clearer, more outcome-driven central mission – for example, three broad targets for ICSs to deliver on healthy life expectancy, inequality reduction and economic development.

“The message to government needs to be ‘don’t box us in via a national agenda and targets that don’t make sense locally. Work with us and through us’”. ICP Chair

“The Well-being of Future Generations Act (Wales) makes thinking long-term an imperative and gives national permission for the local focus.” Executive Director

Case study: Taking a whole-system approach to tackling health inequalities at a borough level

What the system faced

The COVID-19 pandemic brought into focus the health inequalities for the population of Crawley, one of the most culturally diverse communities in West Sussex.

What the system did

The Crawley Programme is an initiative that tailors services in Crawley to meet the needs of the population, with a particular focus on the needs of the most disadvantaged communities. The programme brings health, borough council, county council, voluntary sector and local communities together to understand the key issues affecting health and wellbeing and to redesign the range of services to address those issues.

The programme has worked with communities and leaders to develop tailored health resources for communities and translate them into 13 community languages. The system has targeted social media promotion in these languages, and additionally developed staff cultural awareness videos. The system has also implemented a diagnostic centre in Crawley, which has improved access to diagnostic services and reduced the travel time and expenses for our communities. The system has also liaised with the local bus company to improve bus services between the most deprived areas and the community hospital.

As part of the Crawley Programme, leaders have developed three-year service redesign proposals that tailor mental health services and maternity services ensuring a more local and integrated offer underpinned by the access guide. Emerging models in Crawley enable practices to configure their own capacity and workflow processes to ensure the patients who need it most receive continuity of care. The team is working together to understand how to better integrate health, borough council, county council and voluntary sector service offers around those with multiple needs, recognising that many services see the same people.

The priority service developments are working together to ensure integration where appropriate and are being informed by the findings of the accessibility framework. This framework helps to inform how assets can be leveraged more effectively to support integration and services closer to the communities that need them the most. The programme has been underpinned by robust data, clinical insights and a combination of general and targeted engagement, with priorities and development of innovative solutions driven by local leaders and relative need.

Results and benefits

Some of the achievements of the Crawley Programme to date include a more robust system-wide partner commitment to developing the models of care and enhanced understanding of service and community strengths, providing strong foundations on which the models can be further developed. Moreover, the programme has created increased capacity to support diagnostics, improving access to vital testing across the community alongside positive feedback from disadvantaged communities surrounding health resources and better access to services.

5. Share resources and ideas across partners

Many of the issues that are most important for the long-term social and economic development of a place are thorny, with responsibilities spanning across various sectors. Addressing homelessness, tackling food poverty and improving civic pride are all examples of cross-cutting challenges that require a common, shared focus among cross-sector place leaders if inequalities are to be narrowed. Leaders often talk about the need to work with local partners to share resources and ideas. But in practice, this often looks like expecting others to accede to their approach: projecting as opposed to learning. This approach will inevitably raise more challenges than solutions.

Delivering on social and economic development is primarily about doing something that individual organisations cannot do alone, and understanding this is critical to being humble, open and curious with partners. This is particularly the case when it comes to prioritisation, measurement and assessment. The most impactful things for a local place are likely not valued by national NHS leaders, and what NHS England values the most probably would not have the same impact in a local area. Leaders should have the confidence to determine what is best for their areas and to act accordingly; sharing, experimenting, challenging each other and evidencing upwards. This might mean starting new conversations, but it also might mean inviting local system partners to join existing discussions.

“There is some great system working going on across partners and sectors. We are in the early stages of a missions-based approach, but having this holistic vision of our place is helpful to understand how we can work best as a collective.” Local Authority Chief Executive

Case study: Designing and scaling up menopause virtual engagement events and virtual group consultations in North East London

What the system faced

As societal awareness of the menopause increases – what it is, how symptoms manifest, potential care pathways and treatment options – health systems and services have witnessed a corresponding increase in need for support. This rise in demand represents a national trend, with individuals in certain parts of the country face waiting times of more than a year to be referred for specialist menopause treatment on the NHS. As increasing numbers of people pursue help for the menopause, systems must take proactive measures to ensure that adequate care is provided.

What the system did

In City and Hackney, there is a well-established pilot of virtual engagement events (VEEs) and virtual group consultations (VGCs) for menopause care. The virtual engagement events provide general education and guidance for people going through menopause, and virtual group consultations provide direct virtual services to women offering self-referral to specialist menopause support, eliminating an intermediary referral in primary care and lifting pressure from the wider women’s health care pathway. Both models deliver low-risk and high-volume care through interactive, virtual events. In virtual group consultations, women receive a longer amount of time, typically 90 minutes, of tailored information around the menopause as well as one-to-one management of their own specific issues, including advice from a physiotherapist, counsellor and nutritionist as needed.

Results and benefits

Three years on, the City and Hackney VEE / VGC menopause support model has witnessed various successful achievements including through health outcomes, patient experience, and wider system benefits. North East London ICB has witnessed a reduction in primary care uptake as well as general and community gynaecology routine referrals.

Moreover, through surveys, the virtual model has proven to boost primary care satisfaction and patient confidence in self-managing menopause symptoms. To promote this model widely, beyond the ICB and for topics outside of the menopause, NHS England and Wellbeing of Women have commissioned work to spread learning through a toolkit and cost-benefit analysis of the care model.

6. Lead the cultural change necessary to focus on the long term

That the NHS can be short-termist in its thinking, decision-making and processes is not new, nor is it controversial. One of the great hopes of system working is that a collective, strategic focus on the needs of tomorrow can help navigate the health and care service through the operational weeds of today. As stated in a succession of reports, including the April 2023 independent review of ICSs led by Patricia Hewitt, in order for ICSs to change this pattern locally, cultural and systemic changes are necessary, as well as changes to national expectations, timelines and funding.

Many health systems are at the initial stages on the journey surrounding social and economic development. The ICS fourth purpose maturity matrix produced by Cathy Elliott, chair of West Yorkshire ICB, as part of the NHS Confederation’s report Unlocking the NHS’s Social and Economic Potential, is acting for many as a loose blueprint through which to assess the progress being made over a ten-year period as systems move from emerging to established to expanding. Keeping this matrix updated as both systems and the economic context changes is vital, but so is the political, technocratic and community leadership required to create the conditions and environment in which people can deliver.

The government can also help by embedding its own long-termism. ICS long-term working can be blown off course by what politicians see as burning priorities – which often revolve around waiting lists and emergency department performance, rather than the population health outcomes that take time to change and deliver prosperity. High turnover of health secretaries, short-termism in Treasury and the politicisation of the NHS are all challenges here. Providing long-term funding, space to experiment and political acknowledgement that real change takes time would be useful.

Elsewhere, the IPPR Commission on Health and Prosperity has suggested changes to the centre’s health policy process that could better embed long-termism in Westminster and Whitehall – including a longer-term healthy life expectancy mission, evaluation of budgets and fiscal events on that mission, and the creation of an equivalent of the Climate Change Committee to take and embed a long-term view.

“How can we talk about long-term outcomes when our budgets are set yearly? We need to challenge the context in which we are working to enable us to really move forward on this.” ICB Director of Strategy

Case study: Coventry and Warwickshire’s trauma vanguard project

What the system faced

In August 2021, Coventry and Warwickshire ICB was successful in its bid to become the NHS England West Midlands Vanguard for the Framework for Integrated Care. The Framework for Integrated Care is the NHS’s response to the Long Term Plan commitment to invest in additional services for children and young people (CYP) in the most complex situations locally who have been subjected to child exploitation and significant trauma(s).

This funding has enabled the ICB and partners to pilot work in partnership with young people to lead on designing the framework and offers a unique opportunity to assess the impact of this new way of working to achieve sustainable cultural and organisational change.

With the steer and direction from children and young people across Coventry and Warwickshire and effective models of co-production, the ICB was able to officially re-brand the project to Positive Directions.

The framework is built on three pillars:

- Assisting the system in its ambition to embed trauma-informed approaches for CYP across statutory and voluntary agencies.

- Piloting trauma-informed ‘Positive Directions’ service with practitioners co-located into Coventry and Warwickshire Children’s services, with occupational therapy support and speech and language therapy input into Coventry’s Youth Justice Service.

- Developing and embedding a social prescribing approach to connect CYP to their communities, to make positive friendship groups, try new activities and have fun.

The project’s ambitions include:

- Using a non-medical model of trauma-informed approaches, acknowledging the relationship between people's life experiences and the presentation of behaviours that could be misinterpreted as mental health difficulties, avoiding pathologizing or labelling children and young people’s behaviours.

- Recognising that behaviour when understood in the context of trauma is normal.

- Encouraging a CYP-led ‘think family’ model.

- Promoting a system-wide, strengths-based, youth-work led model supported by universal and enhanced social prescribing offers.

- Looking beyond the adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) framework, recognising that misapplication of ACE theory can be maladaptive and deficit-based.

- Viewing trauma through an intersectional lens, recognising that each experience is unique to the individual, and understanding what life is really like for the child and young person.

- Challenging victim blaming and shaming narratives in professional and community context.

Results and benefits

- 69 per cent overall improvement in mental health and wellbeing

- decrease in the number of CYPs entering or returning to care

- reduction in school exclusions/refusals and an increase of 59 per cent of children returning to school

- 51 per cent reduction in the number of incidents of serious youth violence linked to gang involvement/affiliation

- reduction in hospital admissions due to mental health crisis/self-injurious behaviour

- increased confidence of practitioners in being able to identify and respond to trauma

- reduction in the number of children and young people returning to custodial settings and increase in GP registration leaving secure estate

- decrease in the number of young people from refugee/asylum seeking families becoming gang affiliated and involved.

Conclusion: A framework for development, towards health and prosperity

This report gives systems and the centre a sense of what is needed to foster health and prosperity. Our framework is summarised below.

Figure 2: Our framework for system maturity towards health and prosperity

While the notion that health and prosperity are inextricably linked is increasingly understood and accepted, it takes leadership, partnership and a will to make it happen in practice. Whether leaders find themselves at a nascent or more developed phase in this journey, it is our hope that these six principles will guide any partnership body to advance social and economic development and provide part of a framework to building more healthy and prosperous places.

ICSs and local health boards play a pivotal role in bolstering the health mission, but also the growth and opportunity missions

For national policymakers, our framework begins to outline how missions can be delivered locally. As demonstrated throughout this paper, integrated care systems and local health boards play a pivotal role in bolstering the health mission, but also the growth and opportunity mission. Progress, however, cannot be achieved through an overly centralised approach. Rather, we need a plan to empower bodies like ICSs and local health boards as local delivery agents – able to adapt and tailor missions to their bespoke local contexts. Our framework would set the foundations for doing that as the new government begins its work.

Acknowledgements

This piece would not have been possible without the gracious time and honesty of leaders who invited us to join their existing board discussion forums. Sincere thanks to Coventry and Warwickshire ICS, Hywel Dda University Health Board (HDUHB), North East London ICS, Sussex ICS and West Yorkshire ICS for inviting us into the conversation, allowing us to ask complex questions, and providing candid feedback regarding what works and what needs to be done to make this mission a success.

Appendix 1: Understanding local health boards and integrated care systems

In Wales, the Welsh Government sets the strategic framework and formulates the health and social care policy which is to be implemented by NHS organisations and its partners when planning and delivering services for the people of Wales. The NHS in Wales delivers services through seven local health boards, three NHS trusts with an all-Wales focus, and two special health authorities. The local health boards are responsible for planning and securing the delivery of primary, community and secondary care services alongside specialist services for their areas. These services include dentistry, optometry, pharmacy and mental health services.

They are also responsible for delivering services in partnership, improving physical and mental health outcomes, promoting wellbeing, and reducing health inequalities across their respective populations. The local health boards work with local authority and wider partners through regional partnership boards, which were established to improve the wellbeing of the population while also bettering the delivery of health and care services. There are seven regional partnership boards covering the local health board footprint.

The local health boards also work with local authority and wider partners through public services boards (PSBs). PSBs were established to bring together local public service leaders to assess and address the wellbeing needs of their areas, as part of the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. The Act established a board for each of the 22 local authorities in Wales. However, PSBs have the opportunity to work together across local authorities and to merge, and there are now 13 PSBs covering the whole of Wales. The duties of the PSBs include assessing the state of economic, health, social, environmental and cultural wellbeing in their areas, known as the ‘wellbeing assessment’ and setting local objectives that are designed to maximise their contribution to Wales’ wellbeing goals and publishing a Wellbeing Plan.

The Welsh Government’s Foundational Economy in Health and Social Services 2021/22 Programme, published in November 2021, sets out how health and social care can maximise the impact they make to Wales as anchor institutions. The programme focuses on the three Ps:

- Procurement – how spend can be leveraged to benefit Welsh businesses and communities.

- People – how recruitment can employ people from the communities served, especially those further away from the labour market.

- Place – how the health and social care ‘footprint’ and estate can be managed to provide better access to services as well as benefit local communities, businesses and the third sector.

In England, statutory ICSs are made up of two key components: first, integrated care boards (ICBs), which are statutory bodies that are responsible for planning and funding most NHS services in the area, and second, integrated care partnerships (ICPs), which are statutory committees that bring together a broad set of system partners [including local government, the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector (VCSE), NHS organisations and others] to develop a health and care strategy for the area. Working through their ICB and ICP, ICSs have four key aims: improving outcomes in population health and health care, tackling inequalities in outcomes, experience and access, enhancing productivity and value for money, and helping the NHS to support broader social and economic development.